Military Burgess: The British Way and Purpose

-

Graham Foster

- 14th February 2013

-

category

- Blog Posts

In October 1940, John Burgess Wilson was merely another reluctant conscript whose army number was 7388026. At this point, his ambitions lay in the musical, rather than the literary, and he even converted his military identification into a ‘catchy little tune’ as a mnemonic.

The first years of Burgess’s war were taken up with several temporary home-based postings in the Royal Army Medical Corp (Northumberland, Cheshire), until he was posted to the Entertainments Section of the 54th Division of the RAMC. His job was to play the piano in the mobile unit, but he also fulfilled some of his musical ambition by composing and arranging songs for performance. At the end of 1943, his skills were needed elsewhere.

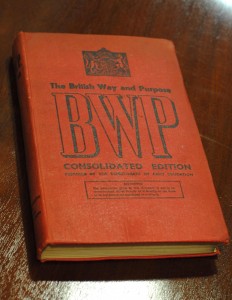

Burgess’s posting to Gibraltar was a safe one, far from the misery of fired guns and wounded comrades but it compounded his disgust of Army life. As part of the Education Corps, it was his job to enlighten his soldier-students in The British Way and Purpose (BWP), an anthology of essays on subjects ranging from the political justifications of the British Empire, to the prospective post-War establishment of a welfare state and the correct punishment of war criminals. These essays formed the foundation of a series of lectures Burgess had to deliver to the squaddies throughout his time in Gibraltar. The essays were written by numerous academics and blended statistics, history and light political theory with outbursts of optimistic propaganda, presumably to fire the soldiers’ blood after a dry lecture. For example, a particularly detailed and rather dull survey of the Commonwealth by one Vincent Harlow, ends: ‘In the hour of great adversity it [the Commonwealth] stood like a rock – alone against triumphant enemies; and by standing in that supreme crisis it made the gathering of the United Nations possible’. Many of the essays have contradictory elements, with Harlow, for example, stating that ‘Britain continued illogically to extend and develop this embarrassing Empire’ and an entire chapter by H.A. Marquand justifying the existence of the Empire by equating it to ‘being a member of a great, powerful, world-wide family instead of a citizen of a small, weak country’. Despite these contradictions, the overall message of the tome is that in order to stop the forces of totalitarianism and injustice, one has to be a ‘Responsible Citizen’: ‘If we shirk our responsibilities, if we hand over the management of our affairs to other people, if we think that six times a week to the cinema is better than doing a job for our neighbourhood and for our country then we are inviting dictatorship’.

It is easy to guess what Burgess made of the material he was being forced to teach. In his unhealthy military state (Andrew Biswell reports that Burgess was ‘dyspeptic, bitten by bed-bugs, tormented by migraines, and regularly smoking eighty cigarettes a day’), he may have smiled at chapter titles such as ‘The Army Selects the Fittest and The Army Makes Them Fitter’, or even rolled his eyes at some of the more purple passages about Britain’s glory against bullying foes. In the introduction to his dystopian novella 1985, he remembers that the BWP was ‘divided, even schizophrenic’ and that ‘Much of the material provided was embarrassingly diehard, with its glorification of a colonial system already in the process of being dismantled’.

Despite his misgivings, the BWP seems to have been a formative text for much of his subsequent writing. 1985 seems to be a direct response to some of its more socialist aspects with the hysterical condemning of the workers and their unions. Mr. Enderby, Burgess’s quintessential dirty poet, ruins a gala dinner by parroting the rhetoric of the BWP: ‘We look forward to a time when the world shall be free of the shadow of oppression, the iron heel and its swastika spur no longer grinding into the face of prone freedom’. In A Clockwork Orange, he is questioning the ability of the ‘responsible citizen’ to halt the advance of totalitarianism by showing pseudo-totalitarian forces attempt to brainwash Alex into becoming a responsible citizen. Much like Burgess’s time in Malaya, his period teaching The British Way and Purpose was influential in many ways, and seems to have helped him articulate his disgust of the rigours of Army life, even as far back as his first completed (Gibraltar-set) novel, A Vision of Battlements.

It seems rather fitting that Burgess spent VE Day in a prison cell, arrested by the Spanish Guardia Civil for drunkenly advertising the benefits of democracy in a bar. In his military life he claims he had ‘learned nothing except how to read company orders and do as little work as possible’. It is clear from his fiction that his military career, and The British Way and Purpose, taught him much more than this.