Inside the archive: Restoring Joyce and Belli

-

Anna Edwards

- 9th March 2023

-

category

- Blog Posts

In the second of our blog posts about recent work to preserve the Foundation’s book collection, we focus on books relating to two of Burgess’s favourite writers: James Joyce and the Roman poet Giuseppe Gioachino Belli (1791-1823). (Read the previous post here.)

Following repair work carried out by the book restorers Formbys, these volumes are now available for consultation by researchers. We are grateful to everyone who has supported this work through their donations to the archive.

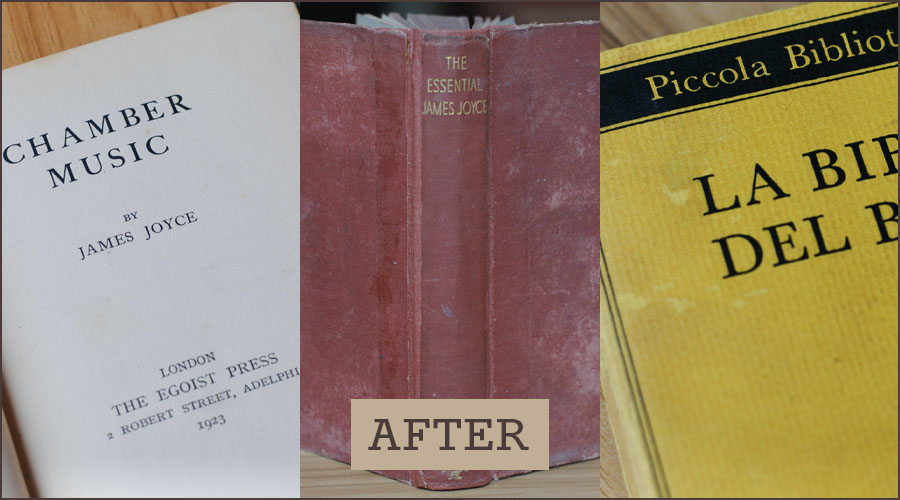

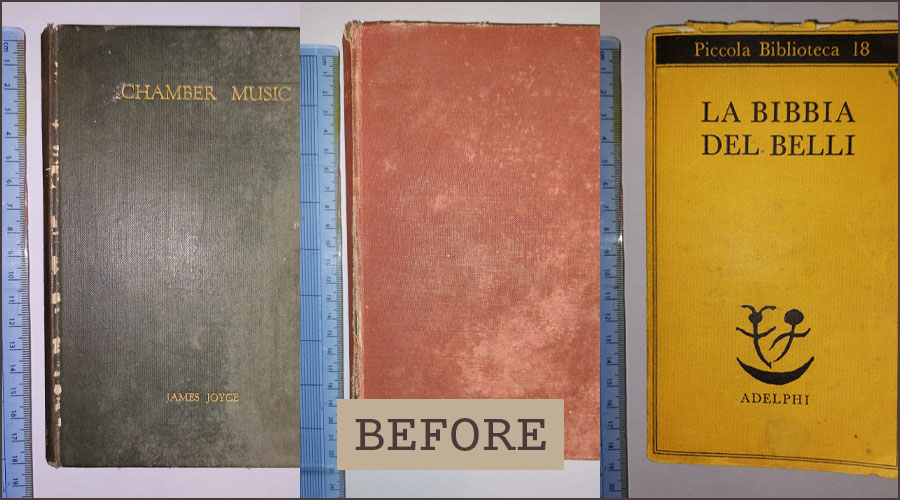

Chamber Music by James Joyce (Egoist Press, 1923)

Burgess’s love of James Joyce began while he was a student at Xaverian College in Manchester. In Little Wilson and Big God, he recalls that in 1934 ‘my history master smuggled the Odyssey Press edition [of Joyce’s Ulysses] out of Nazi Germany and lent it to me.’ It was a seminal moment in Burgess’s life. As he wrote later, ‘When we have read [Joyce] and absorbed even an iota of his substance, neither literature nor life can ever be quite the same again.’

Also in 1934, Burgess acquired the earliest surviving book by Joyce in our collection: a 1923 reprint of Chamber Music. This collection of 36 poems was first published in 1907. Burgess has inscribed the inside cover twice: ‘John Burgess Wilson / Manchester 1934’ and ‘To Lynne from John, 1939’. ‘Lynne’ refers to Burgess’s first wife, Llewela Jones, a fellow student at the University of Manchester, whom he married in 1942. Burgess and Lynne had a turbulent relationship, but this inscription is testament to the tenderness and affection that existed between them. Chamber Music is largely a collection of love poems, and it seems that Burgess gave this volume to Lynne during the first year of their courtship.

