Chest of curiosities: exploring Anthony Burgess archive recordings

The Foundation supports academic study into Anthony Burgess. In this third guest blog post (read the first one here and the second one here), PhD researcher Milena Schwab-Graham writes about her work on the extensive Anthony Burgess cassette tape collection.

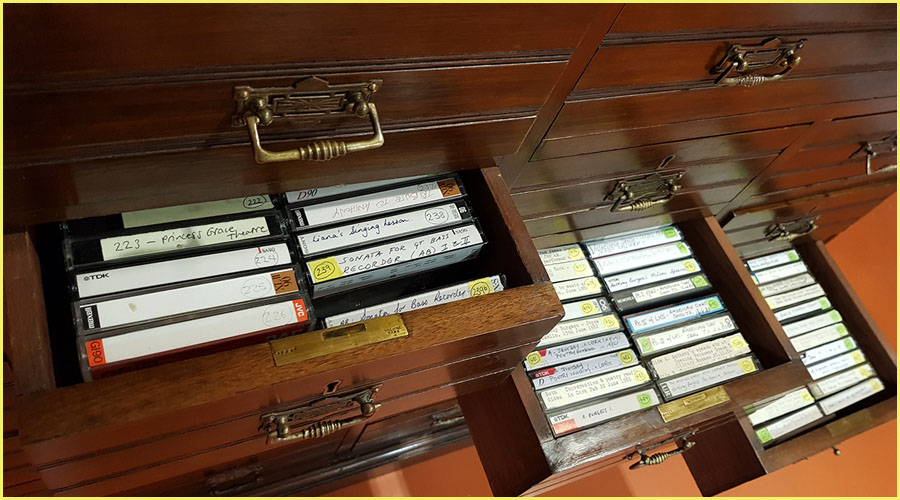

In the midst of the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, the chance to travel to the International Anthony Burgess Foundation in Manchester was a rare and very welcome opportunity. Having spent the past few months conducting remote archival work as a researcher for the ‘Anthony Burgess on Tape’ project, cataloguing a selection of lecture and interview recordings, it was exciting to experience the materiality of Burgess’s recordings up close. These can be found in the reading room of the Burgess Foundation, whose cool air and shelves lined with volumes from Burgess’s library provided a welcome respite from the heat outside. Adjoining storerooms house a plethora of Burgess ephemera, including furniture, manuscripts, and ornaments. The instruments of Burgess’s craft – his typewriters, and his grand and upright pianos – are also on display. Having become used to hearing Burgess’ disembodied voice via digitised recordings, it was a thrill to see the wooden chest in which the archived recordings are stored, its drawers filled with dozens of cassette tapes with handwritten sleeve notes.

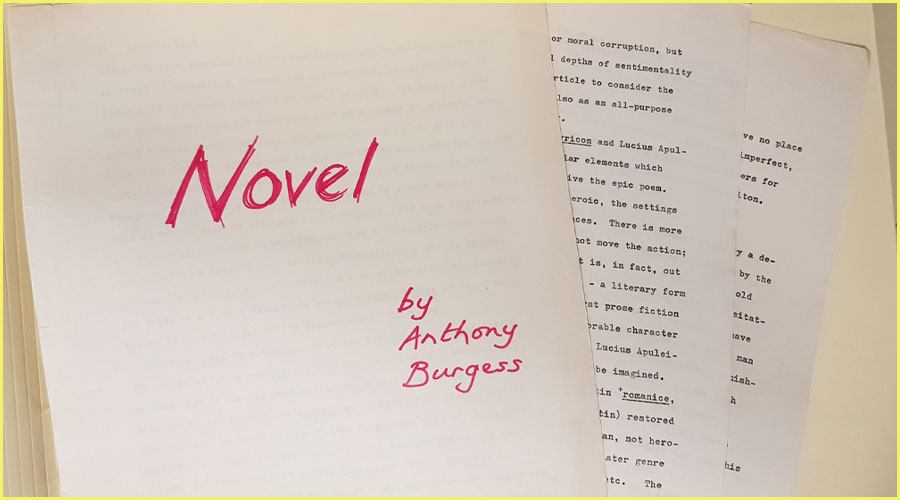

Throughout the course of the project, my interest, as a doctoral researcher in English Literature, has been piqued by the ways in which Burgess describes his relationship to his creative processes, and his approach to novel writing in particular. This has, in turn, lead to a curiosity regarding his extensive works of literary criticism, among them Urgent Copy (1968), They Wrote in English (1979) and Ninety-Nine Novels: the best in English since 1939 (1984), which I was able to explore in greater depth in the Burgess Foundation reading room. With the support of the Archivist, Anna, it was also possible to gain access to a number of typescripts held in the archives, some of which are yet to be published. These included the typescript titled ‘Novel’, which was first written in 1975. It lay undiscovered in Burgess’s and his second wife Liana’s Bracciano residence in Italy, until it became one of the items which formed the incipient collection of the Burgess Foundation in 2005.

