Manchester Made Me by Anthony Burgess

Burgess’s essay about the city of his birth was first published in the Manchester Evening News on 1 December 1984.

Telling Southerners that I am a Mancunian, I sometimes get the silly response ‘What did you say — a Manchurian?’ Meaning that the south of England still likes to think that Manchester is remote and barbaric. But Mancunium was a Roman town before most of the stuck-up suburbs of London were even thought of, and I can call myself a Mancuniense in modern Rome, where there is no Italian equivalent for West Ham or Ealing. It’s a proud title.

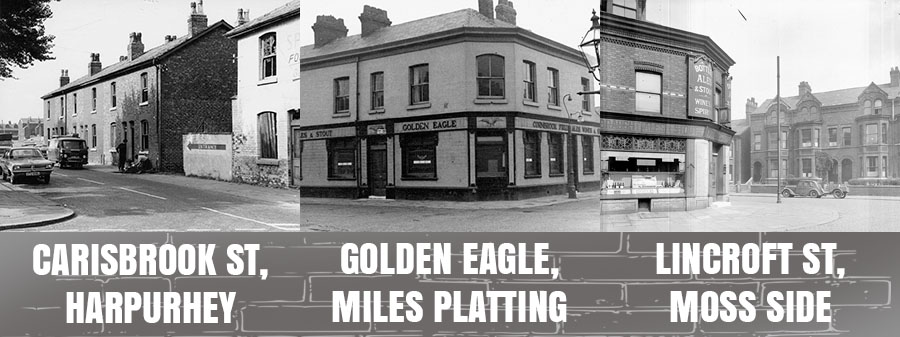

I was born in Harpurhey in 1917 and was moved to Miles Platting, Moss Side and Fallowfield before I left the city and its suburbs more or less for ever in 1940. It’s not always our fault if we desert the place that gave us our education and first love affair. The war exiled me for six years, the dying British Empire called on my services for another seven, the profession of a teacher and, later, a writer sent me further and further south.

For the last sixteen years I’ve been living out of England. We go where we have to go. St Paul was beheaded in Rome after trying to convert the pagan cities of the Near East, but he never forgot Tarsus. He called himself a citizen of ‘no mean city.’ I call myself the same, and I never forget Manchester.

