Burgess and Hemingway

-

Andrew Biswell

- 7th July 2021

-

category

- Blog Posts

Ernest Hemingway died on 2 July 1961. Anthony Burgess was in Leningrad when he heard the news, gathering the material for Honey for the Bears and A Clockwork Orange. In a later review of A.E. Hotchner’s biography of Hemingway, reprinted in Urgent Copy (1968), Burgess recalled: ‘Many young Russians I drank with asked me, as if I had a chance of knowing better than they, whether it was murder or suicide: their Russian souls saw right through Mary Hemingway’s very sensible announcement that it was an accident, that he had merely been cleaning his guns.’

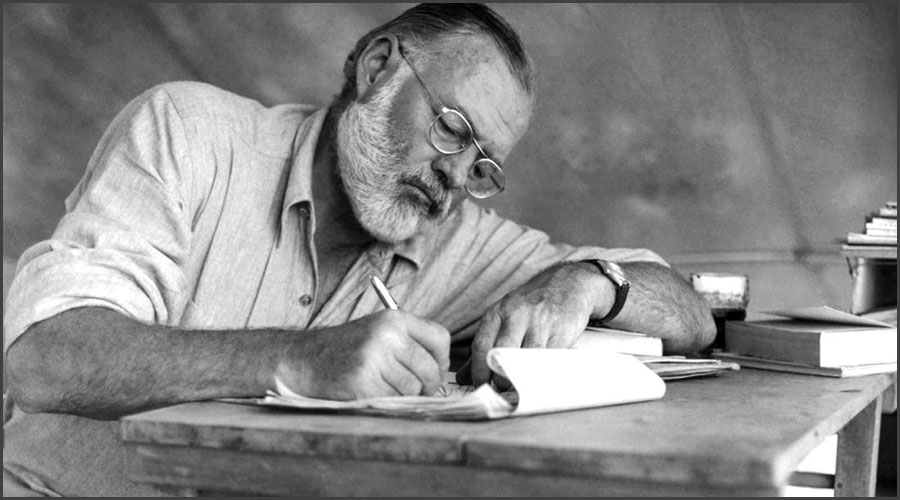

Hemingway ranks, along with D.H. Lawrence, very high in Burgess’s pantheon of twentieth-century literature. Although their lives and literature seem entirely different at first glance, Burgess wanted to probe the mysteries of these writers by devoting book-length studies to both of them. He began with a conviction that they were both reacting against modernity and the First World War: ‘D.H. Lawrence and Hemingway revolted against the higher centres; the subject-matter of both was instinctual, or natural, man.’ Whereas Lawrence came out of a non-conformist religious tradition of preaching and high rhetoric, Burgess argued that ‘Hemingway’s achievement was to create a style exactly fitted for the exclusion of the cerebral.’

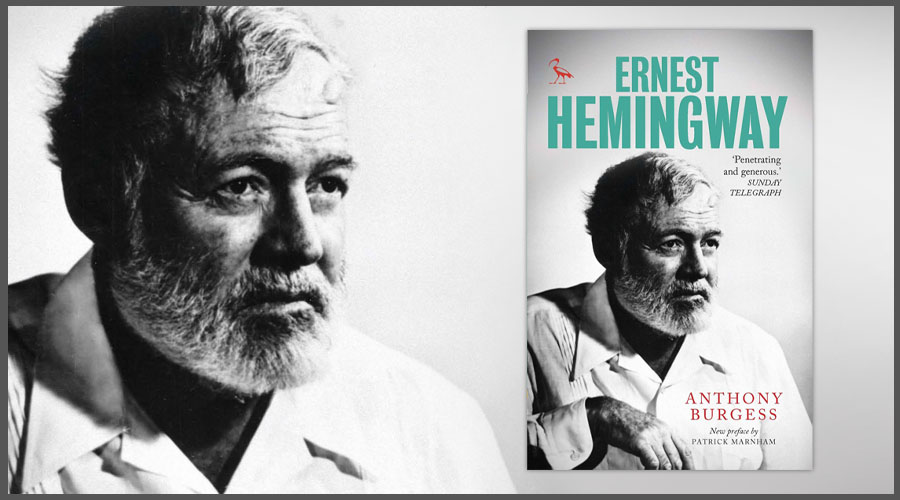

In 1978 Burgess published a full-scale biographical book, Ernest Hemingway and His World. In September of the same year, he travelled to Chicago, Idaho, Kansas and Key West to make a television film for The South Bank Show, produced for London Weekend Television by Melvyn Bragg and directed by Tony Cash.

Burgess says in the opening voice-over for his film, titled Grace Under Pressure: ‘The only thing I have in common with Ernest Hemingway is a vocation — the vocation of writer. For the rest, he was a big outdoor man, and I’m not. I don’t like guns, bulls, big fish, fighting. This means that I shouldn’t love Hemingway, but I do. He of all writers brought the novel out of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. Hemingway forged a new way of writing. This is why he’s important. Hemingway the human being? Well, that may be another matter.’

The film ends with scene filmed on a freezing morning in Ketchum, Idaho. Standing in hat and coat by the side of Hemingway’s grave, Burgess improvises a shivering monologue to camera about the last days of this great American writer:

‘What was the matter with Hemingway? Deterioration of the brain? Collapse of the body? That doesn’t explain anything. He wasn’t even old — only 61. He was disappointed, but who isn’t disappointed? He was a great creator of huge human characters, larger than life, and he assumed that the creator should at least be as big as his creations. He didn’t realise the abiding truth that the artist is always smaller than his art, and he tends to be smaller than ordinary people, if not physically then certainly morally.’

Yet Burgess’s final judgement on Hemingway is a positive one: ‘He wrote good and lived good, and both activities were the same. The pen handled with the accuracy of the rifle; sweat and dignity; bags of cojones.’

Ernest Hemingway is published in paperback by Tauris and available from Blackwell’s.