Lynne Burgess at 100

-

Andrew Biswell

- 24th November 2020

-

category

- Blog Posts

-

tagged as

- A Clockwork Orange

- Adderbury

- Archive

- Banbury

- Beard's Roman Women

- Charles Dickens

- Christopher Isherwood

- Gollancz

- Gore Vidal

- Inside The Archive

- JB Priestley

- Jean Pelegri

- Kingsley Amis

- Little Wilson and Big God

- Llewela Jones

- Llewela Wilson

- Lynne Burgess

- Lynne Wilson

- Manchester University

- Michel de Saint Pierre

- Michel Servin

- Second World War

- Sidgwick & Jackson

- The Irwell Edition of the Works of Anthony Burgess

- The Malayan Trilogy

- The Man Who Robbed Poor-Boxes

- The New Aristocrats

- The Olive-Trees of Justice

- The Right To An Answer

- The Wanting Seed

- Translation

- W.H. Auden

- You've Had Your Time

Looking back on the life and work of Llewela Jones (1920-1968).

Anthony Burgess’s first wife, born Llewela Jones and later known as Lynne, would have celebrated her 100th birthday on 24 November 2020. Many readers are familiar with the portrait of her given by Burgess in his two volumes of autobiography, Little Wilson and Big God (1987) and You’ve Had Your Time (1990). It is worth noting that he was married to another woman when he wrote these books, and during the period of his second marriage he sometimes played down the significance of Lynne. She was not only his companion, but also his literary collaborator: they translated three novels together in the 1960s, with Lynne undertaking most of this work. In the years since she died in 1968, at the age of 47, the narratives about her death have often overshadowed a life that was full of energy and creativity.

Llewela Jones was born in Bedwellty, Monmouthshire, and attended the grammar school there, of which her father was the headmaster. A graduate of Manchester University, where she studied Modern Languages and Economics, Lynne married Burgess in January 1942. During the Second World War she lived in London and worked for the government on secret plans for the D-Day invasion of Normandy in 1944. She befriended Sonia Orwell and soon became a presence on the London literary scene, frequenting writers’ pubs such as the Fitzroy Tavern and the Wheatsheaf. In the early 1940s she had an affair with Dylan Thomas. She remained friendly with him and later introduced Burgess to him: he recalled an early-morning meeting at the bar at Richmond station, where Thomas lined his stomach with lime juice to help him endure the day’s drinking which lay ahead.

In the 1950s, Burgess and Lynne lived for four years in Adderbury, Oxfordshire, where she taught classes for the Workers’ Educational Association. He looked back on this as the happiest time in their life together. Burgess and Lynne were regulars at the Red Lion in Adderbury, and they sometimes ran the bar when the landlord was away. In 1954 they moved to Kuala Kangsar in Malaya, where Lynne filled their house with exotic pets, including a civet cat, a turtle and a snake.

Returning to England in 1957, Burgess and Lynne lived for several months at her father’s house on Franklyn Road in Leicester. Visiting a nearby pub called the Black Horse, she overheard a scandalous story about wife-swapping, which later became the plot of Burgess’s novel, The Right to an Answer.

The first of Lynne’s published books is the English translation of The Olive-Trees of Justice by Jean Pélégri, published by Sidgwick and Jackson in 1962. The title page credits ‘Anthony Burgess and Lynne Wilson’ as translators. This novel about the Algerian uprising against French colonial rule was awarded the Grand Prix Catholique de Littérature. The background of terrorism, malaria, alcoholism and tobacco-addiction broadly resembles the atmosphere of Burgess’s Malayan Trilogy. Reviewing the English version in the Times Literary Supplement on 6 July 1962, Walter Keir wrote: ‘Brilliantly done, and all the better for being so restrained, this novel has a sad and passionate sincerity about it which cannot fail to be deeply moving.’

Her next book is in many ways her most distinguished literary production. The New Aristocrats by Michel de Saint Pierre, translated from the French by ‘Anthony and Llewela Burgess’, was published by Gollancz in 1962, with an American edition published by Houghton Mifflin in 1963. This novel about delinquent teenagers at an elite French boarding school has many connections with A Clockwork Orange, which appeared in the same year. The novel’s hero, Denis, is an intellectual rebel who is inclined towards wickedness and criminality. He displays his evil credentials by riding a motor-scooter named Satan.