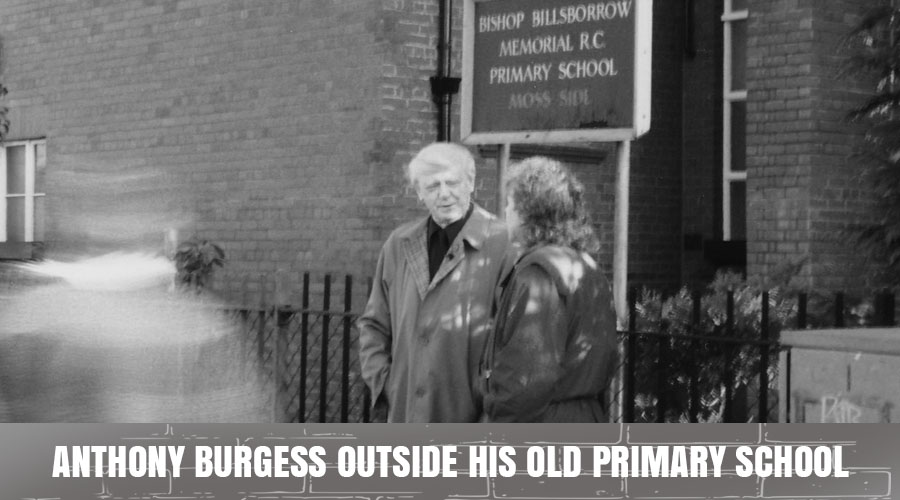

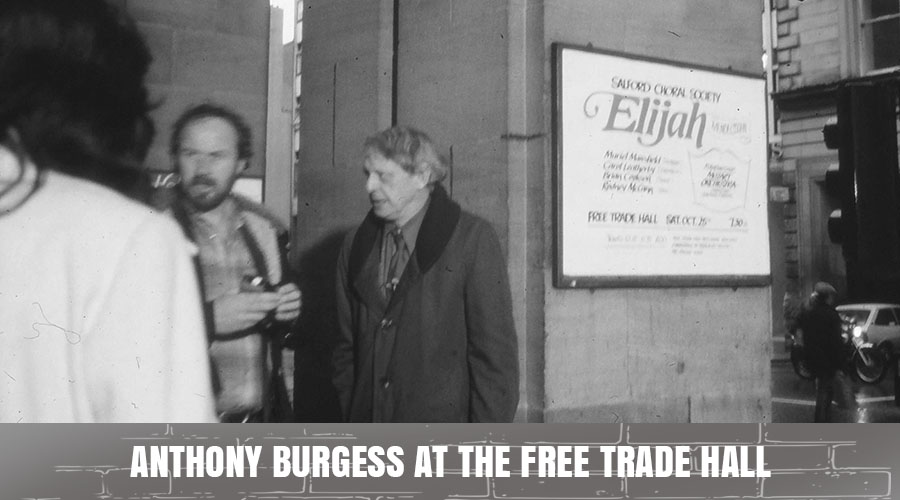

The Manchester of today is hardly at all the city of my childhood. The schools that taught me still stand — the Bishop Bilsborrow Memorial School on Princess Road and the Xaverian College in Rusholme — but the university where I graduated has ceased to be the cosy little institution which some people still called Owen’s College: it’s become a fearsome academic monster built on American lines. The Hallé Orchestra is not quite what it was in the days of Sir Hamilton Harty. When the BBC Symphony Orchestra stole the Hallé’s best players and Harty was headlined in the News and the Chronicle with his snarl ‘Amiable bandits’, the Manchester orchestra — the ‘Alley Band’, as Lord Mayor Joe Toole used to call it — was known as the finest in Europe. And it was. Hans von Richter, the great Wagnerian, had made sure of that.

It was Richter who often referred to Manchester as a ‘grosse Stadt’ — a great city that was somehow Germanic like Stuttgart or Hamburg. It was tough and masculine and very northern. It was Cottonopolis, the world centre of a trade imposed on Lancashire by its climate: cotton preferred to be spun in the damp. Manchester was humid and still is, but its reputation for rain was always much exaggerated. It was a city that looked better in the rain than in the dry — grim, sooty, somewhat depressing.

Manchester was masculine in not being greatly impressed by beauty. There was always a puritanical strain in the hard-headed fathers of commerce who ran it. Beauty was not serious, but business was. The beauty of Beethoven or Mozart was permissible every Thursday evening in the season; fine pictures were in order so long as they were shut away in a municipal gallery. Buildings like the Town Hall and the Central Library and the University itself could be imposing, but they ought not to be seductive. Manchester was not Italy. Its architecture was proud to wear a coat of soot.

But there were enough foreigners in Manchester to temper the spirit of the hard-headed north. The girl I first fell in love with was Italian; the second was Jewish and German. When Hitler began his pogroms, Manchester was one of the first British cities to welcome an influx of German refugees. It is a cosmopolitan city still, with its African and Arab banks, but so are all British towns these days. Before the war it was selectively cosmopolitan in that it was European. In many ways it was a kind of outlying centre of Europe, foretelling the future of a whole continent. Here industrialism began, and a railway system, and Marx and Engels (who was by way of being a Mancunian himself) surveyed the excesses of capitalism before writing books that changed the world.

The Manchester of my youth grimly clanged with trams and shrilled with factory hooters. But you could always get away from the noise of hard work by going to Platt Fields or Victoria Park or out to Boggart Hole Clough. The city fathers made sure we had plenty of green. When night fell there was always plenty of entertainment. My mother used to sing and dance, before the First World War, in music halls where audiences used their hands mostly for sitting on or hurling rotten eggs, rarely for indiscriminate applause.

If you could succeed in a Manchester theatre, then you would have no difficulty further south, where, in the Mancunian view, audiences were soft and stupidly uncritical. C.B. Cochran used to preview his shows at the Manchester Opera House, not trusting the first reactions of Londoners. Noël Coward was a sporadically well-known figure in Manchester. The French restaurant in the Midland Hotel was good enough, and still is, for the cream of the international theatrical and musical worlds.

But I remember Manchester’s home-grown theatre. While Shaftesbury Avenue weakly grinned or stupidly guffawed at silly social comedies, Miss Horniman at the old Gaiety helped to found a Manchester drama which learned from dangerous Ibsen up in Oslo: what London sneered at as provincial theatre was really daringly international. Ireland and Lancashire together are said to have breathed new life into a decadent art. But the Abbey Theatre in Dublin had to learn from Manchester. There was, besides the Gaiety, a fine repertory theatre in Rusholme: here Wendy Hiller and Robert Donat began their careers. There was even a Manchester film company whose chief asset was George Formby Junior. The strength of the Manchester dramatic pulse is still to be seen in the twice-weekly Coronation Street, which dourly glorifies, to the routine pleasure of millions, the kind of life which this Mancunian knew as a boy.

