Anthony Burgess’s censorship scandal in Malta: a timeline

-

Andrew Biswell

- 10th June 2020

-

category

- Banned Books

10 June 2020 is the fiftieth anniversary of Burgess’s famous lecture, ‘Obscenity and the Arts’, which was delivered to a large audience at the University of Malta in Valletta.

In this blog, we look back on the story of Burgess’s lecture and the events which provoked it.

In November 1968, Burgess and his new wife Liana arrived in Malta with Paolo Andrea (aged four) to take possession of their new house at 168 Main Street in Lija. They had travelled by land and sea in a Bedford Dormobile (a motorised caravan).

As they drove south across Europe, taking a ferry from Italy to Malta, Burgess sat in the back with his typewriter. Burgess called this the ‘healthiest, most productive, most essentially human episode in my career.’

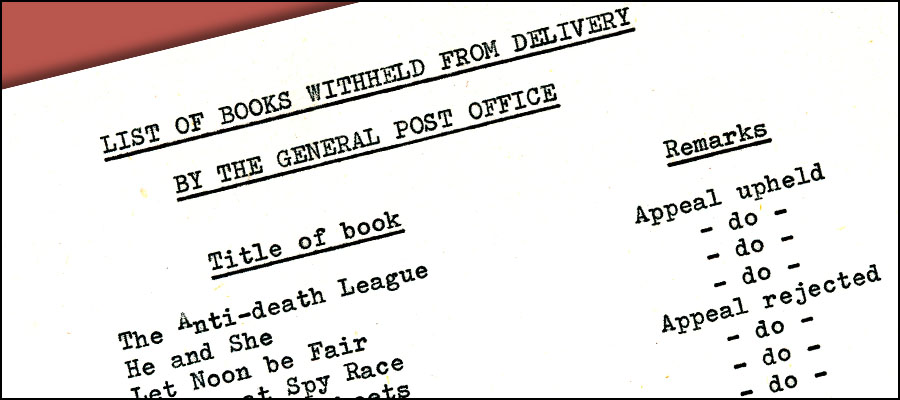

Early in 1969, Burgess’s books and other possessions arrived in Malta on a slow boat from England. On arrival, the books were inspected by Maltese customs officers, who were responsible for state censorship.

Forty-seven books were confiscated, of which 43 were destroyed by incineration. Burgess was given a list of the confiscated books, which survives in the archive in Manchester.

After lodging an appeal with the censorship panel, Burgess managed to retrieve his copies of four titles, including The Anti-Death League by Kingsley Amis — but books by Angela Carter, D.H. Lawrence and Dennis Wheatley were among those which were consumed by the flames.

In March 1970 Burgess and Liana visited New Zealand to take part in a literature festival.

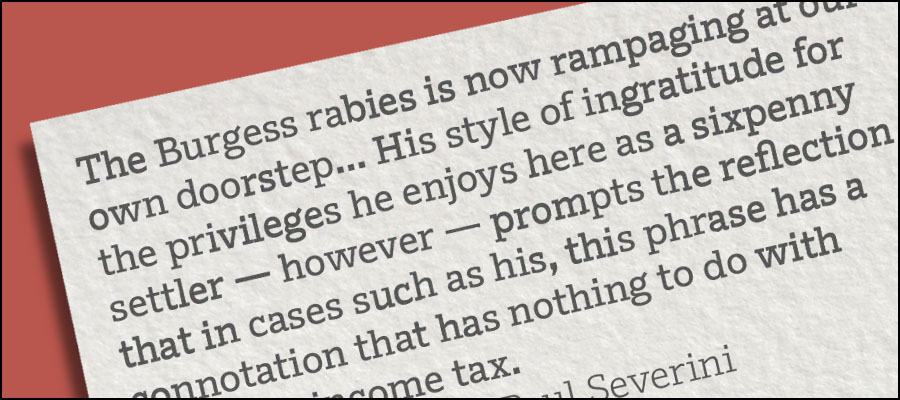

They gave an indiscreet interview to a newspaper there, in which they denounced the censorship regime in Malta. This interview was quoted at length in the Malta News. Burgess was attacked in editorials, and on the letters page by ‘Paul Severini’ (not his real name). He was accused of being a meddling foreigner and a ‘sixpenny settler’, a reference to the low rate of income tax in Malta, which was 6 pence in the pound.

