Burgess versus Mary Whitehouse

-

Andrew Biswell

- 21st April 2021

-

category

- Banned Books

One of the key episodes in Earthly Powers is the trial scene in chapter 64, where Kenneth Toomey stands up in a London magistrate’s court to defend a fellow writer who has been accused of publishing a blasphemous poem. In the course of giving evidence, Toomey makes a public declaration of his homosexuality, which he has concealed from everyone except his closest friends until this point. Because his sexuality was regarded as a crime under English law until 1967, Toomey is forced to leave England and to live in exile abroad, as many real-life writers of his generation had done.

The fictional trial has its origins in two legal cases. The first of these was an obscenity case arising from the novel Last Exit to Brooklyn by Hubert Selby. When the British edition of the novel appeared in 1966, questions were asked in the House of Commons, and a private prosecution under the 1959 Obscene Publications Act was brought by Sir Cyril Black, the Conservative MP for Wimbledon.

The fictional trial has its origins in two legal cases. The first of these was an obscenity case arising from the novel Last Exit to Brooklyn by Hubert Selby. When the British edition of the novel appeared in 1966, questions were asked in the House of Commons, and a private prosecution under the 1959 Obscene Publications Act was brought by Sir Cyril Black, the Conservative MP for Wimbledon.

At the trial, Burgess gave expert evidence for the defence about the literary merit of Selby’s book, arguing that it was a work of art, not intended to be pornographic. The publishers of the novel, John Calder and Marion Boyars, lost the case, but this judgement was overturned in the Court of Appeal in 1968. Burgess was asked to write an introduction to the post-trial edition, published in the same year.

The second case is more immediately relevant to Earthly Powers. In 1976, the anti-pornography campaigner Mary Whitehouse brought a private prosecution for blasphemy against the magazine Gay News, which had published, on 3 June 1976, a poem by James Kirkup titled ‘The Love That Dares to Speak Its Name’.

Kirkup’s poem is an erotic fantasy about the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. The speaker, who claims to have been present at this event, speculates about possible relationships between Jesus and various other characters who appear in the Gospels:

I knew he’d had it off with other men — / with Herod’s guards, with Pontius Pilate, / with John the Baptist, with Paul of Tarsus, / with foxy Judas, a great kisser, with / the rest of all the twelve, together and apart.

The poem appeared with an illustration depicting Christ on the cross with (as Alan Travis tell us in his book, Bound and Gagged), ‘a large penis.’

Whitehouse complained about the poem itself and the illustration, which she also regarded as blasphemous. She was the self-appointed leader of an organisation called The National Viewers’ and Listeners’ Association, which set out to purify British culture and restore it to a state of decency, informed by the values of conservative Christianity.

After numerous skirmishes with radio and television producers, Whitehouse turned her attention to Gay News. Some commentators wondered why she had been reading this magazine with such close attention, but Whitehouse claimed that a copy of the poem had been posted to her by a friend.

Mary Whitehouse’s lawyers advised against taking action against Kirkup, who was a distinguished poet and a professor of English. Instead, they concentrated their fire on Denis Lemon, the editor of Gay News, who was notorious for his anti-religious views and was therefore thought to be a softer target.

Mary Whitehouse’s lawyers advised against taking action against Kirkup, who was a distinguished poet and a professor of English. Instead, they concentrated their fire on Denis Lemon, the editor of Gay News, who was notorious for his anti-religious views and was therefore thought to be a softer target.

Citing the little-known Blasphemy Act of 1697, the lawyers acting for Whitehouse filed a writ for ‘blasphemous libel’ against the magazine and its editor. As the Blasphemy Act had not been used in the English courts since 1921, there was considerable media interest in the Whitehouse v. Lemon case.

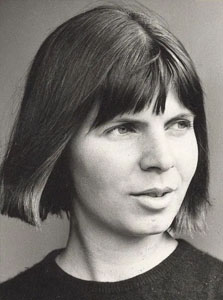

The trial took place at the Central Criminal Court in London in 1977. The writers Margaret Drabble (pictured) and Bernard Levin gave evidence in support of Kirkup’s poem and Gay News, while the novelist and barrister John Mortimer joined forces with the human rights lawyer Geoffrey Robertson on the legal team for the defence.