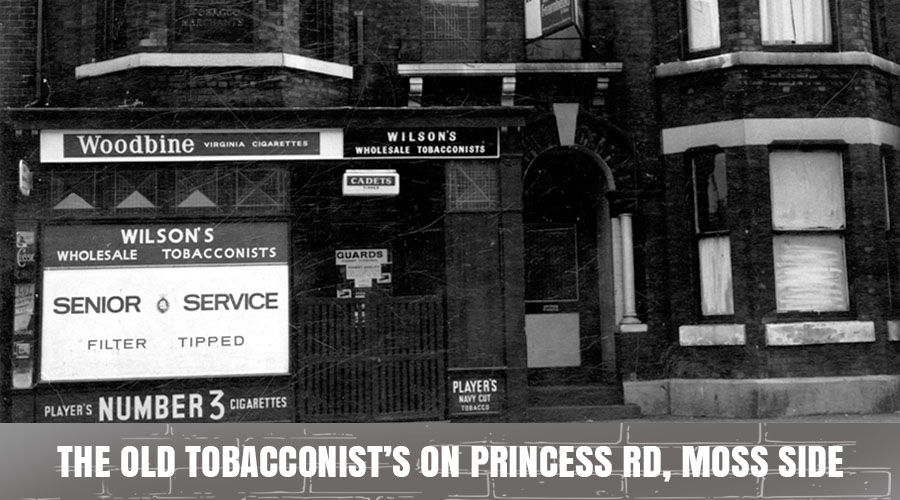

My family was not poor, though it settled in poor districts. It was a Catholic family with a strong Irish admixture determined to make good through selling two of the chief solaces of life — drink and tobacco. I lived over a tobacconist’s shop on Princess Road, Moss Side, and it still stands. Then I lived over an off-licence on Moss Lane East in the same suburb, at the corner of Lincroft Street. Things change. I saw decay which was, in time, arrested and even reversed, but my childhood among tenements and trees chopped down for firewood was not a bad one.

The time when I was a student at the University was perhaps the happiest of my life. I had little money, but beer was sixpence a pint in the saloon bar, and you could buy twenty Player’s for a shilling. I loved the pubs, which were gamy, even Rabelaisian, and I earned extra money by playing the piano in them. My father played the piano in a cinema before the talking pictures came; my mother, before the post-war influenza epidemic took her and my sister, had sung and danced professionally — there was always in our family the capacity to entertain.

I loved the fish and chip shops — there has been nothing like them since those days — and the United Cattle Product restaurants which served tripe and cowheel. I loved Lancashire hotpot, meat and potato pie, potato cakes and Eccles cakes. Now the Manchester cuisine seems to be all tandoori curries and pizzas. The cosmopolitan impulse seems to have gone too far. Manchester was more important when it was more provincial.

I don’t think I’m being chauvinistic when I say that the Manchester Guardian was once the best daily newspaper in the world. Something went out of it when it turned itself into the Guardian. It was the paper in which I first published at the age of twelve — not prose or verse but a cartoon for which I was paid five pounds (big money in 1929) — and I was right to be proud. It was something to be a young citizen of a town which had the best orchestra and the best newspaper, and whose university had the best history department in the world (under the great L.B. Namier). For that matter, Tommy Duck’s was the best pub in England, the Gaumont Long Bar was the longest, and Belle Vue had the best zoo. And, by heavens, Manchester, an inland city, had turned itself into a port: ‘Manchester Goods for Manchester Docks’ was in all the trams.

I call myself a Mancunian, which I have every right to do, but I wonder how far I am recognisable as a Manchester man. The accent had to go, at least in southern company, but I still use words like mard and nesh and deg at home, where I also affirm with a loud aye. Sometimes love comes out with the wrong vowel (that southern vowel is damnably hard for us northerners to learn) and I often take a bath with a short a. The best jokes still seem to me to be Lancastrian (the man who had eaten a packet of crisps for the first time said: ‘That blue one were a salty bugger’), and the best members of my family are all buried in Moston Cemetery (death itself is a fine Manchester joke).

I still have a tribute to pay to my city — a novel [Any Old Iron] which presents it as it was before the Germans knocked hell out of it — but I can only return to it in the spirit. Manchester has changed in its own way, I have changed in mine, and our only point of contact lies in the past. It was a fine past while it lasted. I can speak of the present only as a shy visitor. But if the Manchester of the future becomes again the great city it used to be, then I shall be the first to be proud.