Inside the archive: Five fascinating objects owned by Anthony Burgess — and what he wrote about them

-

Anna Edwards

- 26th May 2020

-

category

- Blog Posts

One of the most fascinating, yet underexplored, areas of the Burgess Foundation’s archive is its object collection.

The collection consists of furniture, musical instruments, typewriters, crockery, glassware, awards, artwork, ornaments, and other collectibles that belonged to Burgess and his family and were gathered throughout their travels in Europe, Malaysia, and America.

Many individual pieces are interesting in their own right, such as a clay bust of Burgess, sculpted by his friend and neighbour Milton Hebald (1917-2015) in 1970, or an eighteenth century English guitar that Burgess bought at auction in 1987.

Taken as a whole, the collection offers an unrivalled opportunity to engage with the material culture with which Burgess and his family surrounded themselves and interacted.

Like many writers, Burgess inserted objects from his real life into his fiction, using them in a variety of ways, to help move plot forward, or to develop character, conflict, or imagery. Although it would be a mistake to think that any of Burgess’s fictional characters speak directly for their creator, knowing that many of the things they mention and experience have real-world counterparts provides a sense of solidity and can imbue objects with new levels of meaning and significance.

Read on for five objects in our archive with fictional counterparts.

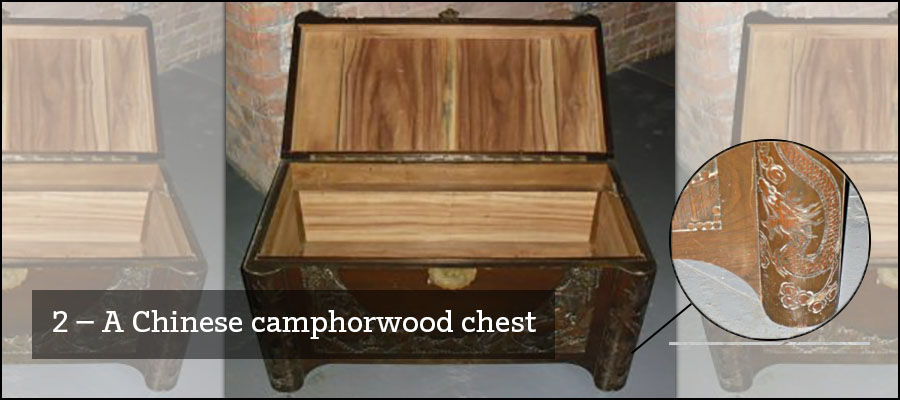

1 — A collection of matchbooks

Burgess was a life-long and heavy smoker and the archive contains many pieces of smoking paraphernalia, including tins of cigars, ashtrays and matchbooks.

Bowls of pocket-sized matchbooks were a regular fixture in restaurants, bars, cocktail lounges, and hotels for much of the twentieth century, found on tables, by tills, and in guest bedrooms. The design was simple – 2 rows of flexible cardboard matches attached to a paper folder – but the colourful cover, often emblazoned with a company logo, made these books an effective advertising tool and companies were keen to make them freely available to their customers.

For their users, beyond their intended practical use, matchbooks served as souvenirs, keepsakes of travels or mementos of memorable evenings. Kenneth Toomey, the narrator of Burgess’s Earthly Powers (1980), conveys this sentiment in the following extract:

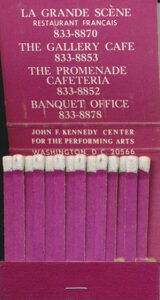

‘I took a cigarette for myself from the Florentine leatherbound box on the counter. There was also a huge wooden bowl from Central Africa full of matchbooks, trophies of the world’s airlines and hotels. I had toyed once with the notion of a travel book arranged on the aleatory taking out of matchbooks from this bowl, rather like filthy Norman Douglas’s autobiography based on the random selection of visiting cards. It had come to nothing. There is sense, however, in keeping a bowl full of such trophies: there are addresses and telephone numbers there, as well as a palpable record of travel helpful to an old man’s memory. I lighted my cigarette with a match from La Grande Scène, a restaurant at the top of the Kennedy Center in Washington, 833-8870. I could not for the life of me remember having been there. I puffed and shortened my life.’

Burgess’s own collection of matchbooks, extending to many hundred items, includes one from La Grande Scène (pictured here). Three matches are missing.

Visit our Object of the Week series for a very familiar image of Anthony Burgess: the smoker.

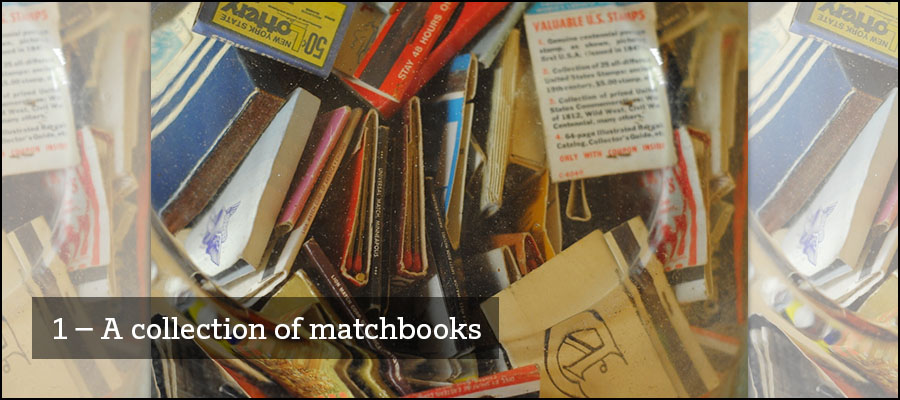

2 – A Chinese camphorwood chest

In One Hand Clapping (1961), Burgess’s comic satire on consumer culture, the protagonist Janet Shirley and her lover Redvers Glass use a camphorwood chest, similar to that owned by Burgess, to dispose of a body:

‘[Redvers Glass] said: “That shop in Rue What’s-its-name. Where they have the antiques and things.”

