Anthony Burgess in Chiswick

-

Andrew Biswell

- 29th March 2021

-

category

- Blog Posts

-

tagged as

- A Vision of Battlements

- Chiswick

- Deborah Rogers

- Enderby

- Enderby Outside

- Etchingham

- Glebe Street

- Guardian

- Here Comes Everybody

- James Joyce

- Journalism

- Liana Burgess

- Llewela Jones

- Llewela Wilson

- London

- Lynne Burgess

- Lynne Wilson

- Nothing Like The Sun

- Observer

- Paolo Andrea

- Penguin Books

- Shakespeare

- The Complete Enderby

- The Novel Now

- TLS

- Tremor of Intent

- Urgent Copy

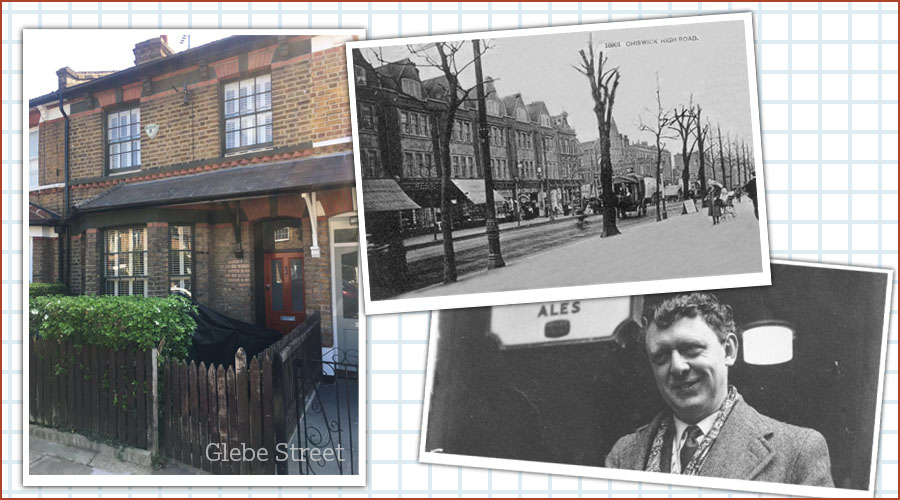

Anthony Burgess is well known as a writer from Manchester who lived in places such as Malaya and Monaco, but the period of his residence in London is less well documented. This article looks at the books and other writing projects he worked on during the five years he lived at 24 Glebe Street in Chiswick, West London.

In his autobiography, Burgess writes that he wanted to live in London because he was developing his broadcasting career. From 1960 onwards, he began to make regular appearances on BBC radio and television, but he found that the studios in West London were not easily accessible from his home in Etchingham, East Sussex.

He was also writing a regular column about television for the Listener, and the impending launch of BBC2 (the second BBC television channel) in April 1964 posed a problem: the new channel would only be broadcast in a limited number of regions, which did not include East Sussex. Burgess felt it was necessary, for professional reasons, to move to an area where BBC2 programmes could be watched and reviewed.

Burgess and his first wife Lynne bought their house on Glebe Street in 1963. The purchase of a 55-year lease was funded by an inheritance from Lynne’s father, who had died earlier that year. This house became their London base for the next five years, and it was here that Burgess wrote many of the best novels of his middle period, along with non-fiction books.

Burgess was much in demand as a journalist and cultural critic: in addition to writing regular book reviews for the Guardian, Observer and Times Literary Supplement, he worked as a theatre critic for the Spectator and as the opera critic of Queen magazine.

Deborah Rogers, who was Burgess’s literary agent in the late 1960s, was a regular visitor to the house on Glebe Street. She had strong memories of a white leather bar, which had been newly installed in the front room. By six o’clock each evening, she said, Lynne was often to be seen sliding off her bar-stool.

Interviewed in 1997, Rogers recalled the daily routine at the house in Chiswick:

[Burgess] would get up at seven in the morning and go down to this damp, lean-to kitchen. He’d let the dog out and the cat in. Then he’d get the ice out of the fridge and take it up to Lynne for her first gin of the day.

Surviving photographs suggest that Burgess did his writing on the dining table in the large open-plan living room on the ground floor.

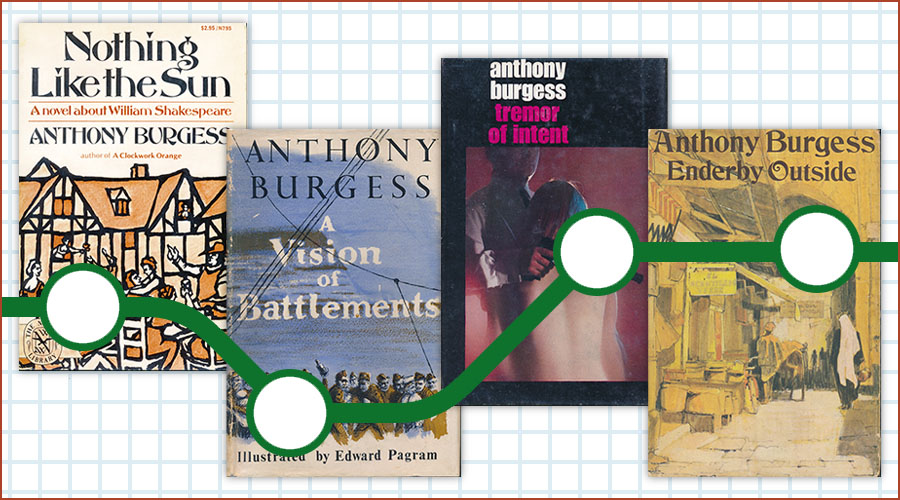

The first book he completed in Chiswick was Nothing Like the Sun, a bawdy novel about Shakespeare’s love-life, published on 23 April 1964 to approving reviews from the poet D.J. Enright and the lexicographer Eric Partridge. Written in a parody of Elizabethan English, this is one of Burgess’s most important and enduring works.

