Music Review: The Bad-Tempered Electronic Keyboard by Anthony Burgess

-

Alex Crumbie

- 13th July 2018

-

category

- Blog Posts

In the final months of 1985, to mark the 300th anniversary of Bach’s birth, Burgess wrote the Bad-Tempered Electronic Keyboard, a modern tribute to Bach’s esteemed and influential Well-Tempered Clavier. Both compositions consist of 24 preludes and fugues, one for every major and minor key. Burgess stands in a long tradition of composing music in such a way, with Shostakovich having written his own 24 preludes and fugues in 1951, and Chopin, Scriabin and Debussy composing complete cycles.

The prelude, as its name suggests, started life as a piece of music that preceded a more substantial or complex piece, such as a fugue or a suite of dances. It emerged in the Renaissance period and was usually a short piece, largely improvised, which introduced the key or mode of the proceeding piece, and allowed the musicians to warm up their fingers and tune their instruments. Over time, and primarily due to Bach’s efforts, the prelude became a more refined and structured piece. Later composers abandoned the idea of the prelude as a precursor to another piece, cutting ties with the original concept and composing them as standalone pieces.

The word fugue comes from the Italian, fuga, meaning ‘flight’ or ‘to flee’, and is a reference to the lifeblood of the fugue: counterpoint, a compositional technique where melodies are woven in and out of one another, with the first melodic voice forever running away from those that follow. Although there are many variants of fugue, it usually has three main sections: the exposition, where the subject melody is introduced and is answered by the same melody appearing at a different pitch, usually up a 5th or down a 4th; development, where the subject and answer are explored in different keys; and the final section, where the subject returns in the tonic key, thus resolving the piece.

Burgess’s 24 Preludes and Fugues are a dialogue between the modern and the baroque: a clear example of neoclassicism. The form of the prelude and fugue immediately grounds the compositions in the past, a reference to Bach’s originals, but Burgess wastes no time in signaling to the listener that this set of compositions is going to be permeated with 20th Century tonality and harmony. The opening prelude begins with a pleasant melody, grounded in functional harmony, but quickly descends into dissonance, chromaticism and tonal ambiguity; the fugue follows in much the same way.

Scattered throughout the work are pieces that strongly evoke the baroque period, such as Prelude No. 4, which could quite easily have been written by one of Bach’s contemporaries. However, as the accompanying fugue develops, it descends into dissonance and chromaticism, pulling us back to the modern day, where harmony and tonality have been deformed and disfigured. Burgess’s ability to flit from one musical era to another, and back again, often within a single prelude or fugue, highlights his great compositional versatility and dexterity.

Although some of the compositions are manic and challenging, Burgess offers the listener some light relief by balancing these pieces with those that are delicate and gentle. Prelude No.10, although highly chromatic, is beautifully written. Tonally complex arpeggios fan out, like someone flicking through the pages of numerous books, sounding like something Debussy may have written after waking from a particularly odd dream. The chaos and dissonance of Fugue No. 2 creates a tension that is immediately resolved by the gentle chords of Prelude No. 3, a wonderful and calming piece. As this prelude progresses, it evokes the work of Satie, with its tranquility, subtlety and tonal richness, before finishing abruptly with a short, off-kilter melody.

Strange endings are found throughout The Bad-Tempered Electronic Keyboard. Many of the pieces, such as Preludes No. 3 and 11 sound as as if they have ended, not because they have exhausted the possibilities of a particular musical idea, but because Burgess wanted to move on to something else. Fugue No.17 is highly chromatic and tonally ambiguous, but the piece suddenly ends on a pleasant chord that feels incongruous with the rest of the piece. This resolution is like a musical deus ex machina, where the complex web of harmony is resolved in an instant, leaving the listener somewhat disappointed that all the narrative threads have not all been tied up.

The strangest ending is the piece that concludes Burgess’s set of preludes and fugues, FINALE: NATALE, a fugue based primarily on the hymn, Good King Wenceslas, the melody of which is hinted at in Fugue No. 24. The piece, written on the 13th of December, is simultaneously out of place with all the other pieces, but also very much in keeping with them, for the reason that Burgess’s Bad-Tempered Keyboard is, on the whole, rather bizarre. What makes these preludes and fugues challenging is also what makes them so intriguing and interesting. That Burgess chose to end his ode to Bach with a fugue based on Good King Wenceslas, whether you think it works or not, is characteristic of a composer who was jaunty, playful, mischievous, and always worth listening to.

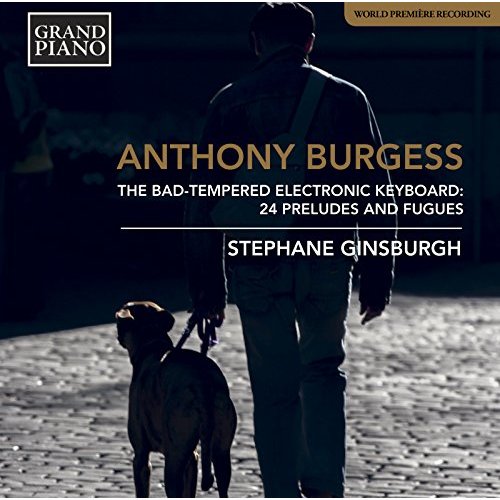

The Bad-Tempered Electronic Keyboard by Anthony Burgess, performed by Stephane Ginsburgh is out now on CD, download and streaming.