Honey for the Bears: the novel and its critics

-

Andrew Biswell

- 24th September 2013

-

category

- Blog Posts

Honey for the Bears, first published in 1963 and recently reprinted by Norton in New York, is one of Anthony Burgess’s strangest works of fiction. This Anglo-Russian comedy follows its protagonists – an English antique dealer named Paul Hussey and his errant wife, Belinda – on a sea voyage to Leningrad (now St Petersburg) in Soviet Russia, where they become embroiled with black marketeers, secret policemen and political dissidents. As in A Clockwork Orange, published the previous year, Burgess uses a Russian backdrop as a way of exploring his long-standing preoccupations, including free will, the problems of cultural and linguistic mistranslation, and the difficulties arising from uninhibited sexual congress.

After an eventful sea voyage during which they meet the ambiguous man/woman Dr Tiresias (a character who seems to have walked out of Ovid’s Metamorphoses or ‘The Waste Land’ by T.S. Eliot), Paul and Belinda arrive in Leningrad. At first they are shocked to find that the Soviet Union is ‘coloured like anywhere else; it was not just grey, as in spy films.’

As the couple are leaving an expensive restaurant, they encounter a gang of Clockwork Orange-style teenage thugs, known in Russian as stilyagi: ‘Young toughs in shirt-sleeves […] armed with coshes and bottles, they politely made way for the leaving party, waiting for the doors to be bolted again, then resumed their batterings and yells. Something to do with the chess-mind. “Where are the police?” asked Paul. There seemed altogether too much freedom in the Soviet Union – no licensing laws, teddy-boys rampant and unreproved, and now a raincoated prostitute under a dim lamp.’

Belinda, who has been unwell during the voyage, develops a rash, ‘burning purple, the texture of porridge,’ and is taken to hospital, where she strikes up a close friendship with a Soviet nurse. Meanwhile Paul wanders the streets of Leningrad alone, falls into the company of criminals, loses his false teeth in a fight (‘“You beaftly fwinifh fadift,” said Paul’), and makes some discoveries about his own sexual inclinations. Unexpectedly, he becomes involved in a plot to smuggle the son of a dissident composer out of Russia.

Jocelyn Brooke in the Listener (27 March 1963) described the novel as ‘one of the most convincing evocations of contemporary Russia that I have read.’ He added that ‘Nobody else – with the possible exception of [T.S.] Eliot, could have got away so neatly with the unacknowledged quotation from Hopkins on page 86.’

The anonymous reviewer in the Times Literary Supplement made comparisons between Burgess and Jonathan Swift when discussing the novel’s savage indignation at the absurdity of the modern world. ‘It is possible, in fact, that Mr Burgess is writing too much too quickly, and that a more disciplined savagery would be even more effective, but this is perhaps a small price to pay for such vitality and inventiveness. Certainly it is long past time that critics stopped comparing Mr Burgess, as they still do, with Evelyn Waugh and others […] and saw him as a very considerable novelist in his own right.’

The most disapproving voice – but apparently the only negative one – was that of Oleg Ivsky in the Library Journal (1 February 1964). He wrote: ‘The plot and situations of this alleged satire are silly but not funny (unless broken teeth, police tortures, and homosexuality are funny per se); background and atmosphere are as hopelessly mixed up as are all the characters, their motivations, and sexes (all five of the sexes). Particularly obnoxious are the constant parading of Mr Burgess’s nauseating brand of pidgin Russian and the habitual use of presumably authentic but barely intelligible RAF [Royal Air Force] slang spiced with a pathetic imitation of beat talk.’ Since one of the main characters has served in the RAF during the Second World War, it would be surprising if his speech contained no traces of forces slang. And Ivsky’s reference to ‘all five of the sexes’ is a bit enigmatic.

More positively, Charles Alva Hoyt wrote in the Saturday Review (29 February 1964) that Honey for the Bears was ‘One of the best-planned and most brilliantly executed books I have seen in a long time. The reader will have to admit that he is in the presence of a virtuoso.’ John Gross, reviewing the novel in the Washington Post (9 February 1964), characterised it as ‘a highly entertaining and intelligent book.’

One of the most sympathetic reviews came from Kingsley Amis (whose novels, from Lucky Jim to Difficulties With Girls, were greatly admired by Burgess), writing in the New York Times on 2 February 1964: ‘No doubt plenty of smut-hounds will be ready to denounce this book as obscene; it isn’t. There’s a vulgar error which confuses the use of sexual deviation and suchlike as (comic) material and its glorification for the purposes of shock, pornography and so on. Mr Burgess’s witty astringency – or, if you like, simply his sense of humor – makes his account of these matters chastening, deglamorizing.’ The review concluded: ‘There are so few genuinely entertaining novels around that we ought to cheer whenever one turns up. Honey for the Bears is a triumph.’

Nearly fifty years later, Amis’s emphasis on the ‘shock’ of a novel which discusses same-sex relationships seems quaintly over-stated, but it demonstrates how much anxiety about the censorship of so-called obscene publications was still in the air in the early 1960s. Not long after this review was published, Burgess appeared at Marlborough Street Magistrates’ Court in London, giving evidence in defence of Hubert Selby’s scandalous novel, Last Exit to Brooklyn, which had been prosecuted under section 2 of the 1959 Obscene Publications Act. The publishers were found guilty, but the judgement was later overturned in the Court of Appeal.

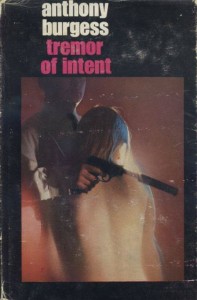

Burgess returned to the subject of the Cold War in a subsequent novel, Tremor of Intent (1966), his first work of espionage fiction, which was written in imitation of the works of John Le Carré and the James Bond novels by Ian Fleming. As Burgess’s letters to his London publisher make clear, he regarded Tremor of Intent as a ‘straight’ spy thriller, and he wanted this intention to be reflected in the choice of illustration on the dust jacket.

Interestingly, the Cold War novels of Fleming and Le Carré are both discussed in Burgess’s critical writing, and these essays will form the basis of future blog posts here.

Honey for the Bears is published by W.W. Norton in New York. The current editions of Tremor of Intent are published by Serpent’s Tail in the UK, and by Norton in the US. It is also available as an e-book and an i-book.