An option in the film rights was sold shortly after publication, and there was talk of adapting the novel for the stage. He was still living at Glebe Street when he was commissioned by Warner Brothers to write a musical film about Shakespeare in 1968. He wrote the script and the songs, but the film was abandoned when there was a change of management at the studio.

Nothing Like the Sun was followed by A Vision of Battlements, a modern reworking of Virgil’s Aeneid, set in Gibraltar during the Second World War. Burgess had written an unpublished first draft of this novel in 1952, and he revised it for publication in 1965, with illustrations by Edward Pagram. Burgess makes it clear in his introduction that the novel was intended as a homage to James Joyce, who had similarly updated the mythology of Homer’s Odyssey in his novel Ulysses.

His next novel was Tremor of Intent, an espionage thriller, intended as a comic critique of Ian Fleming and Leslie Charteris. The book describes the adventures of a British spy (a Lancashire Catholic, like Burgess himself) who travels to the Soviet Union to bring back an old school-friend who has defected to the USSR.

The form of the novel is another nod to Joyce’s Ulysses, as each chapter is written in a different narrative style. Burgess again makes use of his knowledge of Russian, which had previously been deployed in A Clockwork Orange and Honey for the Bears. The house on Glebe Street makes a fleeting appearance in Tremor of Intent, thinly disguised as ‘Globe Street’.

The last of his Chiswick novels is Enderby Outside, the second volume of the Enderby quartet, in which the bachelor poet goes on the run when he is wrongly accused of shooting a pop star. This book refers obliquely to Burgess’s friendship with Martin Bell, a frustrated poet who lived in Chiswick and wrote poems dedicated to Anthony and Lynne. Burgess composed the piano music which appears in Bell’s Collected Poems, and he reviewed the book warmly when it appeared in 1967.

Non-fiction publications from the Chiswick years included The Novel Today, a survey of contemporary fiction which drew on Burgess’s work as a book reviewer. Originally a 45-page pamphlet issued by the British Council and the National Book League, this work was later expanded to book length as The Novel Now, published by Faber in 1967.

Another book project for Faber was Here Comes Everybody, a detailed commentary on the complete novels and short stories of James Joyce. In his introduction, Burgess wrote:

I enfold here the wish that it will not be long before everybody comes to Joyce, seeing in him not tortuous puzzles, obscenity, and jesuitry gone mad, but one of the largest affirmations of man’s worth that this century has given us.

Reviewing Here Comes Everybody in the Observer, Philip Toynbee described it as ‘the best study of Joyce that I have ever read.’ Publication of the book in 1965 was accompanied by a BBC documentary about Joyce, presented by Burgess and titled Silence, Exile and Cunning. The following year he edited A Shorter Finnegans Wake, cutting down Joyce’s final masterpiece from 628 pages to just 278 pages.

The last of his Chiswick books was Urgent Copy, a collection of literary essays published by Jonathan Cape in 1968. One other unfinished project was a dictionary of slang, commissioned by James Cochrane at Penguin Books in 1967. Burgess worked on his dictionary for a few months, completing the letters A, B and Z, but he got no further with the task. The manuscript survives in the collection of the Burgess Foundation.

When Lynne collapsed with a hepatic portal haemorrhage in February 1968, she was admitted to Ealing Hospital, where she died on 20 March. A few weeks afterwards, Burgess resumed his friendship with Liana Macellari, an Italian translator who was living in Cambridge, and they were married in September of the same year. Liana moved into the house at Chiswick along with Paolo Andrea, her four-year-old son, who was later adopted by Burgess.

The following month, Burgess and Liana acquired a new house in Malta. They decided to leave Britain permanently, and they rented out the house on Glebe Street to a friend, a taxi driver called Terry Sutton, who agreed to pay four pounds a week in rent. This was an informal arrangement and there was never a written tenancy agreement, which caused trouble when disputes arose later on. Sutton had financial problems in the early 1970s, and he went on a rent strike when repairs to the windows were not carried out. The dispute was eventually resolved after Sutton made a complaint to the local council.

The property file at the Burgess Foundation indicates that Burgess sold the balance of the lease to Terry Sutton for £12,000 in 1982. After legal fees had been deducted, Burgess received about £11,000.

The five years that Burgess spent in Chiswick were among the most productive of his literary life. Although his fiction changed direction after he left England in 1968 and began a new European life in Malta and Rome, it is clear that his sojourn in West London produced many of the novels for which he is remembered.

In recent years there has been a proposal to install a blue plaque to commemorate Burgess’s period of residence in Chiswick. The list of major works he wrote there confirms it was a crucial time in his artistic life.