Inside the archive: Anthony Burgess and his typewriters

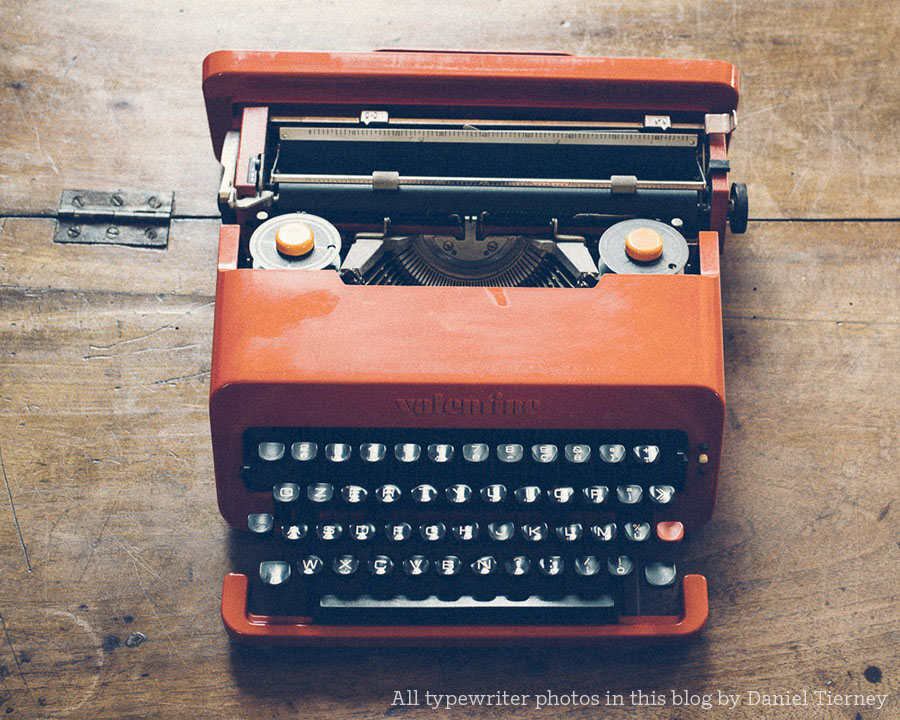

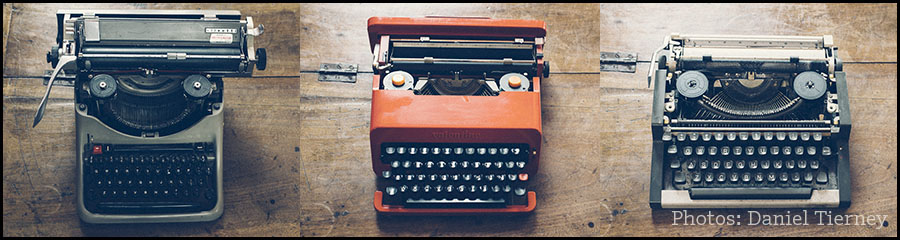

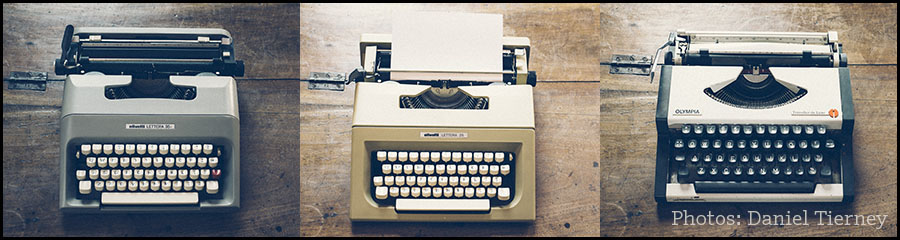

Of the hundreds of objects belonging to Burgess in the Foundation’s archive, there are some which, more or less without fail, are guaranteed to evoke an immediate response from visitors — none more so than Anthony Burgess’s typewriters, some of which are on display in the reading room.