Having returned to Malta to work on a new novel, and following further trouble with review books from the Sunday Times being confiscated, along with a French translation of his own novel, Tremor of Intent, Burgess accepted an invitation — from the Censorship Reform Group of the Malta Library Association — to give a public lecture at the university. His proposed titled was ‘Obscenity and the Arts’. This was one of the first occasions when pornography and obscenity had been openly discussed in Malta.

The weekend before the lecture was due to take place (on Sunday 7 June), Burgess was interviewed by Marie Said in the Sunday Times of Malta. He summarised his thoughts on obscenity. The publication of this interview gave his ideas a much wider circulation than the lecture alone would have done.

The lecture itself was delivered at the University of Malta on the evening of 10 June 1970. Burgess argued the case that literary merit should take precedence over any concerns for obscenity or pornography. He made reference to passages in the Bible, Virgil, Dante, Rabelais, and Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus. Listening intently among the 1,000-strong audience were priests and government officials.

Listen to an extract of the lecture in this animated video, produced especially for the lecture’s 50th anniversary.

Nobody could have predicted the level of scandal that followed. Immediately after the lecture, and over the next few months, the Sunday Times of Malta published a series of letters in which Burgess was attacked and defended by friends and enemies of literary censorship.

Some commentators regarded Burgess as a neo-colonialist who was trying to impose foreign values on a pious citizenry. To others, he was a champion of free speech who had found the courage to speak out against the excessive dominance of the Catholic Church over free expression in Malta.

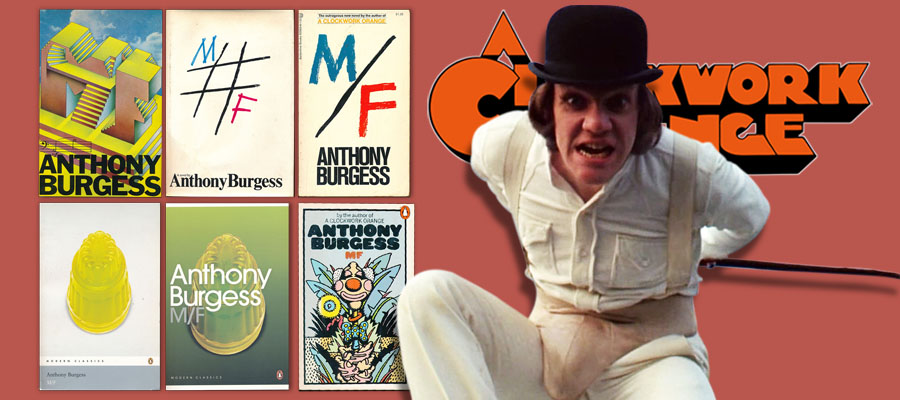

Undeterred by the controversy, Burgess published his novel MF in 1971. This spicy tale of incest and homosexuality is set on an island called Castita (meaning ‘Chastity’), which closely resembles Malta. It is likely that the novel was intended to cause offence to the Maltese pro-censorship lobby.

In January of 1972 Stanley Kubrick’s film version of A Clockwork Orange film was released worldwide. Burgess said of the controversy surrounding the film: ‘What hurts me, as also Kubrick, is the allegation made by some viewers and readers of A Clockwork Orange that there is a gratuitous indulgence in the violence which turns an intended homiletic work into a pornographic one.’

The film was banned in Malta until 2000.

