How to read Earthly Powers

-

Andrew Biswell

- 14th May 2020

-

category

- Blog Posts

Andrew Biswell: How to read Earthly Powers

‘The ideal reader of my books,’ Anthony Burgess told John Cullinan of the Paris Review in 1973, ‘is a lapsed Catholic and failed musician, short-sighted, colour-blind, auditorily biased, who has read the books that I have read. He should also be about my age.’

Readers who lack those very specific qualifications might occasionally scratch their heads when they encounter neologisms and allusions in Burgess’s writing. The best way to read his work is probably not to worry too much about ‘difficulty’, and simply to immerse yourself in the characters and story.

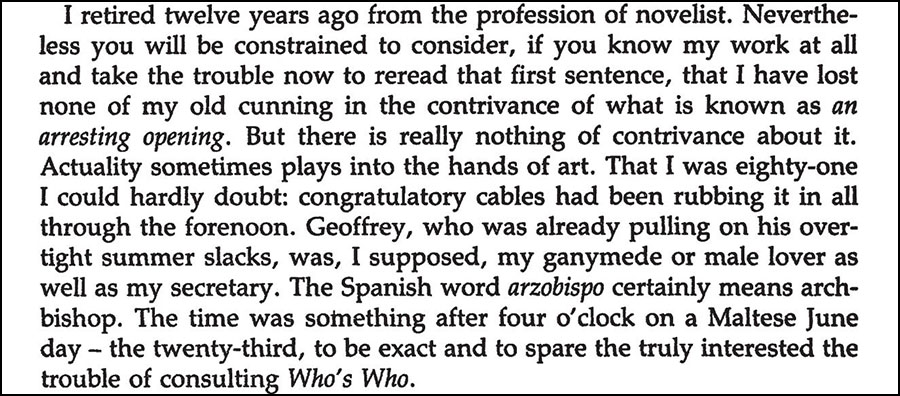

Earthly Powers (first page excerpt pictured above) is Burgess’s longest and richest novel, and it is likely that the linguistic exuberance of the text has defeated a few readers before now. Burgess himself was aware that some people were resistant to the more challenging elements of his prose style.

Earthly Powers (first page excerpt pictured above) is Burgess’s longest and richest novel, and it is likely that the linguistic exuberance of the text has defeated a few readers before now. Burgess himself was aware that some people were resistant to the more challenging elements of his prose style.

When John Cullinan asked him to speculate about why his novels were not more widely known, he replied: ‘It’s because the vocabulary is too big, and people don’t like using dictionaries.’

Burgess gives us some hints on how to read Earthly Powers in the second volume of his autobiography, You’ve Had Your Time, published in 1990:

‘Write a long novel today — one, say, of 650 printed pages — and you have to erect a scaffolding in advance of setting down the first word … The number of chapters I proposed [in Earthly Powers] matched the number of years of the man telling the story. He celebrates his eighty-first birthday in the first chapter: let then the total of chapters be eighty-one. 81 is 3 X 3 X 3 X 3. I spelt this out at the beginning. “I looked at the gilt Maltese clock on the wall of the stairwell. It said nearly three … We were three steps from the bottom … I minced the three treads down to the hall … Three steps away lay a fresh batch of felicitations brought by Cable and Wireless motor cyclists.” It was only when the proofs came from the printer that I saw that I had miscounted; there are eighty-two chapters’ (p. 356).

This suggests that the reader should look out for significant repetitions in the text. Elsewhere in his autobiography, Burgess suggests that Earthly Powers was not always understood by its translators. He writes: ‘A lot of translations have to be rejected as inept. In a late novel of mine, Earthly Powers, the injunction “Go to Malaya and write about planters going down with DTs” was rendered into Italian to the effect of writing about planters committing fellatio with doctors of theology.’ The confusion arose partly because the translator did not recognise ‘the DTs’ as a slang abbreviation of ‘delirium tremens’, which is one of the symptoms of alcoholism. Fortunately, Liana Burgess found the mistake and made sure it was corrected before publication, preventing a hair-raising misapprehension among the novel’s Italian readers.

When I read Earthly Powers for the first time more than 30 years ago, I can remember being intrigued by a number of unfamiliar words scattered throughout the text. I found this baffling and exciting at the same time: the novel seemed to open up a world that was bigger than the one I knew. I made a list, quite a long list, of things I didn’t understand, intending to look them up later. I was puzzled by out-of-the-way terms such as ‘beneficent numen’, ‘finocchio’, ‘mephitic hogo’, ‘quincunque vult’, ‘labian strabismus’ and ‘autocephalic’ — words and phrases which hadn’t previously formed part of my experience, and whose meaning could not readily be guessed at.

When I read Earthly Powers for the first time more than 30 years ago, I can remember being intrigued by a number of unfamiliar words scattered throughout the text. I found this baffling and exciting at the same time: the novel seemed to open up a world that was bigger than the one I knew. I made a list, quite a long list, of things I didn’t understand, intending to look them up later. I was puzzled by out-of-the-way terms such as ‘beneficent numen’, ‘finocchio’, ‘mephitic hogo’, ‘quincunque vult’, ‘labian strabismus’ and ‘autocephalic’ — words and phrases which hadn’t previously formed part of my experience, and whose meaning could not readily be guessed at.

I soon discovered that some of the terms on my list were not in the dictionary, either because they were foreign loan-words (from Italian, Ancient Greek, Latin or Malay), or because they were neologisms of Burgess’s own devising. Everything in the book turns out to be meaningful, and perhaps every reader needs help of one kind or another to work it all out.

In recent years, there has been a growing emphasis on annotating Burgess’s texts. The majority of this work has been undertaken by the editors of the Iwell Edition, which has been publishing new titles since 2017. As there is no immediate prospect of an Irwell Edition of Earthly Powers, partly because the resulting volume would be at least a thousand pages long, readers have remained in the dark about many of its mysteries.

As part of the Burgess Foundation’s project to celebrate the fortieth anniversary of Earthly Powers, we have launched a new online annotation project in the form of a Wiki. We hope that this open-access resource will act as a companion for anyone who would like to have obscure words defined, or translations of terms taken from other languages.

The Wiki provides biographical information on real-life places and people (such as Radclyffe Hall or Ford Madox Ford) which appear in the text. It contains information about quotations, allusions and other obscurities. The Wiki also reveals a number of private references: for example, the mysterious ‘Dr Belmont’, who looks after Hortense during her pregnancy, alludes to a real person called Georges Belmont, one of Burgess’s French translators, who became a close friend.

The other purpose of the Wiki is to draw attention to relevant pieces of writing in the Burgess canon. For example, an unidentified quotation from Walt Whitman in Chapter 5 is glossed with a note about ‘The Answerer’, Burgess’s essay on Whitman, which first appeared in the Spectator on 25 March 1966, and was later reprinted in Urgent Copy, his book of literary essays. Another note on Ernest Hemingway (who appears as a character in the novel) points the reader to Burgess’s biographical book about Hemingway, which he published in 1978, not long before he finished writing Earthly Powers. To help readers find their way through the novel and the annotations, the Wiki is fully searchable.

Launched in April 2020, the Earthly Powers Wiki is currently in its infancy. We are inviting contributions from readers who would like to help us solve some of the puzzles in Burgess’s text. To ensure consistency of style, contributions to the Wiki are moderated by staff at the Burgess Foundation.

Find out more about the #EarthlyPowers40 project here.