Enjoying William Walton

The performances of William Walton’s Façade at the Burgess Foundation on 18 March have prompted us to look into the archive for writing by Burgess about Walton’s music.

William Walton (1902-1983) was one of Burgess’s favourite English composers, and his interest in Walton’s film music for Laurence Olivier’s Henry V is evidenced by a copy of the printed score among Burgess’s books. The strong influence of Walton on Burgess’s ballet about the life of Shakespeare, Mr WS, has been noted by various commentators.

In an article titled ‘Enjoying Walton’, published in the Listener on 6 June 1968, Burgess wrote that Walton was ‘the composer who has meant more to some of us than anyone since Stravinsky.’

In the article, Burgess describes his own early-morning routine, which involved drinking a Bloody Mary, eating a raspberry yoghurt and listening to ‘loud gramophone music’ while preparing to begin ‘the daily damnation of writing.’ Two of the records he liked to play at this time of day were Walton’s Portsmouth Point overture and the Crown Imperial march. Walton, Burgess said, was superior to modern composers such as Cage, Boulez and Stockhausen because of the ‘cold-shower impact’ of his ‘diatonic dissonance and Chianti-rough orchestration.’

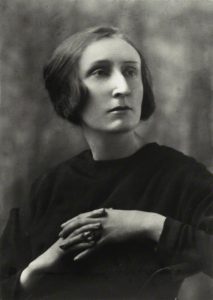

Burgess also considered that Walton had been fortunate in his choice of poets and librettists. Whereas Elgar had set texts by obscure or minor poets (including his own wife, Caroline) in Sea Pictures, Walton had worked with Sacheverell Sitwell on Belshazzar’s Feast and Edith Sitwell on Façade. (Sacheverell Sitwell also contributed the text to Constant Lambert’s Rio Grande, which immediately joined Burgess’s canon of modern masterpieces when he heard the first performance at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester at the age of 12.) The importance of Walton lay in the fact that he had benefited from ‘the releasing quality of the Sitwell imagination,’ which had allowed him to unite words and music more successfully than any of his contemporaries.

Speaking of a televised performance of the ‘Popular Song’ from Façade, Burgess complained that the BBC had chosen to broadcast the orchestral version, omitting the words, thus demonstrating that ‘without the Sitwell words, Façade is only half-alive.’ He continued: ‘As for the Façade items recited by Peter Pears and Cleo Lane, these were not quite right, either. The work was intended for speakers (Constant Lambert did a good recording with Edith Sitwell) and not for singers who have temporarily cut out voice.’

Summing up the importance of Walton, Burgess wrote: ‘our music is chiefly an extension of our literature, and that extension comes from the area of feeling, not of form. Without literature, Britten would have only an arpeggio of a 13th to exhibit.’

It is clear that Burgess’s admiration for Edith Sitwell’s poetry was also very high. Quoting from the ‘Sir Beelzebub’ song (a poem from Façade that he had memorized in his youth), Burgess writes in his musical autobiography, This Man and Music (1982): ‘In writing surrealistic verse to be accompanied by the highly structured musical rhythms of William Walton, Edith Sitwell played with the principle of discontinuous narrative […] Things happen here because of free association, helped with rhymes.’

A further nod to Walton may be seen in the German translation of Any Old Iron. Readers will remember that, early on in the book, some of the characters attend a performance of Walton’s famous oratorio Belshazzar’s Feast in Manchester in 1939. Many readers will be unaware that the German edition of this novel is retitled Belsazars Gastmahl (or Belshazzar’s Feast). It is not clear who took the decision to change the title of this 1996 translation, published three years after Burgess’s death, but it is likely that Liana Burgess, Anthony’s widow, would have been asked to approve it.

Walton’s Façade will be performed along with the premiere of a newly commissioned work by Daniel Kidane, at 6:00pm and 8:00pm, at the Anthony Burgess Foundation, Chorlton Mill, 3 Cambridge Street, Manchester M1 5BY.