Burgess on Joyce: Here Comes Everybody

-

Burgess Foundation

- 3rd July 2019

-

category

- Blog Posts

Here Comes Everybody, subtitled ‘An Introduction to James Joyce for the Ordinary Reader’, was commissioned by Joyce’s own publishers, Faber and Faber, in 1963. Burgess’s original title was ‘James Joyce and the Common Man’, and he introduces the book with a provocative statement: ‘If ever there was a writer for the people, Joyce was that writer.’

Here Comes Everybody was Burgess’s third non-fiction book, following in the wake of English Literature: A Survey for Students (1958) and Language Made Plain (1964). Written between January and August 1964, Here Comes Everybody was published in 1965. The American edition, published by Norton in the same year, was retitled Re Joyce. The book was widely reviewed on publication, and it quickly established itself as a useful guide to Joyce’s work.

Burgess divides Here Comes Everybody into three sections. The discussion proceeds chronologically, taking in each of Joyce’s early published works (there are chapters on Chamber Music, Dubliners, Exiles, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Stephen Hero) before devoting longer sections to each of Joyce’s more substantial books: Ulysses and Finnegans Wake. Each chapter offers guidance for deciphering Joyce’s mythological allusions, images and omnilingual experimental writing. Some of this material is drawn from commentators such as Stuart Gilbert and Frank Budgen, although Burgess does not take much trouble to acknowledge his sources.

The book was very positively received, and critics praised Burgess for providing a starting point for anyone who wanted to understand Joyce’s work. Denis Donoghue wrote in the New Statesman that Burgess wanted ‘to rescue Joyce from Professor X and give the whole oeuvre to you, mate.’ Writing in the Listener, W.R. Rodgers described Burgess’s book as a ‘pilot-commentary’ which was ‘both useful and enthusiastic.’ The Economist’s book critic wrote that Here Comes Everybody was ‘honestly and agreeably written.’ An anonymous reviewer in the Times Literary Supplement said, not unkindly, that the detailed commentary on Finnegans Wake was ‘long but never tedious.’

The most effusive praise came from Philip Toynbee, chief book critic of the Observer, who said that Burgess had written ‘the best study of Joyce that I have ever read — good humoured and modest, learned but full of a considered enthusiasm which will make many of us turn back to Ulysses and some of us, perhaps, try again to penetrate the tough nutshell of Finnegans Wake.’