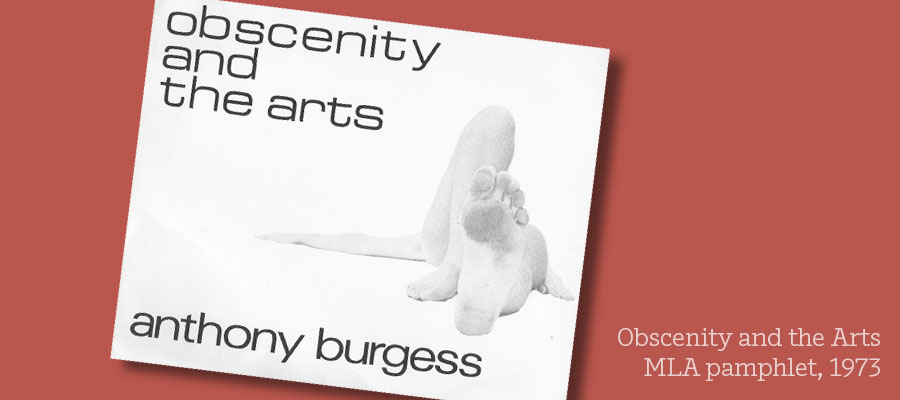

The lecture, Obscenity and the Arts, was published as a pamphlet by the Malta Library Association in 1973, transcribed from the original spools of magnetic tape. This gave another audience to Burgess’s criticisms of Maltese literary censorship, although few copies left Malta.

There were not many reviews of this limited first edition, but it received a thoughtful notice in Punch from John Sparrow, the Warden of All Souls College in Oxford.

The next episode was rather more dramatic. In the spring of 1974, Burgess returned from a visit to Italy to discover that his home had been confiscated by the Maltese government. He suspected foul play, and took the story to the Guardian, where it appeared as front-page news on 19 April 1974.

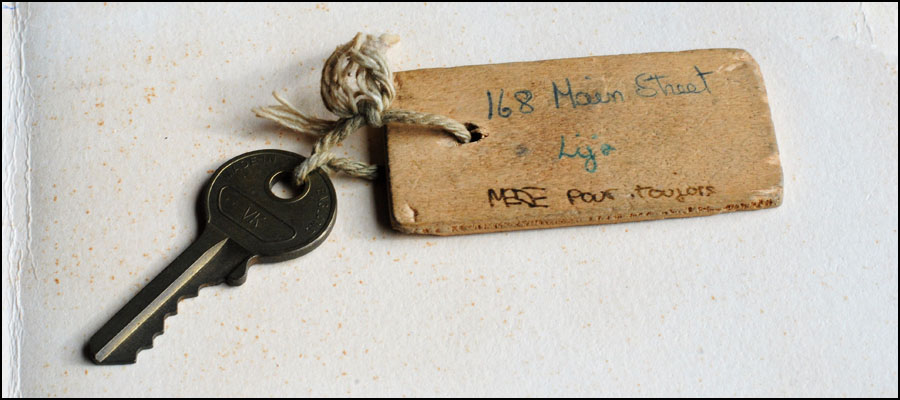

After further wrangling with the authorities, Burgess managed to get the house de-confiscated, but at this point Liana Burgess decided that she could no longer live under the government in Malta. The house at 168 Main Street in Lija (keys pictured) was rented out to the Australian ambassador, and the Burgess family moved out. They relocated to Rome, but their collection of books and furniture remained in Malta until the 1990s.

In 1980 Burgess published Earthly Powers, his longest and most ambitious novel, which contains an unflattering sketch of what Malta had been like in 1971. The hero of the novel, Kenneth Toomey, is forced to leave Malta when his house there is confiscated by the government, who disapprove of his homosexuality.

Burgess’s last word on Malta may be found in the second volume of his autobiography, You’ve Had Your Time, published in 1990, where he writes that he was very fond of his Maltese friends and neighbours, at the same time as disliking the political and religious systems which were dominant in the country when he was living there.

The final act in the saga came in 1998, when Liana Burgess decided to sell the house in Lija, and transferred the books to the newly-created Anthony Burgess Centre at the University of Angers in France.

Censorship in Malta was gradually relaxed over time, but it was still part of everyday life until 2016, when the law against staging ‘obscene’ and blasphemous plays was finally repealed. Burgess’s legacy as part of the cultural history of Malta was celebrated in a three-day festival in 2017, which included a symposium at the university and a world-premiere performance of the piano music he wrote there.

Burgess’s legendary lecture was published outside Malta for the first time in 2018, in an edition by Pariah Press, with a new biographical introduction, a selection of archive photographs taken by Anthony and Liana Burgess, an interview with Marie Said, and a polemical afterword from Germaine Greer.

After the unbanning of Kubrick’s film, the first translation of Burgess’s work came in 2019, when Teatru Malta presented a Maltese version of A Clockwork Orange to an audience of teenagers in Valletta.

Obscenity & the Arts is available at a special price of £7.99 (plus postage) if you order directly from Pariah Press.