Review: A Clockwork Orange on stage in Paris, 2006

-

Yves Buelens

- 7th April 2021

-

category

- Blog Posts

-

tagged as

- A Clockwork Orange

- Beethoven

- Stanley Kubrick

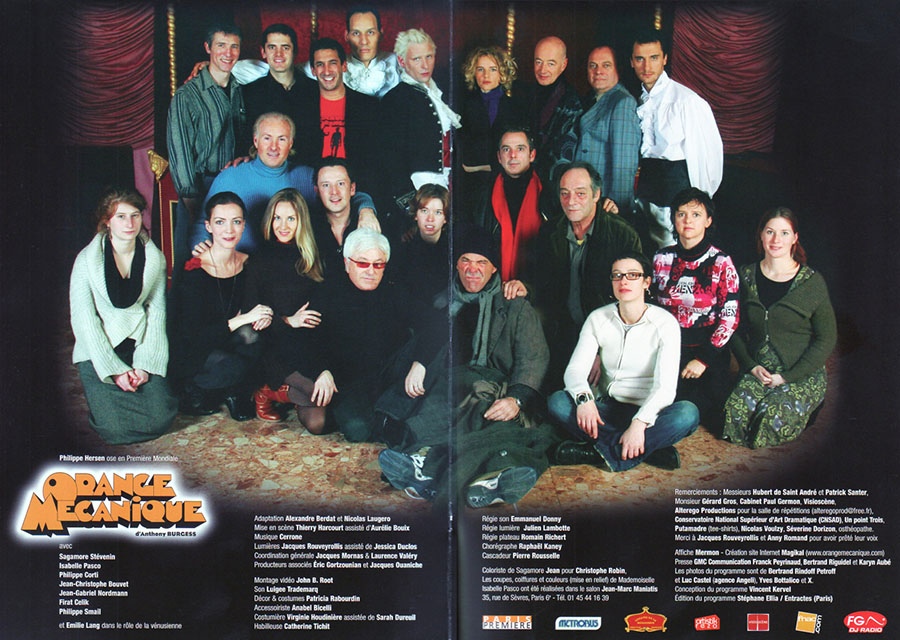

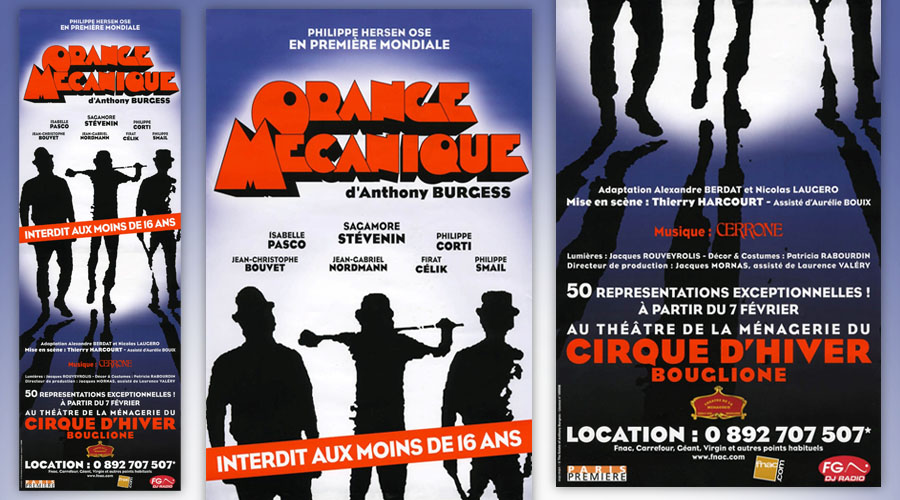

The first French stage production of A Clockwork Orange took place at the Théâtre de la Ménagerie at the Cirque d’Hiver in Paris in 2006. Yves Buelens, one of the Trustees of the International Anthony Burgess Foundation, was in the audience: here is his review.

The Théâtre de la Ménagerie stage production of A Clockwork Orange is not Burgess’s own stage version of his most famous novel but is an original adaptation of Kubrick’s movie on stage. It mixes elements of the novel with the iconic look of the movie.

The setting at the Cirque d’Hiver is special in itself: the theatre is rectangular in shape, and one half of the audience sits opposite the other, with seats occupying the long sides of the rectangle. There are two stages situated to the left and the right of the audience, and a mobile one built on rails in the middle. The decoration on this third stage is sparse: Mr Alexander’s desk, with an orange typewriter on top, a bookshelf and a chair. The action occupies one stage or another, and the mobile stage is used from time to time in the middle of the audience, or to double the size of the stages on either side.

When the show starts, Beethoven’s music rings out of the speakers. That is, Beethoven’s music re-arranged by the 1970s French disco star Cerrone. Two droogs, dressed more or less like those in the movie, are slouching on beanbags underneath a panel with the inscription ‘Korova Milkbar’ and a picture of Beethoven. The font used in the inscription is not precisely the one used in the movie. Then Alex walks on stage. He looks like a young Billy Idol with peroxide white hair, a black coat, a cane and a white shirt: the same Alex from the record shop in Kubrick’s movie. He is played by a young French actor, Sagamore Stevenin.