The verdict went against Gay News, and the judge told Denis Lemon that he had only narrowly avoided being sent to prison. Lemon received a fine of £500 and a suspended prison sentence of nine months, which was later quashed in the Court of Appeal. Gay News was fined £1000 and forced to pay Mrs Whitehouse’s legal costs. The magazine recovered from this setback with the support of public donations, and it continued to publish until 1983.

Burgess sticks fairly close to the facts of this case in his fictional reworking of the Gay News trial. The collection of poems which is put on trial in Earthly Powers is called The Love Songs of J. Christ — an obvious echo of ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’ by T.S. Eliot. The fictional author, Valentine Wrigley, is one of Kenneth Toomey’s former lovers and a well-known poet. When his erotic poems about Jesus are put on trial, Toomey agrees to give evidence for the defence, and outs himself as gay while doing so.

Although the texts of Wrigley’s poems are not quoted in the novel, Toomey says that they resemble a short story called ‘The Man Who Died’ by D.H. Lawrence. Questioned about the style of the poetry, Toomey compares it to the works of Henry Miller and James Joyce. The barrister for the prosecution, George Pyle, summarises it thus: ‘The sound of Judas’s ah ecstasy is likened to the tinkle of thirty pieces of silver. St Peter is complimented on his lusty fisherman’s rod.’ Such writing is said by Toomey to be in a ‘long and distinguished artistic tradition’ which began with the Song of Solomon in the Bible.

It is clear that Burgess took the opportunity, in Earthly Powers, to respond in a direct way to the recent history of the James Kirkup trial, which would have been familiar to many readers when the novel was published in 1980.

There is another little-known connection between Burgess and Mary Whitehouse. When Burgess translated Belli’s religious sonnets in ABBA ABBA, he did so in the knowledge that the original poems had been considered unpublishable in Belli’s lifetime and for many years after his death. Belli took stories from the Bible and rewrote them in the language of the streets. Burgess’s translations into Lancashire dialect echo the obscenities which were present in the original sonnets.

In his introduction to the Irwell Edition of ABBA ABBA, Paul Howard quotes Burgess as saying that Mary Whitehouse wanted to ban his novel. This was not quite true, but his publishers at Faber and Faber were certainly worried about the risk of another prosecution for blasphemy.

In his introduction to the Irwell Edition of ABBA ABBA, Paul Howard quotes Burgess as saying that Mary Whitehouse wanted to ban his novel. This was not quite true, but his publishers at Faber and Faber were certainly worried about the risk of another prosecution for blasphemy.

When the first edition was published in 1977, a few weeks after the Kirkup trial, Faber persuaded Burgess to drop his intended title, which was ‘Belli’s Blasphemous Bible’ or ‘A Bible for Blasphemers’. They feared that any talk of blasphemy would be a red rag to Mary Whitehouse, whose puritanical zeal had been boosted by her triumph over Gay News. No doubt there were sighs of relief at Faber when the publication of ABBA ABBA was not followed by any threats of legal action.

In the end, there was some disappointment on Burgess’s part that nobody wanted to bring a blasphemy case against ABBA ABBA. No doubt he would have enjoyed having his day in court, as Toomey does in Earthly Powers. Nevertheless, blasphemy remained a preoccupation in his writing. When the Ayatollah Khomeini proclaimed a death sentence against Salman Rushdie in February 1989, Burgess was quick to defend Rushdie’s novel The Satanic Verses on the radio and in the pages of the Irish Times and the Independent. In April 1989 Burgess wrote a long poem, ‘An Essay on Censorship’, which responds to the Rushdie affair and the religious controversies which surrounded it. This poem is included in the volume of Burgess’s Collected Poems, published by Carcanet in 2020.

James Kirkup died in 2009 at the age of 91. When his poem was read aloud to an audience in Trafalgar Square in 2002, no action was taken by the police. The offence of blasphemous libel was finally abolished in England and Wales in 2008.

After the 1977 trial, Denis Lemon sold Gay News, left journalism, and went into the restaurant business. He died in 1994. In his obituary, he was quoted as saying that Kirkup’s poem was ‘probably not a great work of literature.’

Further reading:

Dominic Sandbrook, Seasons in the Sun: The Battle for Britain, 1974-1979 (Penguin, 2012)

Alan Travis, Bound and Gagged: A Secret History of Obscenity in Britain (Fourth Estate, 2000)