Anthony Burgess writes about VE Day: Everyone’s Free… Except Me

-

Burgess Foundation

- 8th May 2020

-

category

- Blog Posts

Anthony Burgess: Everyone’s Free … Except Me: One Man’s View from the Barrack Room

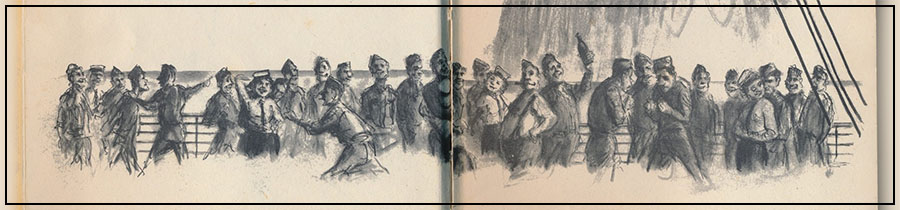

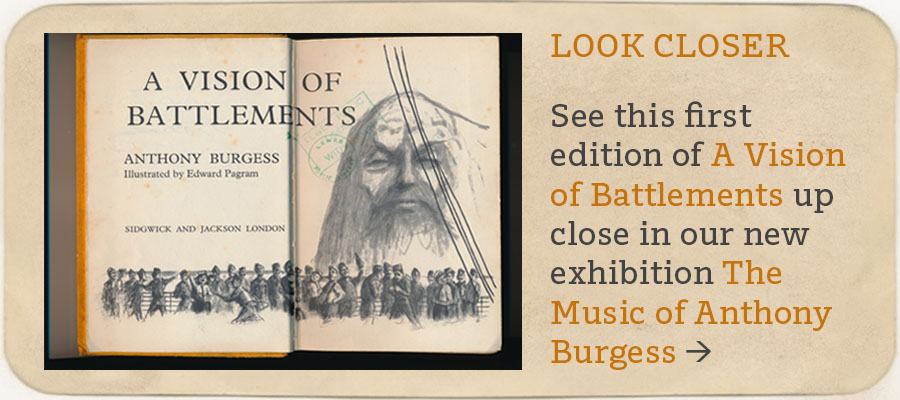

An edited version of this article was published in the Daily Mail on 8 May 1985 to commemorate the fortieth anniversary of VE Day. The complete text, reproduced here, appears in the Irwell Edition of A Vision of Battlements (Manchester University Press, 2017).

On 8 May 1660 the British monarchy was restored. On 8 May 1811 the Duke of Wellington trounced the French at Fuentes de Oñoro. On 8 May 1921 Sweden abolished the death penalty. 8 May in any year is the feast day of Wiro, Flechelm and Otger, whoever they were. That 8 May 1945 was VE Day sometimes eludes my memory.

I had got drunk the night before in anticipation of the rejoicing. When I woke very late and very ill, a Welshman named Ben Thomas was breathing smoke over me and saying: ‘The whole of fucking Europe is liberated except fucking you.’ He was a regimental sergeant-major and I was a warrant officer class two. We were in the barracks at Moorish Castle, Gibraltar and had been there for over two years, ready to stop the Germans marching in from Spain, with the kind permission of General Franco, and taking over the Rock. The Germans never did march in, and it was too late now. General Franco had played fair and neutral, ever the Christian gentleman. We had, in a sense, been wasting our time.

It was too late for the Germans, and it was too late for breakfast in the sergeants’ mess. Ben Thomas and I struck sparks with our boots all the way down the steep road from Moorish Castle to the Casemates and had a cup of chah and a wad in a café run by a moustached Spanish matron. The café was called the Trianon and was very dirty. Rough soldiers, already drunk, jeered at us because they no longer feared our rank. We promised them immediate transportation to the mysterious East, there to fight the Nips. The war, as Ben Thomas said, was not yet fucking over.

It was too late for the Germans, and it was too late for breakfast in the sergeants’ mess. Ben Thomas and I struck sparks with our boots all the way down the steep road from Moorish Castle to the Casemates and had a cup of chah and a wad in a café run by a moustached Spanish matron. The café was called the Trianon and was very dirty. Rough soldiers, already drunk, jeered at us because they no longer feared our rank. We promised them immediate transportation to the mysterious East, there to fight the Nips. The war, as Ben Thomas said, was not yet fucking over.

