Burgess and the Atomic Age: The Monster We’ve Learned to Live With

-

Anthony Burgess

- 4th August 2020

-

category

- Blog Posts

Anthony Burgess published this essay to mark the fortieth anniversary of the destruction of Hiroshima in August 1985. It is reprinted here as part of our online series ‘Burgess and the Atomic Age’, which includes poetry, performance and new articles.

The Emperor Hirohito accepted the Allied terms on 14 August 1945, and Japan’s formal surrender was signed on 2 September. We forget these dates, but we don’t forget 6 August. Just forty years ago an atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, and the world has never been the same since.

Hiroshima is a port on the south coast of Honshu. Its population now is about 900,000. In 1945 it was 343,000, and the bomb claimed 136,989 of them. Those who merely died were the lucky ones.

The war up to 6 August 1945 had been a comparatively humane affair, the kind of mass slaughter that Napoleon would have understood. But now a new force – the release of the power of the sun from a microscopic particle – told us that apocalypse was on its way. Every day now we woke to the possibility that mankind will obliterate itself at the mere touch of a button. We did not feel like that before 6 August 1945.

The war up to 6 August 1945 had been a comparatively humane affair, the kind of mass slaughter that Napoleon would have understood. But now a new force – the release of the power of the sun from a microscopic particle – told us that apocalypse was on its way. Every day now we woke to the possibility that mankind will obliterate itself at the mere touch of a button. We did not feel like that before 6 August 1945.

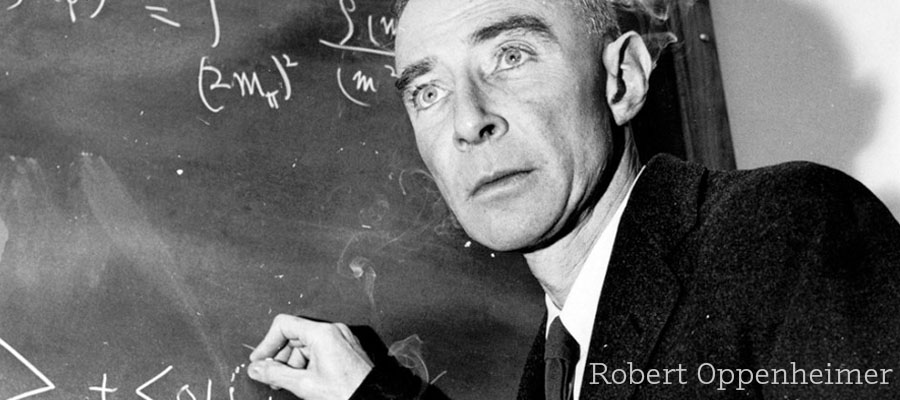

The bomb that fell on Hiroshima – and was duplicated a day or so later over Nagasaki – was an American invention, but it had its beginnings in England. Robert Oppenheimer, in charge of its development at Los Alamos, had worked with Sir Ernest Rutherford at Cambridge. To convert a blackboard dream into reality was a matter of drawing on the vast financial resources of the United States. Britain was out of it. The A-Bomb was a victory of money more than morality.

We know now, and we guessed then, that Japan was ready to surrender before 6 August 1945. The bomb was a mere lethal luxury. But such vast sums had been spent on it that it had to be used. Not to use it would have been like spending millions on an all-star Cinemascope production and then shoving the film in the trash can. So we all sat in the dark, munched our popcorn, and saw our show. It was brief but spectacular – a monstrous mushroom in the sky. It was worth the money. But we left the cinema feeling more depressed than elated.

Still, we thanked God that the great atomic secret was in the keeping of America, a land dedicated to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. We thanked God that Hitler had kindly kicked out Jewish scientific genius and wrecked his chance of having the bomb himself. We did not like the prospect of our great ally Uncle Joe Stalin getting hold of it. We comforted ourselves with thinking of the outrageous cost of the thing. It wasn’t an eighteen-shilling Sten gun or a twopenny Molotov cocktail. Nobody was going to be quick to let off another of those fireworks. Still, we weren’t happy. And, despite our telling ourselves that the Japs had bloody well asked for it, we couldn’t help feeling guilty.

I was an army instructor in those days, and the A-Bomb became one of the topics of platoon discussions. It was a topic almost stale from the start — like the Future of the British Commonwealth or the Glory of Parliamentary Democracy. I couldn’t fire interest in the sheer physical wonder of the thing — all that cosmic energy released from a substance smaller than a blackhead. I couldn’t fire interest in the historical future which contained bigger and better bombs. The only future that mattered to the yawning troops was the personal one – getting home, getting a job, get up them stairs.

As the forties moved on towards the fifties, the A-Bomb moved too. On 25 July 1946, a monster was loosed on Bikini Atoll in the Pacific, and the battleship Arkansas was sunk by the blast. Russia detonated a bomb in 1949 and Britain blasted the Monte Bello islands off Australia in 1952. But in that year the A-Bomb passed into ancient history. The Americans exploded the first hydrogen bomb at Eniwetok Atoll. We were into the H era. Oppenheimer objected to the new development in 1953 and was declared a security risk. He knew, if anyone did, what the pattern of the future was going to be like.

As the forties moved on towards the fifties, the A-Bomb moved too. On 25 July 1946, a monster was loosed on Bikini Atoll in the Pacific, and the battleship Arkansas was sunk by the blast. Russia detonated a bomb in 1949 and Britain blasted the Monte Bello islands off Australia in 1952. But in that year the A-Bomb passed into ancient history. The Americans exploded the first hydrogen bomb at Eniwetok Atoll. We were into the H era. Oppenheimer objected to the new development in 1953 and was declared a security risk. He knew, if anyone did, what the pattern of the future was going to be like.

