Anthony Burgess on The Wanting Seed

-

Anthony Burgess

- 21st August 2023

-

category

- Blog Posts

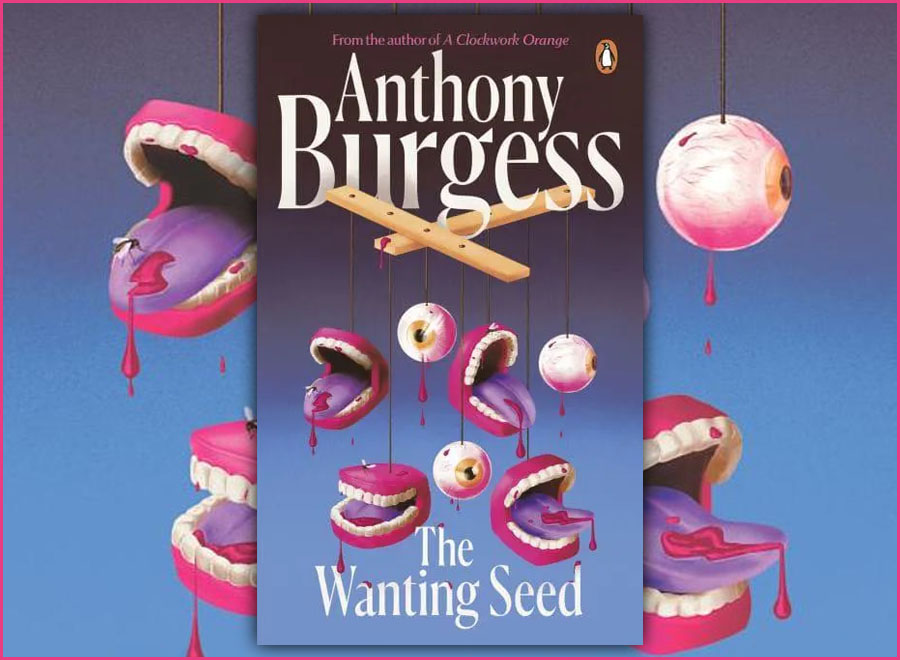

Burgess wrote this foreword to The Wanting Seed in 1982. The novel has recently appeared in Bulgarian and French. A new English edition has just been published in the Penguin Essentials collection.

The Wanting Seed appeared in the autumn of 1962, with A Clockwork Orange, my other piece of futfic or future-fiction, pairing it in the spring of that year. A Clockwork Orange was squeezed out of my appalled observation of youthful behaviour in an England which had become new and strange to me. In 1954 I had left a Britain suffering from shortages to live a hard-worked but moderately well-rewarded life in the Federation of Malaya. Returning to Britain in 1959, I felt very much a stranger in a land that now seemed affluent, telly-haunted, and burgeoning with a cult of youth. If the violence of the young, coupled with the reaffirmation of the necessity of evil in a world still animated by the right of moral choice, was the theme of A Clockwork Orange, its matching novel was concerned with a phenomenon I had been aware of while living in the East — the population explosion and the shrinking of the world’s food supply.

The Wanting Seed tries to show what England might be like if it suffered from the population of India. The response to the prospect of overcrowding and starvation might well be a culture which favoured sterility by promoting and rewarding self-castration. But, my instinct argued, nature might respond to human sterility with sterile patterns of its own, and the solution to the population problem could be more ruthless and more logical.

If the theological motto of A Clockwork Orange is ‘We must be free to make moral choices,’ that of The Wanting Seed is ‘Everyone has a right to be born.’ The history of a society is cyclical, as my hero Tristram Foxe teaches his overcrowded classes in a school of the future. Pessimistic conservatism, expecting the worst from man, does not always get the worst and hence is modified in the direction of optimistic socialism. But this latter creed, expecting the best from man, is usually disappointed, and disappointment is expressed in a greater governmental rigour, ending with downright tyranny (many tyrannical regimes have called themselves socialist). But tyranny ends in revolution and a restoration of the conservative philosophy: a perpetual waltz, the circle turning forever.

The book opens with the British government taking draconian steps to control births and ration food. But the people revolt and solve the great problem through cannibalism. When order is restored with the return of a conservative system, the cannibalistic innovation is rationalised into organised warfare, and the cadavers processed into canned protein in the supermarkets.

The book was regarded as a light, if dark, comedy, and nobody would take seriously that cannibalism might be the solution to the world’s crowding and hunger. I was told that all human flesh was toxic. Then came the Andes disaster and the survival of the fittest through the eating of their fellows. The survivors proved, on examination, to be well nourished but terribly constipated. I think it possible that one day we will find cans of meat in our markets called Mench or Munch, human flesh seasoned with sodium nitrate.

The book proclaims, in various of its lesser details, that it was written more than twenty years ago. Some of the African states I mention have changed their names, but there is no reason why they should not, in the distant future, change them back again. Anyway, this is not so much the future as a hypothetical projection, into an impossible time, of certain historical processes which I consider all too possible. The world of A Clockwork Orange was meant to be a real future (1972 or thereabouts) and it has already become the past. I cannot foresee the highly schematic world of The Wanting Seed as ever coming to birth, but I think some aspects of it are already with us.

The title comes from an old English folk song. This confuses ‘wanting’ and ‘wanton’. The ambiguity is appropriate to my book.