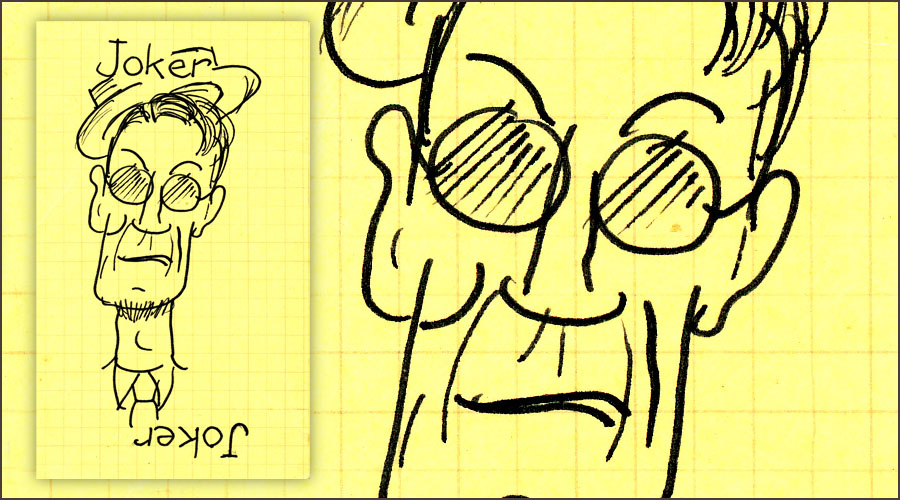

Burgess claimed to have made musical settings of poems from Chamber Music in his youth. The only surviving setting is ‘Strings’, the first poem in the collection. He also set one of Joyce’s later poems, ‘Ecce Puer’, written for the birth of his grandson. Other work inspired by Joyce includes Blooms of Dublin, a musical based on Ulysses, reams of journalism, two critical studies, and even a pack of hand-drawn playing cards.

The Essential James Joyce, edited by Harry Levin (Jonathan Cape, 1948) and La Bibbia del Belli, edited by Pietro Gibellini (Adelphi, 1974)

Burgess read Joyce voraciously. The Foundation’s book collection contains around 60 works by or about Joyce in English, Italian and French — including novels, biographies, editions of letters, collections of images, a cookery book, and commentaries his work. One of these books — The Essential James Joyce, edited by Harry Levin — was, like Chamber Music, a much-valued possession, carefully kept over many years and through multiple house-moves.

The book was acquired by Burgess while he was teaching at Bamber Bridge Emergency Training College, near Preston. It is stamped ‘Bamber Bridge Training College Library’ and inscribed by both Burgess and Lynne. A later bookplate has been added — this time by Burgess and his second wife, Liana — identifying the book as part of their private library.

The book’s importance stems not only from what it says about Burgess’s interest in Joyce, but also because it tells us about one of Burgess’s other passions: the poetry of Giuseppe Gioachino Belli. Just as his discovery of Joyce was a seminal moment in his youth, so Belli was, as he said in You’ve Had Your Time, ‘one of the three major revelations of my later life.’

An unpublished poet in his lifetime, Belli wrote more than 2000 sonnets, known as the Sonetti Romaneschi, which are striking both for their volume and content. Written in the local Roman dialect, rather than standard Italian, the sonnets are composed from the viewpoint of the poor and frequently satirize the clerical world that oppressed them.

Burgess was impressed by Belli, whose poetry inspired several creative projects. Most ambitiously, Burgess planned to translate all of Belli’s sonnets into his own ‘Lancashire English’. His copies of Levin’s Essential James Joyce and Pietro Gibellini’s La Bibbia del Belli help to document this project.

Burgess began translating Belli in the mid-1970s, collaborating with Liana and the linguist Susan Roberts, a speaker of Roman dialect who stayed in the Burgess house in 1975 and 1976. Roberts produced literal translations of the sonnets, which she passed to Burgess to rework into verse. The well-thumbed and annotated copy of Gibellini’s edition, La Bibbia del Belli, was the main source-text for the translations later published in ABBA ABBA.

Many of Burgess’s handwritten draft translations can be found in a diary from 1974, and there are scatterings elsewhere. For example, the endpapers of The Essential James Joyce contain an early draft translation of ‘The Annunciation’ by Belli.

Burgess initially proposed to publish a self-standing book of his Belli translations, but these were eventually incorporated into the novel ABBA ABBA, in which the dying poet John Keats meets Belli in Rome. The poetry of Belli, and his memorial statue in Trastevere, are both referred to in the novel Beard’s Roman Women. Ronald Beard, the novel’s protagonist, shares a few attributes with Burgess, including an apartment close to the Piazza G.G. Belli in Rome and a desire to translate Belli’s sonnets, assisted by his partner Paola Belli, who is directly descended from the poet.