Inside the archive: the poetry of Anthony Burgess

-

Anna Edwards

- 19th February 2021

-

category

- Blog Posts

In our latest article for the Inside The Archive blog series, we consider the extensive collection of poems by Anthony Burgess in the Manchester archive.

Anthony Burgess never lost his early passion for poetry and continued to experiment and engage with this literary form throughout his career.

In the new edition of Burgess’s Collected Poems published by Carcanet, Jonathan Mann presents Burgess’s poetry in full detail, bringing together around 350 poems and verses, of which a fifth are previously unpublished.

The Burgess Foundation’s collection played a key role in assembling the volume, and this blog provides information about how people who want to engage with Burgess’s poetry can explore the wealth of available material within our library and archive, beginning with the online catalogue on the Archives Hub.

Burgess produced hundreds of poems over the course of nearly 60 years, including everything from epic poems to occasional verses and lyrics, so it’s not surprising that poetry can be found throughout many parts of the archive. Poems created by Burgess as part of his work on literary and dramatic projects have been described, for cataloguing purposes, alongside other material relating to that work.

For example, drafts of his verse novel Byrne (1995) are described alongside his preliminary plans for the book, and drafts of Moses: A Narrative (1976) can be found alongside Burgess’s foreword and further material relating to the television mini-series, Moses the Lawgiver (1974).

Beyond such examples of Burgess’s long-form poetry, several of his prose novels contain original poems, particularly the Enderby series, which has as its heart a fictional poet named F.X. Enderby. Researchers can explore these poems in detail among drafts of several Enderby novels within the archive.

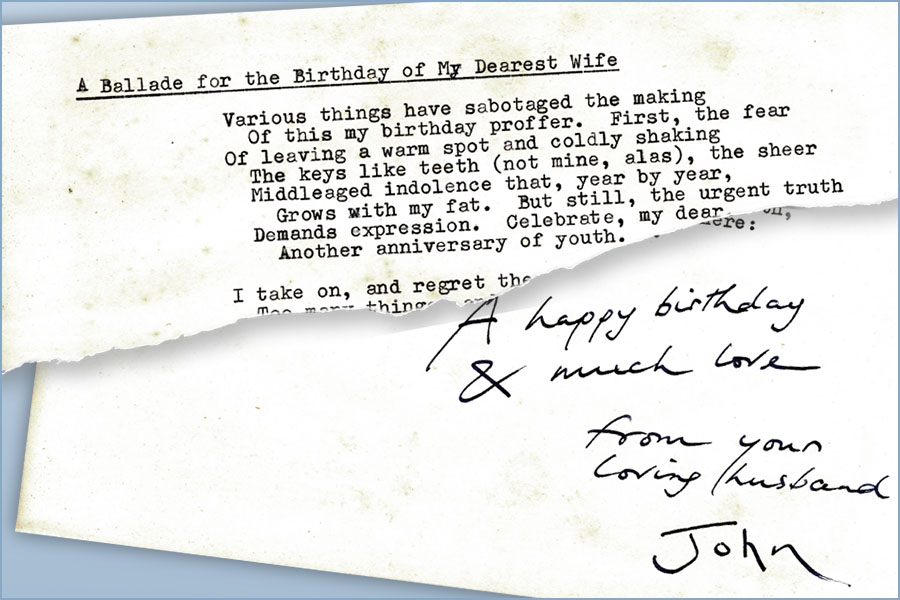

Occasional poems and lyrics by Burgess, which do not form part of his work on an identifiable project, have been catalogued as a distinct series of records. Where possible, poems have been catalogued according to the title given by Burgess but, where a poem is untitled, the first line is given in quotation marks. Most of the poems in this group date from the 1970s, but there are important examples dating from the 1950s, when Burgess was teaching at Banbury Grammar School in Oxfordshire and, subsequently, at Malay College in Kuala Kangsar, Malaysia. The content of the series is diverse, encompassing poems written in English and, occasionally, in Italian or French; poems written with a view to publication, such as ‘In Memoriam Wystan Hugh Auden’ and ‘To Vladimir Nabokov on his 70th Birthday’; and those which were intensely private, such as poetry for his wives, Lynne and Liana (see Ballade, pictured top). Considered pieces such as verse inspired by James Joyce’s Ulysses sit alongside others apparently written off the cuff, such as an untitled poem beginning ‘Tout passe / L’art robuste’, scribbled on a business card from a Chinese restaurant.

Further poems by Burgess have survived in his uncatalogued correspondence, such as a verse letter addressed to Emery Collegiate Institute in Canada in which he dismisses A Clockwork Orange (1962) as ‘a foul farrago’.