Consider. The bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki had a destructive power equivalent to 20,000 tonnes of TNT. By the 1960s we had intercontinental nuclear warheads of a 100-megatonne capacity. I don’t know what we have in the 1980s. Like many people I have lost interest in the arithmetic of destruction. All you and I need to know is that the USA and the USSR between them have a nuclear stockpile big enough to destroy the planet. The mind boggles, thought stops. The end of mankind has become an itch in the middle of the back that goes on for ever and you can’t scratch. We live with the prospect, breathe it like the polluted air. It doesn’t really frighten us any more.

You can only gain some idea of the immense trauma caused by that old primitive A-Bomb when you read certain pieces of literature that are probably now out of print. Dame Edith Sitwell wrote a solemn poem called ‘Dirge for the New Sunrise’, precisely dated ‘Fifteen minutes past eight o’clock, on the morning of Monday, the 6th of August 1945,’ in which she saw herself hanging ‘between our Christ and the gap where the world was lost.’ A Caribbean calypso was rather more jaunty:

It was at the end of the Second World War

That the atom bomb fell on Hiroshima.

Though some folks called it an international crime,

Still it showed the progress of these modern times.

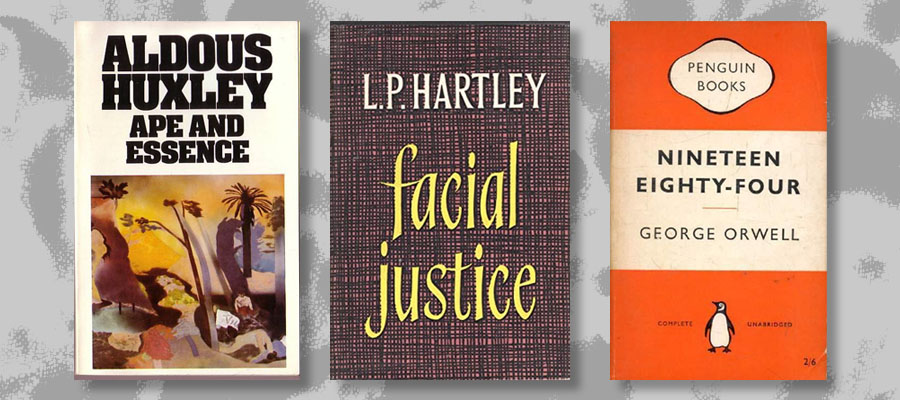

Aldous Huxley wrote Ape and Essence, a novel set in Southern California after the first and last atomic war which presented civilisation reverting to primitive devil worship – if you do homage to Satan perhaps he won’t send any more bombs. Sex is banned because it produces mutated monsters. The heroine of the book has four nipples, and she is comparatively normal.

L.P. Hartley produced Facial Justice, a story of the post-atomic future in which the world is full of guilt and everybody is named after a murderer. Such stories now seem naïve to us: their authors believed that there could be a future after a nuclear holocaust. After all, Hiroshima and Nagasaki were knocked to hell, but they survived. We don’t read many novels about survival now.

In his Nineteen Eighty-Four George Orwell saw that mankind’s survival depended on a gentleman’s agreement by the superpowers not to use the bomb. Warfare would not cease – indeed, it would go on all the time – but it would be conducted with conventional weapons. This seems to be our situation now. We have a damnably expensive equation in which one side cancels out the other. Neither the USA nor the USSR has the nuclear advantage. We can afford plenty of little wars, but nobody dare provoke the big final one. We don’t fear malevolence so much as we fear stupidity or an accident. We fear a left-handed man pressing a right-handed button.

At the beginning of the 1960s Stanley Kubrick produced his film Dr Strangelove, with its subtitle ‘How I stopped worrying and learned to love the Bomb.’ To be able to satirise the prospective world holocaust meant that we’d learned to put our fear in the wardrobe – a suit to be taken out occasionally but not to be worn all the time. Some day the sky may fall. Some day pigs may fly. We shrug and get on with the job. We don’t even worry about our grandchildren any more. Let them do their own worrying.

At the beginning of the 1960s Stanley Kubrick produced his film Dr Strangelove, with its subtitle ‘How I stopped worrying and learned to love the Bomb.’ To be able to satirise the prospective world holocaust meant that we’d learned to put our fear in the wardrobe – a suit to be taken out occasionally but not to be worn all the time. Some day the sky may fall. Some day pigs may fly. We shrug and get on with the job. We don’t even worry about our grandchildren any more. Let them do their own worrying.

1985 is the occasion for a fortieth-anniversary look back at a time which now seems very remote. 1945 was Year One of the Nuclear Age we’re living in, but we’re also living in the Alphabetic Age, and that started about 3000 BC. That old bomb which devastated Hiroshima doesn’t look – to today’s kids who see it on documentaries – like a portent of a terrible future. It’s big but cosy – like the Nazis and Glenn Miller. We’ve done better than that since then.

The trouble is not how we wage war but war itself. Granted the bow and arrow and the Lee Enfield, you’re bound to end up with the H-Bomb. The only new thing that began in 1945 was the idea that you could have a weapon you were too scared to use. I suppose that can be called a kind of progress.

Text copyright © International Anthony Burgess Foundation. Not to be reproduced without permission.