Martin Amis on Anthony Burgess

-

Andrew Biswell

- 30th August 2023

-

category

- Blog Posts

-

tagged as

- 1984

- 1985

- A Clockwork Orange

- ABBA ABBA

- Belli

- Burgess at 70

- Drinking

- dystopia

- Earthly Powers

- Enderby

- Evelyn Waugh

- Feminism

- George Orwell

- Graham Greene

- Kevin Jackson

- Liana Burgess

- Little Wilson and Big God

- Martin Amis

- Monaco

- New Statesman

- New York Times

- Nineteen Eighty-Four

- Observer

- Paolo Andrea

- Russell Davies

- Visiting Mrs Nabokov

Martin Amis, who died in May 2023 at the age of 73, was one of the most widely admired figures in Anglo-American literary fiction, bestriding the world of books like a colossus from the 1970s until the 2020s. He engaged widely with contemporary fiction through his work as a literary journalist and interviewer. It was in this capacity that he encountered several works by Anthony Burgess.

Martin Amis was one of the few people who met Burgess in the company of both of his wives. He first met Burgess and Lynne at a party organised in the 1960s by his father and stepmother. Amis recalled: ‘I have a faint image of a jovial, talkative man, consistently out-decibelled by his wife.’ His impressions of Liana were more favourable.

The close connection with Burgess began soon after Amis was hired as literary editor of the New Statesman in 1976. According to a letter in the archive, Amis wrote to Burgess with an invitation to review a batch of new books about feminism. Sadly, there is no evidence of this review having been written or published. It is unclear why Burgess was thought to be an expert on feminism — perhaps he was expected to deliver a piece of knocking copy? — but he was later asked to review A Feminist Dictionary for the Observer.

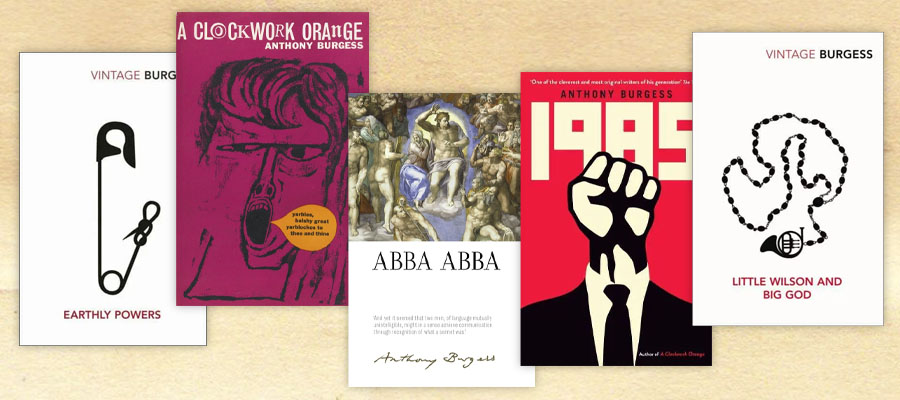

In the late 1970s, Amis wrote articles about ABBA ABBA and 1985, for the New Statesman and the New York Times. While he was reasonably affirmative about the Keats section of ABBA ABBA, which is said to be a work of ‘hectic orchestration,’ he expressed some reservations about the translations of Belli’s obscene Roman sonnets into Lancashire English in the second half of the book.

He showed his teeth when passing judgement on 1985, emptying a large bucket of scorn on Burgess for his apparent misreadings of George Orwell in the non-fiction section of the book. Amis claimed that the novella ‘1985’ merely presents ‘a stoked-up 1976’, and he said that the book as whole was a failure of imagination on the part of Burgess the novelist. Voicing the opinion that 1985 was, creatively and linguistically, inferior to A Clockwork Orange, Amis concluded that ‘Burgess’s 1985 is too chaotic to be a metaphor for anything but chaos.’ The only consolation was that the book made him want to re-read Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Amis met Burgess in the company of Liana and Paolo Andrea when he travelled to Monaco for an interview commissioned by the Observer in 1980. The resulting profile was later reprinted in a collection of essays titled Visiting Mrs Nabokov and Other Excursions. This was the occasion of the famous lunch, which Amis described as follows:

We started off with big gin and tonics in his local bistro, then a very great deal of wine, and then, at about five o’clock, he was drinking triple brandies with one swallow. And then, as I was staggering out, he was ordering gin and tonics. It was all going to start again, for him. I swear that lunch took me four or five days to recover from. But I’m sure he went back, wrote a symphony, finished a novel, and then did the housework.