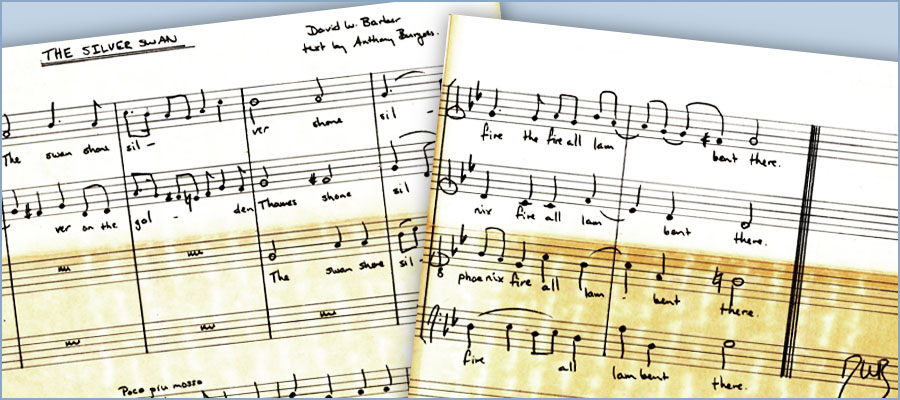

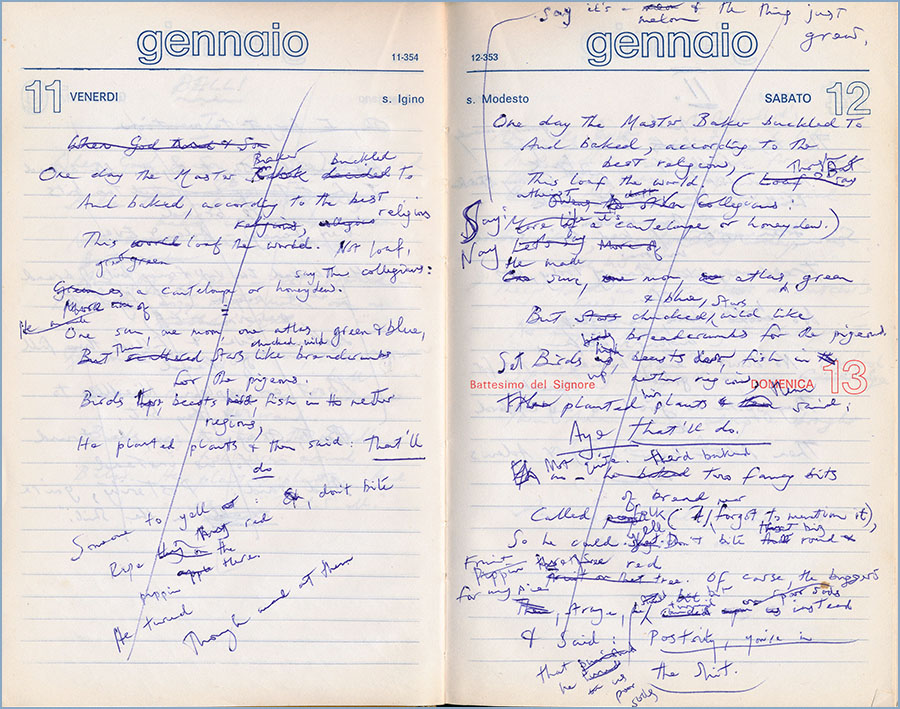

Others exist on the fly-leaves of books in Burgess’s library; jotted in notebooks and diaries; or, indeed, as music. For example, Burgess’s poem ‘The Silver Swan’, possibly inspired by a madrigal by Orlando Gibbons (1583-1625), survives in the collection as part of a composition by David W. Barber.

Barber’s setting of Burgess’s poem was found within a copy of Jeffrey Holme’s Shakespeare was a Computer Programmer (Brunswick Press, 1975) in Burgess’s library, apparently a gift from Barber. The score is inscribed ‘for Mr Anthony Burgess, with respect and gratitude,’ and forms part of a correspondence between the two men. In 1985 Burgess wrote the preface to a book by Barber, Bach, Beethoven and the Boys: Music History As It Ought To Be Taught, and Barber subsequently sent Burgess a signed copy of his book When the Fat Lady Sings: Opera History As It Ought To Be Taught (Toronto: Sound and Vision, 1990).

Although most of Burgess’s poems survive as literary manuscripts, some exist only as audio recordings. During the 1970s, for example, while he was translating a selection of sonnets by Giuseppe Gioachino Belli (1791-1863) with the help of Susan Roberts, he recorded himself reading from his draft translations as part of the editorial process. This audio recording of Burgess reading ‘The Creation of the World’ differs from both his handwritten drafts and the published text:

Beyond exploring original and adapted poetry by Burgess, researchers may be interested to discover more about the poetry and poets that he read and admired. Burgess’s journalism, published volumes of literary history, and his wide-ranging collection of poetry books provide a series of contexts for his original poetic work.

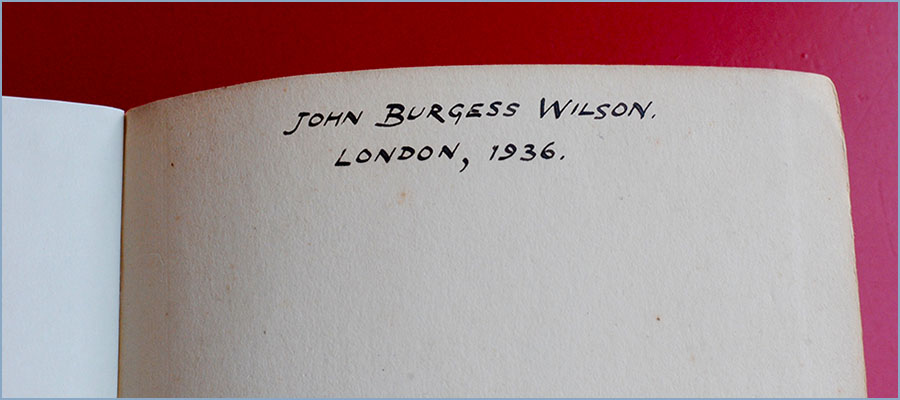

Books inscribed by Burgess during the 1930s, which now survive at the Burgess Foundation, document his early interest in the poetry of John Donne, T. S. Eliot (see Collected Poems inscription below), James Joyce, Ezra Pound, and William Shakespeare, and sit alongside volumes of poetry from the late-medieval period to the twentieth century. Burgess’s vinyl collection includes readings of works by Boris Pasternak and Ernest Hemingway, and his own musical compositions include settings of D.H. Lawrence, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Thomas Nashe, Gabriele D’Annunzio, Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe, Ben Jonson, Charles D’Orleans, Walter Savage Landor, and Ezra Pound.

If you have any questions about the collection or how to access it, please contact the Archivist on anna@anthonyburgess.org