Did Anthony Burgess hate the American ending of A Clockwork Orange?

-

Will Carr

- 4th March 2021

-

category

- Blog Posts

Clockwork Controversy:

Myth: Anthony Burgess disliked the American ending of his novel, which omitted his final chapter.

Fact: Burgess was unsure about how to end his novel from the beginning. He liked the American ending and authorised its publication. It was only later in life that he preferred the British ending.

Anthony Burgess’s 1961 manuscript of A Clockwork Orange has a handwritten note at the foot of the twentieth chapter:

‘Should we end here? An optional “epilogue” follows.’

This ‘epilogue’ was published in the first British edition of the novel as the twenty-first chapter.

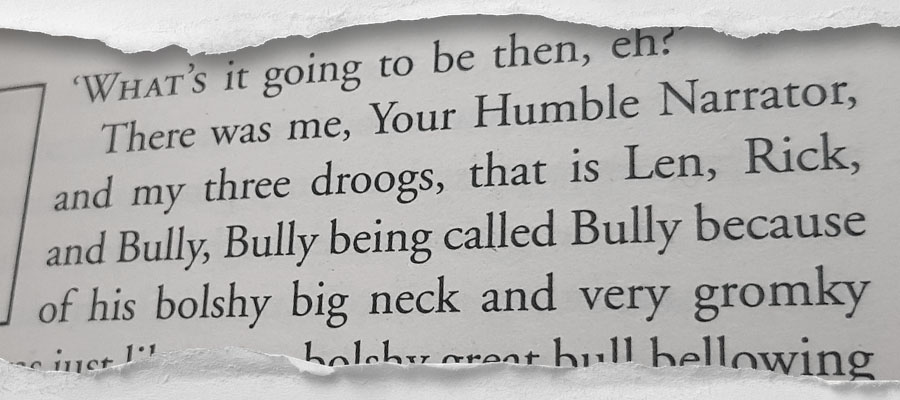

In this final chapter Alex, abruptly and surprisingly, grows up. Although he is still only eighteen, he says that he wishes to get married and have a baby. He even carries a picture of a small child in his wallet. His musical tastes also change: he now prefers the softer music of Lieder to the banging and crashing of Beethoven’s symphonies. And he decides that he has outgrown his life of crime. This change of heart in the final chapter dramatically alters the meaning of the novel.

Explore the music of A Clockwork Orange, including “the old Ludwig van”.

In 1963 the American publishers W.W. Norton released a shorter version of A Clockwork Orange which omitted the final chapter. In this version, Alex is left unreformed, ‘carving the whole litso of the creeching world with my britva.’ The book ends with the words: ‘I was cured all right.’

The authority for this editorial decision came from Burgess himself, who discussed the ending in an exchange of letters with his American editor. He agreed with the suggestion that the dropping of the final chapter made for a more convincing ending. Much later, in the 1980s, Burgess claimed that he had been put under pressure to change the structure of the book, but it is clear that he approved the decision to cut the final chapter in 1963.

It was the shorter novel, with the darker ending of chapter 20, which became widely known when Stanley Kubrick followed it in his film adaptation in 1971. What is less well known is that Burgess himself had written an earlier film script in 1966, and in this version of the story he also leaves out the twenty-first chapter.

The ambivalence Burgess felt about the ending of A Clockwork Orange appeared many times in interviews and articles. Speaking to the Paris Review in 1973, he said that he ‘gave in a little too weakly’ to the suggestion that his final chapter should be removed. However, in the same interview he states that he had been persuaded by critics that the ‘American’ ending was stronger. He added: ‘I’m not able to judge for myself now as to whether I was right or wrong.’

It was not until 1986 that the twenty-first chapter was published in the United States. Burgess wrote in his introduction to the new Norton edition:

Readers of the twenty-first chapter must decide for themselves whether it enhances the book they presumably know or is really a discardable limb. I meant the book to end in this way, but my aesthetic judgments may have been faulty.

Many of Burgess’s marginal notes included drawings. Find out more.

Ultimately, Burgess abdicated responsibility for any authoritative ending for his novel, and it is up to readers to decide which conclusion they prefer. Perhaps this is appropriate in a book which deals with the importance of free will, moral choice, and individual responsibility.

The ‘Clockwork Controversies’ series, in which we examine myths surrounding Anthony Burgess’s most famous book, is one of several ways in which the Burgess Foundation is marking the 50th anniversary of Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation of A Clockwork Orange.

Find out more about the creation, meaning and legacy of Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange elsewhere on our site.