When the show starts, Beethoven’s music rings out of the speakers. That is, Beethoven’s music re-arranged by the 1970s French disco star Cerrone. Two droogs, dressed more or less like those in the movie, are slouching on beanbags underneath a panel with the inscription ‘Korova Milkbar’ and a picture of Beethoven. The font used in the inscription is not precisely the one used in the movie. Then Alex walks on stage. He looks like a young Billy Idol with peroxide white hair, a black coat, a cane and a white shirt: the same Alex from the record shop in Kubrick’s movie. He is played by a young French actor, Sagamore Stevenin.

The first couple of questions a Burgess aficionado asks at this point are: ‘Where is the third droog?’ and ‘Why did the writer change their names?’ Alex makes his opening speech to the audience. During the whole show he will address the audience, but he does not have Alex’s linguistic range from the novel and will therefore not mix old English words with Nadsat and contemporary words. Nadsat is not used much in the play, an omission which denies the audience access to one of the most important aspects of the novel, the actual brainwashing of the audience who, step by step, learn the language and, as a result, undergo the same experience as Alex. The words of the opening speech are Burgess’s from the book (‘We sat in the Korova Milkbar making up our rasoodocks …’). Alex and his droogs then mug a tramp in quite a graphic way. The production is restricted to people over sixteen, as announced on all the advertising posters, and can therefore be understood as a publicity stunt. The producer, Thierry Harcourt, continuously reminds the audience that it is the first time a play has been rated ‘R’ (over-16s only). Why it is so will become clear later in the production.

The next scene shows the attack on Mr and Mrs Alexander. The attackers still wear masks but without the phallic noses from the movie. The doorbell is still Beethoven’s Fifth. The violence of the assault is less intense than in the movie but the sexual assault is quite graphic (though with no full frontal nudity), as Alex rips Mrs Alexander’s T-shirt, exposing her breasts. He rapes her first on the desk, then gives her to his two droogs, who do the same with their trousers down.

Alex then goes home. We never see his parents. He delivers a speech (‘it was gorgeousness and gorgeosity made flesh’) while he blows up an inflatable doll with his foot, and disappears behind a curtain. We then see his shadow making love to the doll, no details spared (erection included). In the meantime an actor sits on the side of the stage and we recognize Mr Deltoid. When Alex has finished, he sits next to him and they talk. Mr Deltoid even has the same way of speaking as Aubrey Morris in the film, ending all his sentences with ‘yes’.

The two droogs are expecting Alex later in the afternoon, as in the film. Alex sets the record clear (‘No more picking on Dim, brother’) while the middle stage is transformed into the Cat Woman’s house. She is played by the same woman who played Mrs Alexander. All the actors play at least two roles, except Alex. The gigantic phallus is still on the desk but it is not used as in the movie. This time she is not killed by the phallus (bye-bye symbolism). When Alex goes inside the house she is not doing exercises, but modelling another impressive phallus in a dubious way. Alex is not knocked down by a bottle of milk but by pepper-spray. There goes another symbolic moment!

In the next scene, Alex finds himself in prison. It is a pity that the thematically very important speech by the chaplain is divided over two or three moments during the play. Alex then has to undress so that his clothes can be inventoried and put into a box. Alex strips completely: the first full-frontal nudity of the play. This is, in my opinion, unnecessary in the play but may help justifying the R-rating.

The brainwashing sequences use the ceiling of the theatre where pictures are screened: different ones than in the movie. Alex is strapped in a chair but the eye-opening props are not used. Before getting out of prison, Alex is tested: he gets beaten without reacting and then has a fully naked woman dance around him, rubbing her crotch on his face (R-rating justification).

The rest of the production respects the movie and the book but stops before Chapter 21. There is no mention of Alex growing old except in a line of dialogue where Alex confesses that he won’t be able to stop the actions of his son, just as his father was unable to stop his. The parents remain off-stage voices, which is a pity for Kubrickian blue wig aficionados.

The rest of the production respects the movie and the book but stops before Chapter 21. There is no mention of Alex growing old except in a line of dialogue where Alex confesses that he won’t be able to stop the actions of his son, just as his father was unable to stop his. The parents remain off-stage voices, which is a pity for Kubrickian blue wig aficionados.

What remains after the performance is the impression of having seen a brave attempt at transposing A Clockwork Orange onto the stage without using Burgess’s play. Unfortunately, in my opinion, the staging is based too closely on the iconic look of Stanley Kubrick’s movie. The play mixes literal elements from the novel with dialogue from the film version. It is like a movie sequel using only some elements of the first film that the audience is most likely to recognize. The poster even shows an image from the film.

Sagamore Stevenin does a good job portraying Alex, even if he has a tendency to ‘animalize’ Alex too much. He plays Alex without the arrogance seen in Kubrick’s movie (the transfer from prison to clinic sequence in the movie comes to mind). Stevenin plays it more like an animal, or a junky high on drugs, hardly walking straight, always bent over when in prison. One scene which is especially striking shows a prison warder walking Alex on a leash. In fact Stevenin was not cast as Alex until a few weeks before production began because the actor who was to play Alex, Sami Naceri (star of the French Taxi movie series), ended up in prison himself. The other actors offer an acceptable performance but there is no new Laurence Olivier to be seen.

That R-rating is justified but should not exist because the rated elements are not necessary to the play itself. It can be seen, therefore, more as a striking advertising ploy, playing on the public’s deep-seated belief that A Clockwork Orange is violent from beginning to end and contains little more than sexual elements.