No, it was not. The rejoicing seemed premature to those of us who had a wider than European view of things. We did not know what horrors applied nuclear physics was preparing, and we assumed that the Japanese would fight to the last Kamikaze pilot. The war in Europe over, we were now made available for fighting in the jungle and expiring of beri-beri in Changi or somewhere. We feared the little yellow men; the Germans, though Nazis, were at least white. We left the Trianon and went to get drunk in the Garrison sergeants’ mess.

There some remarkable specialisations were represented, all already drunk — a master gunner, the drum major of the First Dorsets, a pioneer sergeant with a beard (the only rank in the army not required to shave), the glum comedian of the Garrison Concert Party, the editor of the Rock Magazine, an Irish engineer sergeant fighting leprechauns. They were all drenching palpable concern, especially the regulars: these had been jumped up in rank with the war; now, with peace, they would have to revert. Those of us who were not regulars had our own worries. There was a release scheme based on a coordination of age and date of joining up: troops would trickle back to civvy street so as not to swamp the labour market. I had worked out that I would join the trickle in May 1946 (this proved exact). Another year with only Japs to fight. Let’s have another drink.

I was 28. I had joined the army at 22. I would be 29 by the time I got out, perhaps older: was not Winston Churchill already warning of the need to maintain a large European army to face the Soviet menace? Winston Churchill was not popular with the conscripts; the regulars naturally liked the idea of a large army — who the enemy was was neither here nor there. What I tried to swill away now was the realisation that I’d missed nearly a whole decade of my life. I’d learned nothing except how to read company orders and do as little work as possible. What the hell was I to do in the real world where people worked for a living and even got sacked? Let’s have another drink.

There are times when you drink only to get more sober. This happened to Ben Thomas and me on VE Day in the Alameda Gardens, where beer tents had been set up and there were snarls because the barrels were beginning to run out. Then Ben Thomas began to have visions. He saw all the European dead marching to the tune of Cwm Rhondda towards a bonfire. The long repressed preacher in him started to come out and he assured the drinkers that hellfire awaited them: couldn’t they smell the stink of the everlasting conflagration that seethed under their bootsoles? I determined to get away from liberated Europe and visit fascist Spain.

I had fairly free access to Spain. One of my jobs had been to dress up as a civilian and spy on the transfer of British money to enemy agents. I dressed up as a civilian now but found I had no pesetas. There was a CQMS whom I particularly disliked. He, I knew, had in his quarters a large number of contraband wristwatches. I broke his table drawer open (splintery cheap wood anyway) and stole four. He had plenty more; he would not miss them. I exchanged these watches for a handful of pesetas with a barman on Main Street known as El Burro. Then I walked to the frontier, handed over the mandatory gift of two tins of issue Victory cigarettes to the unshaven Spanish guards (Orwell was to remember those cigarettes in Nineteen Eighty-Four) and then entered La Línea. There was no VE Day here.

I fought off the whores, mostly war widows or the wives of political detainees, and drank alone and sadly in bar after bar. Then I drank less sadly. I offered a drink to a member of the Guardia Civil. He refused. I took offence. I said, in impeccable Andalusian: ‘You spurn my hospitality because I belong to the forces that have, passively, alas, in my case, broken the forces of Italian and German fascism, leaving the stinking goat of a caudillo that you presumably idolise alone in Europe. His time is coming, mark my words.’ The policeman blew his whistle and two others appeared. I was taken to a Spanish lock-up. I remained there for three days.

Spanish lock-ups in those days were very filthy affairs, full of uncleaned vomit and stinking of Spanish urine, which is more aromatic than the British variety. There did not seem to be any catering facilities, but I shared a cell with a middle-aged Andalusian who, whatever his crime, was well-liked by the police, who permitted his little daughter to bring in garlic sausage, cheese, brick-hard bread, and vino tinto. These he shared with me and taught me flamenco songs like ‘My wife has run away. Long live gaiety’. After three days Ben Thomas managed to get to me. He pointed out the irony of my celebrating the death of fascism by being shoved into a fascist jail.

I got out on the plea of bad Spanish misunderstood by the Guardia Civil. I also said that I had been trying to get away from VE Day celebrations, which indiscreetly jeered at the downfall of a brother caudillo, and was drinking in Spain in memory of a great Anglo-Spanish victory over Napoleon’s peninsular army: 8 May 1811, at Fuentes d’Oñoro. When I got back to Gibraltar I faced big trouble — three days absence without leave on foreign territory. From this I learned that, despite VE Day, the war was not yet over. Or, put it another way, I was still in the army.