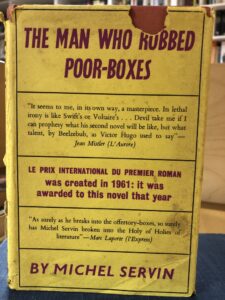

The third of Lynne’s collaborative translations is The Man Who Robbed Poor-Boxes (original French title: Deo Gratias) by Michel Servin, published by Gollancz in 1965. The novel is an ironic confession by a thief, broadly in the style of Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground. Reviewing this book, which won the inaugural Prix du Premier Roman in France, the critic Jean Mistler wrote: ‘It seems to me in its own way a masterpiece. Its lethal irony is like Swift’s or Voltaire’s.’ No translator is named on the title page, because there had been a dispute with the publisher. Documents in the publishing file suggest that the translation by Burgess and Lynne was given a polish before the book appeared.

In a letter to a friend, written in the early 1950s, Burgess reported that Lynne was working on a novel set in a girls’ school, and that she was typing up her manuscript. What became of this novel remains a mystery — the typescript is not present in any of the Burgess archives — but it is very likely that further evidence of Lynne’s literary work will come to light in the future.

Another unpublished work by Burgess and Lynne is worth recording here. This is a history of London, written to commission in 1962 but never published, apparently because it was thought to be insufficiently factual and (Burgess claimed) ‘too literary’. The manuscript includes a note which states that most of the research on this book was undertaken by Lynne, who worked in collaboration with Diana and Meir Gillon, to whom The Wanting Seed is dedicated.

Many other traces of Lynne are present in the Burgess Foundation’s archive. In particular, a number of joint diaries kept by Burgess and Lynne have survived in the form of manuscript notebooks, and these are currently being transcribed by a team of researchers. It is clear that Lynne made substantial contributions to these private journals, which contain (for example) a set of insulting limericks that she wrote about Burgess. Some of these informal poems are described in a blog post here.

Lynne often appears, adding sentences or paragraphs, in exchanges of letters between Burgess and his publishers. She was an active presence on the London literary scene in the 1960s, often attending parties with Burgess. Some of these occasions have been recollected in print by writers such as Gore Vidal (in his essay collection, United States) and Kingsley Amis (in his Memoirs). Her home life is described in a poem by Martin Bell, who was a friend and neighbour in Chiswick after the Burgesses moved there in 1964. One of Bell’s poems, dedicated to Lynne, celebrates her menagerie of cats and dogs. The poem appears in the 1967 volume of his Collected Poems.

Another valuable source of information about Lynne is the extensive collection of her books, now held at the University of Angers and at the Burgess Foundation in Manchester. Taken together, the catalogues of these book collections reveal a great deal about Lynne as a reader, both before and after she met Burgess.

Annotated volumes in the Foundation’s book collection suggest that Lynne had a reading knowledge of several languages, including French and Spanish. Her copy of Les Fleurs du Mal by Charles Baudelaire dates from 1941, when she was still a student. A hardback copy of The Ascent of F6 by W.H. Auden and Christopher Isherwood seems to have been an early gift from Burgess. This book is dated 1938, the year of their first meeting in Manchester. Elsewhere we find several works of history, such as a 1942 edition of Religion and the Rise of Capitalism by R.H. Tawney.

Inscribed copies of The Pickwick Papers and A Christmas Carol indicate that Dickens was one of Lynne’s favourite authors. Her treasured hardback editions of Jane Austen have been read so heavily that they are almost falling to pieces. Other books from her collection include Angel Pavement by J.B. Priestley, The Heart of the Matter by Graham Greene, The Good Soldier by Ford Madox Ford, and Decline and Fall by Evelyn Waugh. A copy of T.S. Eliot’s edition of Rudyard Kipling’s poetry contains Lynne’s ownership marks and a stamp indicating that the book was formerly the property of Bamber Bridge Training College Library. Rather unexpectedly, there is also a copy of Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, inscribed to Lynne as a birthday gift from Burgess.

Further research into Lynne’s notebooks and library will allow researchers to discover more about her. Her memory is also celebrated in Beard’s Roman Women, Burgess’s ghost story about a man whose deceased Welsh wife continues to haunt him through a series of spectral telephone calls. This novel has appeared — with colour photographs by David Robinson — in the Irwell Edition of the Works of Anthony Burgess, edited by Graham Foster and published by Manchester University Press.