Burgess had a particularly close association with certain objects: cartoonists and photographers rarely captured him without a cigar or a typewriter, and he wrote about his fondness for both. We have covered his smoking paraphernalia before, especially his matchbooks, but his typewriters deserve closer inspection.

Burgess briefly, and reluctantly, experimented with a word processor towards the end of his life, so most of the books, articles, and essays he wrote were created on a typewriter.

Burgess gives two main reasons for his preference.

Firstly, he believed in the authentic labour inherent in writing. Book-writing, he wrote in Urgent Copy, is ‘hard on the brain and excruciating to the body’, and the manual typewriter was his tool of choice, at least as a novelist and a journalist. When composing music, he preferred to use a pen. Recalling the experience of writing his early novels in Malaya, he describes sweat dripping down his face and occasionally landing on the page. Writing, for Burgess, was a physical activity, with a good deal of muscular effort involved.

The second reason stems from his belief that the typewriter improved the quality of writing by promoting greater discipline, and by encouraging a writer to consider the sounds of the written word.

In an interview recorded in 1987, Burgess spoke about his word processor: ‘This is a dangerous apparatus, because you tend to be very careless. You tend to write something, because you know anything will do, because you can correct it. But if you are writing on the typewriter, you tend to get the sentence in your head first as a piece of music. Does it sound all right? Is it good? I think the word processor will ruin prose in time. I think it already is.’

He echoed this sentiment in an article titled ‘Struggles with a Word Processor’, written in 1988:

There is a lack of blacksmith muscle in the tapping of the console … Using a typewriter, foreseeing the flaky mess of Tippex or the ugliness of XXXXXXing a mistake out, there is a tendency to frame a sentence in one’s head before committing it to the tapping fingers. In other words you hear a phrase in your ears before converting it to ocular graphemes. What the word processor is doing is to kill the auditory, all writing becomes a matter for the eye.

The typescripts of Burgess’s journalism and novels have very few corrections, perhaps as a result of his careful deliberation before committing words to the page. He took pride in the clarity of his copy, as is reflected in the following extract from another home recording. During a pause in Burgess and Liana’s reading of his verse translation of Alexander Griboyedov’s play Chatsky, Burgess remarks: ‘Acts 1 and 2 I did in rough first and copied out. This [Act 3] I did straight onto the typewriter. Quite an achievement. That explains why the style is maybe a bit different.’

Burgess’s affection for the typewriter as a means of writing did not result in him being particularly precious about the machines he owned. They were functional objects to be used and discarded, if they could no longer be repaired. As he writes in Homage to Qwert Yuiop:

I have earned my living with a typewriter … and I have developed an affection for the instrument analogous to my love for my old Gaveau piano, which once belonged to Josephine Baker. But whereas a piano, once acquired, becomes a permanent article of furniture, typewriters break down irreparably and have to be replaced. Yet the old beloved name — Qwert Yuiop — reappears and proclaims a continuity of identity, minimally modified when it gets into France and becomes Qzert Yuiop. Without Qwert Yuiop’s willingness to submit to my punishing fingers I doubt I could have sustained the profession of author.

The archive contains a dozen typewriters which belonged to Burgess, most of which are portable and no longer in working order. Olivetti was clearly his favoured brand, but there are other models made by Olympia. Sadly, in the majority of cases, it’s not known which typewriters were used to write which novels, but a close analysis of original typescripts may reveal further information.

Although Burgess preferred to use a typewriter himself, he acknowledged that its days were numbered. In an essay predicting what life would be like in 2020, he suggested that the nature of writing would have changed beyond recognition and ‘the electronic word processor’ would become the dominant technology of literary production.

Still, the clatter of the typewriter rings loud throughout Anthony Burgess’s life. If you listen carefully, Burgess can be heard typing in the background to the following recording of Liana playing the piano.