In 2019 it was published for the first time as On the Novel. In this work, Burgess continues his project of defining the modus operandi of the novel form which he had begun in the 1960s. His caustic humour is in full effect when, in Urgent Copy (1968), he warns of writing, and indeed literary reviewing, as hazardous activities:

Book-writing is hard on the brain and excruciating on the body: it engenders tobacco-addiction, an over-reliance on caffeine and dexedrine, piles, dyspepsia, chronic anxiety, sexual impotence. Behind the new bad book one is asked to review lie untold misery and very little hope. One’s heart, stomach and anal tract go out to the doomed aspirant.

In ‘Novel’/On the Novel (1975/2019), Burgess continues to explore the symbiotic relationship between novel writing and literary criticism, citing how ‘Great literature and great criticism possess in common a sort of penumbra of wide but unsystematic learning, a devotion to civilised values, an awareness of tradition, and a willingness to rely occasionally on the irrational and intuitive.’

Burgess returns to the ‘irrational and intuitive’ process of writing in his radio interview with Larry King for the Larry King Show on 12 August 1980, during a segment on the conception of his novel Earthly Powers (1980). Here, Burgess reiterates the unknowability and arbitrariness inherent to the writing process: ‘If you know where you’re going, you’d better not write the novel, because it will cease to be an adventure’. In Burgess’s view, characters are beyond the writer’s control. He cites his experiences of teaching creative writing at US colleges, revealing the difficulty inherent to equipping others with creative writing as a skill:

Despite some doubts about their usefulness, Burgess himself capitalised on the popularity of creative writing courses at US colleges, teaching at several, including Columbia and Princeton (Burgess pictured here at Princeton).

I was thus especially interested in viewing a seminar transcript held in the archives of the Burgess Foundation. Evidence within the transcript suggests it is a record of one of the classes on creative writing which Burgess taught at City College, New York, in 1972. The typescript provides a fascinating counterpart to the recordings which I have been cataloguing as part of the ‘Anthony Burgess on Tape’ project, which include public lectures on subjects such as ‘Modern Literature’ and ‘Utopias and Cacotopias’. The seminar transcript offers a tantalising glimpse into both Burgess’s teaching and writing practice, and his delivery appears spontaneous in comparison to the meticulous structure and careful rehearsal which undergirds his public lectures. Speaking to a student audience, Burgess adopts a conspiratorial, candid tone throughout the seminar, whose purpose is to ‘tell […] you something about the smaller details of the sense of bedevilment – the sense of frustration which accompanies the working and creative art like novel writing’. Throughout the session, Burgess likens novel writing to ‘practicing a useful craft’, and his advice to the class of aspiring writers is simultaneously pragmatic and wrought with artistic conviction. Students are told to ‘Never accept an advance if you can possibly avoid it because once you have accepted the advance you will not be willing to write the novel’, a suggestion which gains particular significance in light of Burgess’s historically shrewd relationship to his publishers. However, Burgess ultimately foregrounds the psychological labour of writing:

Writing a novel is a very full-time job because you have got to live in the ambience, you have got to live with the characters. There is always the danger that if you break off for some new purpose, when you return to the novel, the experiences you have had will modify its shape but it will not be the novel you began to write.

For Burgess, the desire to write fiction comes to appear inevitable. There is labour involved, certainly, but there is an urgency and sincerity to his pursuit of this creative impulse which is inescapable. It was work to which he was compelled to return throughout his lifetime. We can see this desire remains undimmed when Burgess concludes his conversation with Michael Schmidt for the BBC Radio 3 Programme Third Ear in March 1989. For Burgess, writing fiction is as difficult as ever, but its necessity – to contribute to the making of meaning, and the mastery of language – remains:

Milena Schwab-Graham is a PhD Student at the University of Leeds. Her research is funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council through the White Rose College of the Arts and Humanities. Read her previous blog post here.