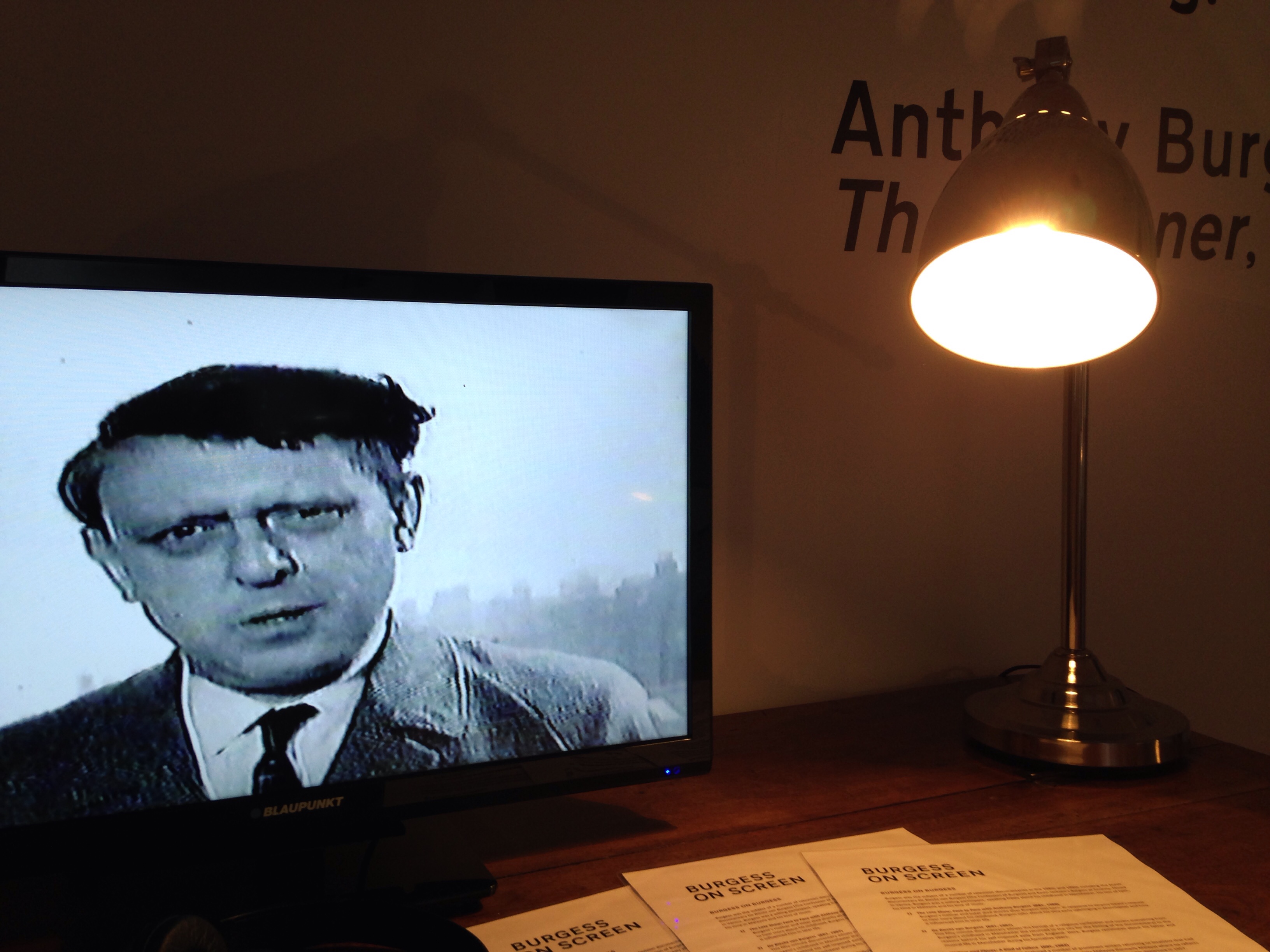

While Burgess was writing Here Comes Everybody, he also worked on a television film about Joyce for the BBC’s Monitor series (edited by Huw Wheldon and Jonathan Miller), broadcast on 20 April 1965 under the title Silence, Exile and Cunning. This film was directed by Christopher Burstall, to whom Burgess dedicated Here Comes Everybody. An extract from his script was published in the Listener on 22 April 1965. In this article Burgess claimed that his commentary had not been ‘coldly composed, like literature, but shiveringly improvised on camera.’ The documentary, filmed on location in Dublin, is a visual companion piece to Here Comes Everybody, and it covers much of the same ground. However, the documentary includes some autobiographical reflections which are absent from the book, as Burgess describes his own discovery of Joyce, and speaks about the importance of Joyce’s writing in his own creative life.

Shortly after Here Comes Everybody had appeared, Burgess was invited by Faber to edit A Shorter Finnegans Wake. This was an attempt, through a combination of summary and Joyce’s own writing, to make Finnegans Wake more digestible for the ordinary reader. In his long introduction, Burgess is keen to emphasise the pleasure of reading Joyce’s novel: ‘We ought to put off the mask of solemnity and prepare to be entertained. This is one of the most entertaining books ever written.’

Burgess returned to Joyce on various other occasions throughout his career. In 1973, shortly after he had taught a course on Ulysses at City College in New York, he was commissioned by the editors at André Deutsch to write Joysprick, a full-length book about the language of James Joyce, published in their ‘Language Library’ series. The tone of this work is more relaxed and writerly than Here Comes Everybody, and it includes parodies and rewrites of Joyce’s work. Borrowing a distinction from the book, the critic Richard Luckett wrote in the Spectator that Burgess had produced ‘a splendid rewrite of the opening of Ulysses in language appropriate to an American Class 1 novelist.’ The Times Literary Supplement welcomed Burgess’s second Joyce book as a work whose value lay in suggesting a new critical approach to the Joyce canon, based on linguistic analysis.

Burgess’s next major reckoning with Joyce came in 1982, when BBC Radio 3 and Raidió Teilifís Éireann (RTE) jointly broadcast a radio production of Blooms of Dublin, a musical play based on Ulysses. This adaptation captures the bawdy and comedic elements of Joyce’s novel in songs such as ‘Copulation without Population’ and ‘Warm Full-Blooded Life’. Burgess had been working on the musical since 1965, and he continued to revise it after Hutchinson published the text in 1986. Working with his wife Liana, he made an Italian translation of Blooms of Dublin towards the end of his life in 1993, but this play with music has never been presented on the stage, as he intended.

One other discovery has recently come to light: an American television programme from 1973 called Lots of Fun at Finnegans Wake, in which Burgess presents a lecture on Joyce in a mocked-up Irish pub, with a pint of Guinness in his hand. A copy of this broadcast has been added to the Burgess Foundation’s audio-visual archive and is available for researchers to consult in the reading room.

It is clear from these examples that Joyce was a major influence on Burgess’s writing, and on his wider practice of literature, language and music. The abundance of this published work demonstrates that Joyce was rarely out of his thoughts. Now that Here Comes Everybody is back in print, it is possible for a new generation of readers to discover Burgess’s enormous enthusiasm for Joyce and his copious canon of literary work.