Anthony Burgess at the Movies: Tunes of Glory (dir. Ronald Neame, 1960)

-

Will Carr

- 27th November 2021

-

category

- Blog Posts

To mark the 50th anniversary of the first release of Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation of A Clockwork Orange, we present a weekly online series Anthony Burgess at the Movies in which we zoom in on Anthony Burgess’s interest in cinema.

What Burgess says: ‘Another film with a Scottish setting – totally authentic in its racial and social milieu – and unusual in that it deals with a phase of army life in which the clash of personalities within a regiment replaces the traditional theme of how that regiment confronts an enemy. The performances by Alec Guinness and John Mills are masterly, the décor is superb, and the grim story is altogether convincing. This is conceivably one of the ten best films ever made.’

Set in 1948, Tunes of Glory pits Major Jock Sinclair (Alec Guinness), acting colonel of a Scottish regiment, against his replacement, Colonel Basil Barrow (John Mills) in a battle for authority and respect. The setting is a gloomy castle in winter, in which the somewhat bored regiment is barracked with the men spending much of their time half-heartedly running around assault courses and drinking and dancing in the town. The end of the war has left the regiment without real purpose, and while Jock Sinclair led it with distinction into battle, he is considered unsuitable for peacetime by a faraway headquarters and is replaced by Basil Barrow.

Jock Sinclair is a hearty and boisterous figure whose large appetites and disregard for protocol are contrasted with Basil Barrow’s orderly asceticism, and much of the drama stems from the antagonism between the two. The routines and frustrations of army life provide a background against which their personalities are outlined, and a moment of unexpected violence by Sinclair and his subsequent court-martial by Barrow tests their characters as they try to respond. Ably supported by an ensemble cast including Susannah York, Dennis Price and Duncan Macrae, Alec Guinness’s performance was considered by him and by critics as being one of his finest, and he expertly presents a complex, dangerous, pathetic man who we never quite know what to make of; similarly, John Mills’s character avoids becoming a neurotic bore and is instead troubled, principled, vulnerable and uncompromising by turns. Both Guinness and Mills received BAFTA nominations, and Guinness won the best actor award at the Venice Film Festival. The screenplay by James Kennaway, adapted from his own novel, was nominated for an Academy Award.

Anthony Burgess was not alone in considering Tunes of Glory to be an exceptional film. Alfred Hitchcock thought it was ‘one of the finest films ever made’, and its reception by critics was very positive. Shot in fine colour, its setting and costumes complemented the acting and script, and the unobtrusive camerawork in mainly intimate domestic settings allowed the actors to portray a vivid range of emotions. Another feature of the film is its score by Malcolm Arnold, which provides the tunes of glory of the title: full of pipes and drums, it powerfully evokes the distant history and honour of the regiment even as it struggles to reconcile itself to a new peacetime world.

Burgess’s own experience in the army was in some respects not dissimilar to that presented in Tunes of Glory. Having completed his basic training at Eskbank, near Edinburgh in Scotland, he spent much of his military career in the Army Education Corps on Gibraltar. This was a long way from the fighting and his main antagonists were the officers in charge, Major W.P. Meldrum and Warrant Officer Crump, as well as his recalcitrant students drawn from the ranks. Burgess’s memoirs and his novel set in wartime Gibraltar, A Vision of Battlements, show his keen observations of the absurdity of army rules and traditions, its occasional humour and camaraderie, its boredom and pedantry, and in particular the rich cast of characters that it allows. His battle with Major Meldrum in particular, who refused Burgess emergency leave to return to England as his wife Lynne had been seriously assaulted, has an echo in the clashes of personalities depicted in Tunes of Glory. It is not hard to see why the film might have spoken to him.

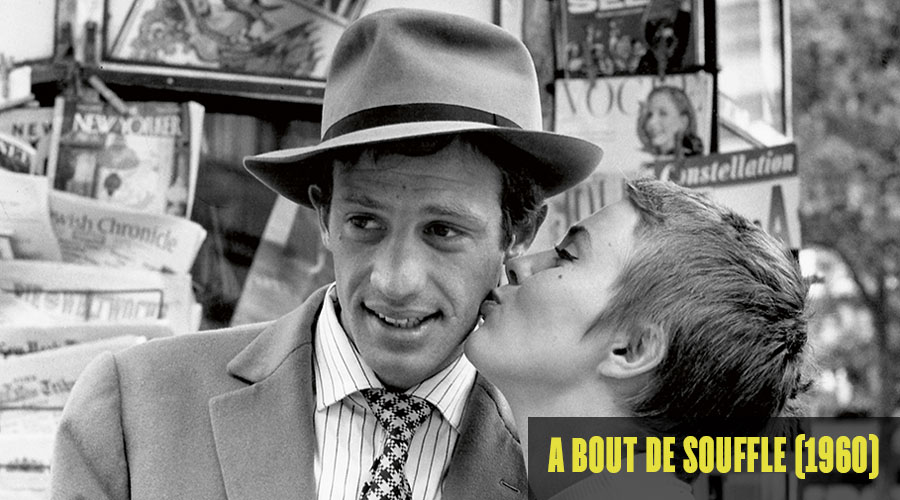

Despite its age, Tunes of Glory does not seem dated and its character-driven drama can still be understood today. However, it has disappeared somewhat from view: its traditional, almost theatrical approach to presenting the action made it seem old fashioned even on release compared to films of the French and British New Wave such as Jean-Luc Godard’s À bout de souffle or Karel Reisz’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, both released in the same year. Nonetheless, as Burgess says, the performances are ‘masterly’, and for fans of bagpipe music in particular there is much to enjoy.