When Amis reviewed Earthly Powers for the New York Times in 1980, he welcomed the book as a triumphant return to form. ‘Even at 600 pages,’ he wrote, ‘the book feels crowded, bursting with manic erudition, garlicky puns, omnilingual jokes.’ Burgess was said to be a more brutal chronicler of good and evil than other Catholic writers, such as Graham Greene and Evelyn Waugh. The moments of affirmation were mostly to be found in the area of artistic creation, with Toomey’s impressive collection of (fictional) plays, novels, operas and Broadway musicals. The figure of the protagonist as artist is what redeemed the novel for Amis, and prevented it from being a bleak or hopeless vision of the twentieth century. Earthly Powers, he concluded, ‘is a considerable achievement, spacious and intricate in design, wonderfully sustained in its execution, and full of a weary generosity for the errant world it recreates.’

Amis was equally warm in his appreciation of Little Wilson and Big God, which he reviewed for the Observer in 1987. He commented on the extravagance of the provincial life described by Burgess in this first volume of his autobiographical confessions: ‘Twenties Manchester, as evoked in these early pages, is even more exotic than Fifties Malaya and Brunei. […] This is the world of Mrs Winslow’s Soothing Syrup, and tobacco called “Baby’s Bottom (smooth as a)”, the world of five-course breakfasts, tenpenny bottles of Medoc, forty-year courtships.’ Amis ended his review by expressing admiration for ‘Anthony Burgess’, perhaps the most impressive fictional character invented by John Wilson. The man who emerges from Little Wilson and Big God, he writes, ‘is a composite glued together by energy. He has built many mansions with this peculiar house of cards.’

Amis was one of the contributors to Russell Davies and Kevin Jackson’s television documentary Burgess at 70, first broadcast on BBC2 in February 1987. Commenting on the qualities of Burgess’s fiction, Amis said: ‘What I value most in him is that he’s beyond the parish pump. He is truly international. He doesn’t write novels about divorces and alimonies and domestic unhappinesses, which are usually the subject of English fiction. As an undergraduate I thought of him as someone who used language vitally and vigorously and was also undiscriminating in his areas of interest. He would follow his poet Enderby into the bathroom and stay with him. He did not close doors on his characters. He stayed with them all the way.’

Amis’s final statement about Burgess’s work was his foreword to the ‘Restored Edition’ of A Clockwork Orange in 2012. His approval of Burgess as a literary technician emerges clearly from a detailed summary of how the book works. In particular, Amis is keen to interpret the novel as a moral statement, bolstered by its inventive approach to building a new narrative language. Although this foreword did not appear in the US edition of the book, it was reprinted in the New York Times and in The Rub of Time, a collection of Amis’s essays.

Summing up Burgess’s achievement in 1987, Amis said: ‘Perhaps we’ll need a few years before we can settle down and have a look at his corpus. Nowadays we’re just so stunned by this foundry, this Vesuvius over in Monte Carlo. Every couple of weeks there’s something else from him. I haven’t got time to keep up with him. If I did nothing else, I might be able to.’

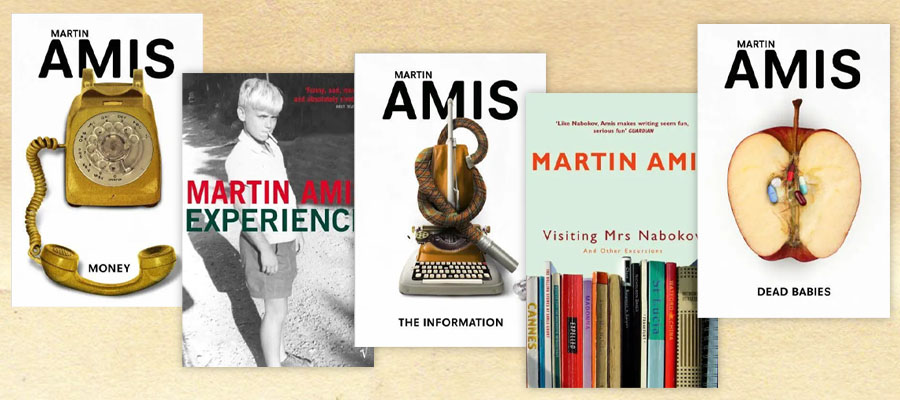

Looking back on Amis’s own literary career, it is clear that — like Burgess in the generation before him — he was, beyond his work as a novelist, also a gifted critic, memoirist and cultural commentator. His enduring fame is likely to depend on one particular novel — in this case, Money: A Suicide Note. It’s important to add that much of Amis’s best writing is to be found in works that are often overlooked by commentators, such as Dead Babies, The Information, Visiting Mrs Nabokov, Experience and The War Against Cliché.

Like all true writers of talent, his impressive legacy of novels and non-fiction books defies easy categorisation. Amis had many imitators in his lifetime but no equals. Now that he has gone, we must hope that his work will continue to be discovered by new generations of readers. It deserves nothing less.

Further reading: essays on Burgess by Martin Amis.

‘Anthony Burgess’ in Visiting Mrs Nabokov and Other Excursions (1993).

Reviews of ABBA ABBA, 1985, Earthly Powers and Little Wilson and Big God reprinted in The War Against Cliché (2001).

‘The Shock of the New: A Clockwork Orange Turns 50’ in The Rub of Time (2017).