Burgess and American Literature Part Three: Thomas Pynchon

-

Graham Foster

- 11th July 2013

-

category

- Blog Posts

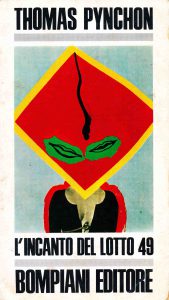

Anthony Burgess was extremely familiar with the work of Thomas Pynchon, and a quick search through the book collection at the International Anthony Burgess Foundation reveals a rare first edition of Gravity’s Rainbow (1973), and copies of Vineland (1990), V. (1961) and The Crying of Lot 49 (1966). In December 1963, Burgess met Liliana Macellari Johnson, who later became his second wife. Liliana (or Liana as she was usually called) was the Italian translator of both V. and The Crying of Lot 49 (L’incanto del Lotto 49). The Burgess Foundation archives contain Liana’s first edition copy of The Crying of Lot 49 with many translator’s annotations, and an inserted sheet where she has attempted translations of Pynchon’s verse sections of the novel.

Burgess himself included Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow as one of his Ninety-Nine Novels: The Best in English Since 1939, writing ‘this work, not yet as widely understood [as V. or The Crying of Lot 49], has a gravity more compelling than the rainbow technique (high colour, symbolism, prose tricks) would seem to imply’.

Telling the story of the Allied hunt for the ‘Schwarzgerät’, a Nazi rocket supposedly more deadly than the fearsome V2, Gravity’s Rainbow is a wild, exhausting and fragmented novel. At its heart is Tyrone Slothrop, an American Army Lieutenant who has undergone Pavlovian conditioning to make him sexually aroused in the presence of ‘Imipolex G’, the fictional plastic used in the manufacture of the rocket. Slothrop is sent to ‘The Zone’, a Wonderland version of Germany in the months following VE Day, to search for the rocket. Here, after meeting several strange characters and indulging in frequent coitus (quite possibly inspired by his Pavlovian condition), Slothrop gradually comes apart.

No summary can adequately address the complicated nature of Gravity’s Rainbow, and this is something that Burgess also struggles with. While he calls the novel ‘the war book to end them all’, he also largely ignores the complexity of both the plot and the novel’s structure. He also states that the subject of the novel is ‘clearly the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) of the Second World War’. Though, to an extent, much of the action of the first part of the novel is set in wartime London, it is a small part of a sprawling and often bewildering book that contains about 400 characters, from African-German Troops, to pornographic actresses, to witches and Russian spies. Burgess’s review focuses on a relatively minor character called Pudding, who appears in the first section, but vanishes for the majority of the novel, only to appear again, very briefly and in spectral form, in the final pages.

Even more curiously, the only copy of Gravity’s Rainbow in the collection at the Burgess Foundation is the American first edition (Viking Press). Toward the end of this edition, there is a printing error that replaces about 100 pages from the end of the novel, with 100 pages from the beginning of the novel. If Burgess did indeed only have this one copy of the book, then he did not have a complete version of the text, and the missing pages are vital to explaining both the novel’s cyclical structure and the plot (we find out the fate of Slothrop in these pages).

Nevertheless, Burgess did review Pynchon throughout his lifetime. A review of V. inspired a very brief piece of correspondence from Pynchon, after Burgess claimed that ‘Pynchon gives us Malta without having been there’. The secretive American wrote to Burgess demanding: ‘How do you know this?’ It is not known if Burgess replied to this missive.