Is Shakespeare Relevant?

-

Anthony Burgess

- 29th June 2024

-

category

- Blog Posts

Anthony Burgess wrote this essay for the New York Times in 1970, the year in which his Shakespeare biography was published. After completing a lecture tour of Europe and the United States, he was teaching at Princeton University.

I’ve spent the last couple of years, off and on, in two worlds simultaneously — imaginatively in Elizabethan England, corporeally in America. On one level the worlds are closer than you’d think: New York, for instance, has all the scatology, garbage and violence of that old London, complete with blood on the sidewalks.

My particular concerns have been, on the one hand, Shakespeare and, on the other, American campuses from Seattle to Chapel Hill, from Los Angeles to Princeton. Inevitably I’ve been interested to see how much or little the now generation finds of relevance (to use a now term) in a very-much-then poet.

In the first place, students enter English departments knowing practically nothing about Shakespeare: something is wrong, evidently, in the high schools. They’re vaguely aware of an ancient Englishman who wrote plays in ancient English, and they’re vaguely wrong on both counts. Shakespeare died four years before the landing on Plymouth Rock, and that makes him a pillar of American culture. His language, especially in its pronunciation (as I’ve tried to demonstrate all over the Union), is far closer to Nixonian or Black Panther English than to the dialect of Elizabeth II.

Describe Shakespeare’s probable person, or show pictures of it, and the students start to sense a somatic and sartorial kinship. He had long hair and beard, wore earrings, and showed the shape of his legs and his bottom. Nothing uptight there, nothing of Emerson, Longfellow or General Motors. He probably washed very little and never took a bath, which makes him modish. He lived under a repressive government, with state police, wasteful (if necessary) military expeditions, rebels in jail, swordplay on the streets, gross mugging. He knew (and this appeals greatly) small Latin and less Greek.

But how about the plays? Most students come to college knowing at least the plots of Romeo and Juliet and Hamlet. These favourably dispose them toward Shakespeare, since he seems to be on the side of kids rebelling against the establishment. Romeo and Juliet is not unlike West Side Story, which many students have seen as an Old Movie.

Hamlet is a mature student himself, at least a sophomore, and his wicked stepfather makes the mistake of not letting him go back to the campus, so that the black-jumpsuited prince conducts riots at home and finally topples a corrupt government. The monologues, especially as done in the sub-standard English of Nicol Williamson, are very much now-generation stuff, what with their worry about something being rotten in the state and their romantic impotence in the face of the big political machine. Hamlet’s feigned madness is, when you come to think of it, a sort of self-indulgent trip.

But all the plots of Shakespeare are, as the kids discover, pregnant with present relevance. Black is beautiful (Othello, Cleopatra), also powerful, but Mister Charlie does for them. Women out-talk men (Beatrice), succeed in the professions (Portia, Joan of Arc), plot murder (Lady Macbeth). Useless wars kill men and destroy civilizations (the history plays); dictators come to sticky ends (the Roman plays). Wealth is a snare (Timon of Athens), virginity a joke (Measure for Measure), colonialism intolerable (Caliban — Shakespeare’s one American character — in The Tempest).

The plots are fine, but these alone may, if they hear of the book, lead the students to Lamb’s Tales from Shakespeare. They need the poetry, but they regard the poetry as wordy, flowery, Spironian; its vocabulary has somewhat over a hundred items. But I think, however, they can be reconciled to it if they take it as the Elizabethan equivalent of a drug experience — euphoria and flashing lights. A man, after all, is entitled to do his thing, and Shakespeare, by God, was doing it.

I once made a big mistake when lecturing on Shakespeare to some American postgraduate students in Deià, Mallorca. Oppressed by a hippysim which seemed, in its elected rags, to mock the peasants in their enforced rags, I put on a collar and tie (the first ever seen in Deià) and spoke on Shakespeare, the ambitious, the money-getter, the ultimate bourgeois.

The students were appalled to hear of a poet acquiring a big house equipped with one of the new Harrington water-closets (and who can doubt that Shakespeare today would have a colour TV and dishwasher?). Shakespeare, they took it, sold out instead of dropping out. They went off to play their transistors, or drink ice-cold 7-Up, or tear down the Mallorcan roads in their jalopies, or burn their Shakespeares with their Zippos. Just another materialist, they said, another writer corrupted by consumption, wanting the best of both worlds. We, they implied, are, thank God, not like Shakespeare.

