Burgess’s fictional afterlives – part three, Burgess and Erica Jong

-

Burgess Foundation

- 28th October 2011

-

category

- Blog Posts

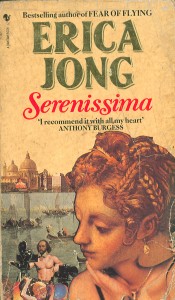

Burgess began to appear as a fictional character in Anglophone literature in the 1980s. His earliest manifestation in an English language novel (other than his own) was an off-stage cameo in Erica Jong’s novel of Venice, Serenissima, in 1987.

Burgess and Jong were friends, as he reports in his autobiography You’ve Had Your Time. He was a generous critic of Jong’s, having included her second novel How to Save Your Own Life in his list of 99 great post-war novels. He also praised her picaresque novel Fanny highly for the Saturday Review, even claiming she had ‘gone further than Joyce’ linguistically with her pastiche of eighteenth-century novels and their language. Other critics have not rated either book quite so highly.

Burgess and Jong were friends, as he reports in his autobiography You’ve Had Your Time. He was a generous critic of Jong’s, having included her second novel How to Save Your Own Life in his list of 99 great post-war novels. He also praised her picaresque novel Fanny highly for the Saturday Review, even claiming she had ‘gone further than Joyce’ linguistically with her pastiche of eighteenth-century novels and their language. Other critics have not rated either book quite so highly.

In return, Jong’s tribute to Burgess seems somewhat measly. Serenissima, which was later renamed as Shylock’s Daughter, tells the story of an ageing Hollywood actress, Jessica Pruitt, who is separated from her only child and seeks solace by taking up a role as judge at the Venice Film Festival, after which she hopes to star in a movie based on The Merchant of Venice to be filmed by a sensitive Swedish auteur, one of her many former lovers.

story of an ageing Hollywood actress, Jessica Pruitt, who is separated from her only child and seeks solace by taking up a role as judge at the Venice Film Festival, after which she hopes to star in a movie based on The Merchant of Venice to be filmed by a sensitive Swedish auteur, one of her many former lovers.

Following a debacle at the screening of his last movie, the director Björn Persson (a thinly veiled Ingmar Bergmann) abandons Venice abruptly, leaving Jessica waiting feverishly in Venice for the shoot to begin. Then she hears from her co-star that Persson has gone to visit Anthony Burgess:

‘Per shrugs, then changes the subject. He is a political animal, not a poetic one. ‘Listen, Yessica, I have not heard from Björn directly, but Lilli has communicated with me. She and Björn are in Lugano, staying with Anthony and Liana Burgess. They are in hiding, so to say. Björn is trying to get the financing for Serenissima back on track…”

Serenissima morphs into a time-travelling fantasia where Jessica encounters Shakespeare and the Earl of Southampton on holiday in 16th century Venice. The novel seems to borrow extensively from Burgess’s own Shakespeare work in a number of instances. Serenissima, like Nothing Like The Sun, features an art-inspiring Muse (Jessica’s is Robert Graves’s White Goddess), and accepts the idea that Shakespeare contracted syphilis. The idea of a time traveller encountering Shakespeare and feeding him his own lines, as Jessica does, is the subject of a sci-fi short story that Burgess wrote for Enderby in Enderby’s Dark Lady.

Anthony Burgess never appears in Serenissima, but his influence is so significant upon it that perhaps Erica Jong felt it would be a fitting tribute to mention him within the text. However, Burgess himself later protested that this cameo was inaccurate, for the simple reason that he and Liana never had any guests. Erica Jong ‘probably has a vision of something like Baron Thyssen’s Villa Favorita or the Milanese mansion that glowers on the hill above us,’ he wrote. ‘We rest in the comparative humility proper to a writer and his wife, and nobody comes to stay with us. Perhaps astonishingly, we find that we have no friends. We do not, of course, need them.’