“Yes?”

“They have a Chinese camphorwood chest. A nice big one. Camphor will preserve anything. A lovely smell, too. We’ll go and buy that.”

“All right,” [Janet] said.

So we went to this shop and Red spoke in French to the old man who ran the place. This chest was a nicely carved big box, all covered with dragons, very cleverly done. It was very big, too, as big as my trunk…’

3 — A box of house keys

Between the time Burgess returned from his service in Gibraltar during the war and his death in 1993, he had over 16 different residences. To this list of (semi) permanent addresses can be added shorter stays in temporary accommodation as part of frequent book and lecture tours throughout Europe, America, Australia and New Zealand.

Burgess’s peripatetic lifestyle influenced his writing heavily and is itself documented in a box full of house keys that survives in the archive. The earliest identifiable key in the collection comes from 168 Triq il-Kbira (or Main Street) in Lija, Malta, where Burgess moved shortly after marrying Liana Macellari in 1968, and which is one of Kenneth Toomey’s many homes in Earthly Powers.

Burgess moved from Malta to Italy in the early 1970s, first buying a house in Bracciano, a town outside Rome and the setting of the final chapter of MF (1971), and then renting a flat in Rome itself. The flat was located on the Piazza Santa Cecilia in Trastevere (key pictured) and was the model for Ronald Beard’s accommodation in Beard’s Roman Women (1976).

Burgess moved from Malta to Italy in the early 1970s, first buying a house in Bracciano, a town outside Rome and the setting of the final chapter of MF (1971), and then renting a flat in Rome itself. The flat was located on the Piazza Santa Cecilia in Trastevere (key pictured) and was the model for Ronald Beard’s accommodation in Beard’s Roman Women (1976).

Among other residences that featured in Burgess’s fiction are his home at 6 Rue des Muets in Callian, Provence, which appears in The Pianoplayers (1986):

‘There is a big laugh, only it is a bit bitter, in the name of the street in Callian where I have my little house for the summer. It is called Rue des Muets, which means Street of the Dumb, but it is the noisiest street imaginable, what with Vermicelliano and his wife and kids, and the three homo Algerians always quarrelling, and dirty too what with the big dogs leaving their crottes all over people’s doorsteps.’

The Burgess archive contains keys dating back to 1968 — see what secrets they open up here

4 — A Restoration sideboard

One of the most substantial items in Burgess’s furniture collection is a Restoration sideboard, dating from 1685.

Standing at approx. 1m 60cm in height and 1m 90cm in width, the front of the sideboard is richly decorated with a variety of carvings, including spiral designs, single lines and cross-hatching.

The provenance of the item is unclear, but Burgess had apparently acquired it by 1963 as a very similar item is described in the first novel of his Enderby series, Inside Mr Enderby, published in that year:

‘Enderby, in thinker’s pose on the lavatory seat, frowned back to an evening when he sat finishing his epithalamion in her trim dining-room, facing a piece of furniture he admired – a sideboard, massive and warped, proclaiming its date (1685) among carved lozenges and other tropes, fancies of the woodworker signifying his love of the great ship-oak he had shaped and smoothed.’

There are no photographs of the sideboard at Burgess’s house in Etchingham, where he was living in 1963, but he clearly admired the piece enough to arrange for it to be transported to Malta some years later, as this photograph in the slide collection shows. Here we see young Andrew Burgess (right) and friend in front of the sideboard.

5 — A William Foster harpsichord

Anthony Burgess’s musical instruments range from one-off novelty pieces, such as a penny whistle, maraca, and a shaker, to more substantial items, such as a Bösendorfer piano. There are also multiple recorders, flutes and oboes, used by Burgess’s son, Andrew. Two of the pieces – a harpsichord and a clavichord – date from the 1970s and were made by William Foster, a maker of musical instruments with a workshop in Lucca. The harpsichord appears in Earthly Powers (1980) and is introduced in the first chapter while Kenneth Toomey surveys his Maltese home:

‘Over there was the William Foster harpsichord, which I had bought for my former friend and secretary, Ralph, faithless, some of its middle strings broken one night in a drunken tantrum by Geoffrey.’

Geoffrey later plays ‘ensoured harmonies’ on the instrument and, in chapter 63, Toomey recalls a particularly raucous party during which his secretary, Ralph, had ‘played jazz on the harpsichord… and then tried to throw the instrument into the stairwell.’

Burgess treated his own harpsichord rather better; apart from a few scratches and signs of general wear and tear, the instrument is in a good condition.

To find out more about Burgess’s musical instrument collection, search our catalogue on the Archives Hub.