Our online exhibition about Burgess and Shakespeare is here.

Buy the book: Shakespeare by Anthony Burgess (affiliate link)

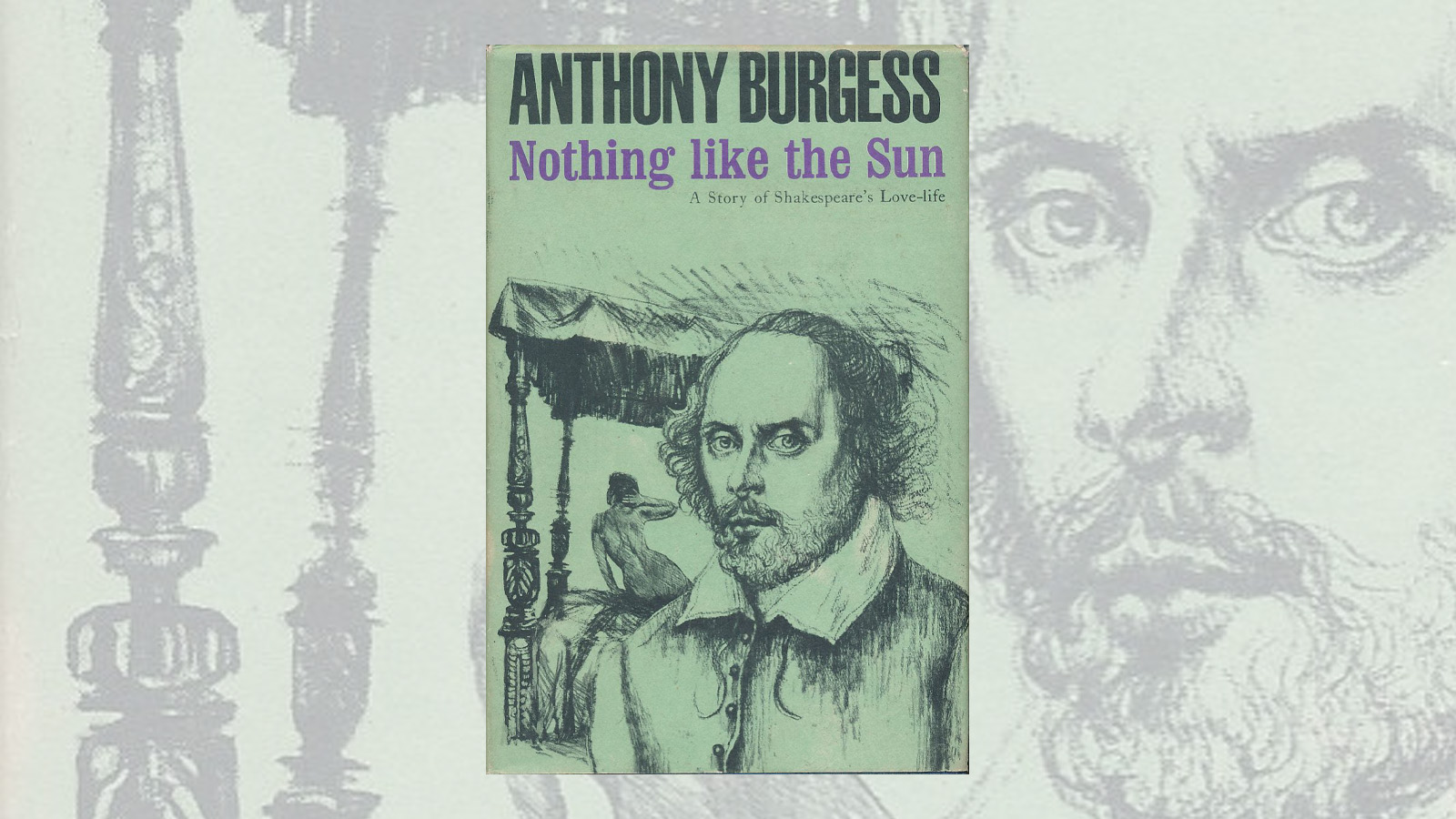

A new edition of Nothing Like the Sun, a novel written in Elizabethan English, will be published by Galileo Books in October 2024.