Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Anthony Burgess

-

Andrew Biswell

- 25th February 2019

-

category

- Blog Posts

ONE: He received a fan letter from Umberto Eco.

They met when Burgess was living in Rome in the early 1970s. Eco, who worked as a radio producer, interviewed Burgess in connection with Joysprick, a book about the language of James Joyce. Later on, Burgess wrote favourable reviews of a number of Eco’s books, including The Name of the Rose, Faith in Fakes, and Foucault’s Pendulum. When Jean-Jacques Annaud was planning his film version of The Name of the Rose (starring Sean Connery and Christian Slater), Eco wrote to Burgess and told him that he would be the ideal screenwriter for the project. Despite Eco’s strong wishes, the script credit for the 1987 film was shared by Gérard Brach, Andrew Birkin, Howard Franklin and Alain Goddard.

TWO: Federico Fellini paid him in pianos.

In 1976 Burgess was hired to work as the English dialogue consultant on Federico Fellini’s Oscar-winning film Casanova, starring Donald Sutherland in the title role. Burgess was worried about having to pay Italian income tax on his fee, so he agreed with Fellini that his payment would take a different form. After Burgess had completed his work on the script, Fellini arranged for a new Steinway piano to be delivered to his house in Bracciano, near Rome. He was filmed playing this piano in 1982, and it is now with his other musical instruments at the Anthony Burgess Foundation in Manchester.

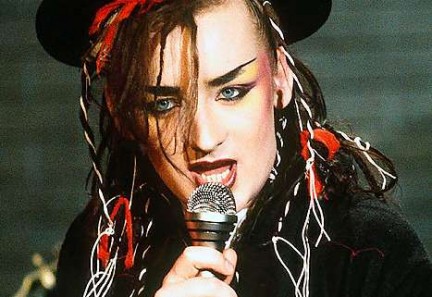

THREE: He announced the death of Boy George by mistake.

In 1986 Burgess was asked to write a newspaper article about Boy George, front-man of the eighties band Culture Club, who was reported (wrongly, as it turned out) to be close to death because he was said to be using non-prescription drugs. In a piece titled ‘The Killing of Boy George’, published in the Daily Mail on 4 July 1986, Burgess claimed that, as a musician, Boy George was inferior to the Beatles (whom he’d always hated) and said that he would be ‘sorry to see him die.’ Responding to these reports of his demise, Boy George hit back in his autobiography, Take It Like a Man (1995), where he said that Burgess’s premature obituary was one of the nastiest things ever written about him. On balance, it seems unlikely that Burgess had ever heard of Boy George or Culture Club before he agreed to write the article.

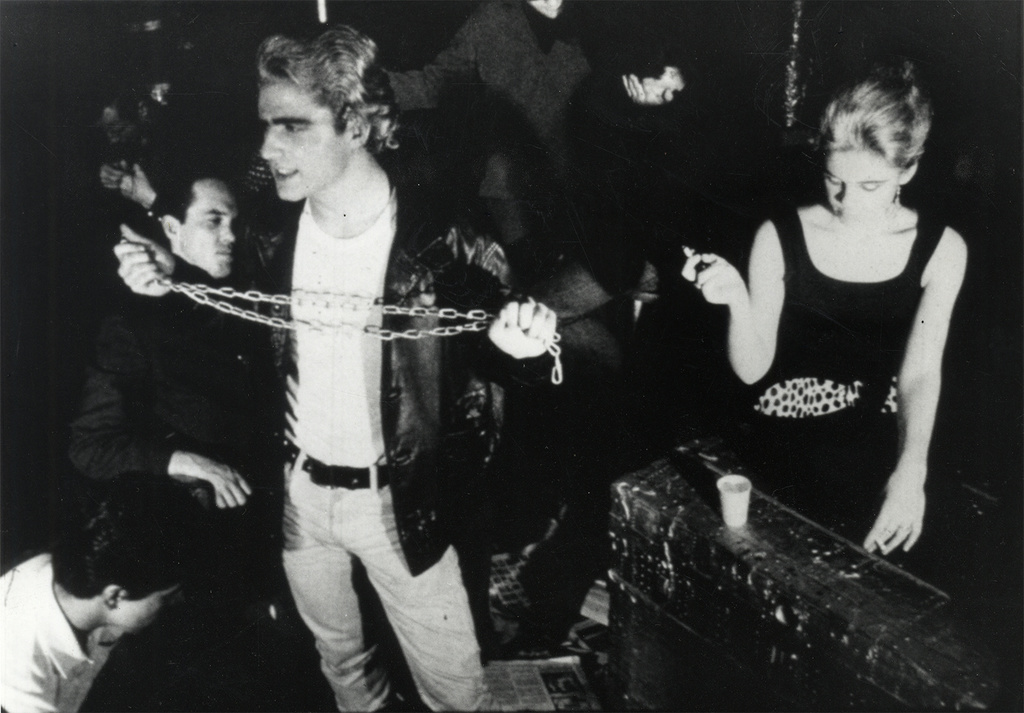

FOUR: Andy Warhol made a pirate film of A Clockwork Orange.

In 1965 Andy Warhol and his associates at the Factory in New York made an underground film version of A Clockwork Orange under the title Vinyl. Shot in three takes on 16mm black-and-white film, the 66-minute movie featured appearances from Factory regulars Gerard Malanga and Edie Sedgwick. There was a script written by Ronald Tavel, but few of the cast bothered to learn their lines. As Warhol did not own the rights in Burgess’s novel, Vinyl became the first of several pirate adaptations of A Clockwork Orange. When The Velvet Underground played at Rutgers University in 1966, Vinyl was used as a back-projection for their performance. Generally agreed to be one of the worst movies ever made, Vinyl has now been released on DVD by the Andy Warhol Foundation.

FIVE: He didn’t own a bed.

When Burgess and his wife Liana bought their apartment in Monaco in 1975, there was a dispute with the authorities about parking in the street outside. He bought a mattress and waited for his bed to be delivered. As he wrote in a non-fiction book, On Going to Bed: ’A double bed was in the remover’s van, but the local police would not permit that van to be parked in order that the process of moving could be consummated. I had to send this van into the open country, buy a small property nearby, and have the furniture transferred thereto.’ Burgess and his wife spent more than six years with a mattress but no bedstead. But they did not repine. ‘I have come to prefer the mattress on the floor to the true bed,’ he wrote. ‘You cannot fall out of it.’

SIX: His favourite food was Lancashire hotpot.

After the death of his first wife in 1968, Burgess began to cook and found that he enjoyed it. Like his fictional character Enderby, he had a nostalgic attachment to traditional British stews. This is his recipe for a Lancashire hotpot: ‘Into a family-sized, brown, oval-shaped dish with a lid, you place the following ingredients: best end of neck of lamb, trimmed of all fat; potatoes and onions thickly sliced. These go in alternate layers. Season well, cover with good stock, top with oysters or, if you wish, sliced beef kidneys. There is no need for officious timing: you will know when it is done. Serve with pickled red cabbage and a cheap claret.’

SEVEN: He wrote a film for Burt Lancaster, based on one of Freud’s case histories.

Burt Lancaster was the star of Moses the Lawgiver, scripted by Burgess and broadcast worldwide in 1973. In October 1975 Lancaster travelled to Iowa City to hear the world premiere of Burgess’s Symphony in C. While he was in town, he proposed that Burgess should write a film for him based on the life of Daniel Paul Schreber, a German high court judge who is the subject of a psychoanalytical case history by Sigmund Freud. Lancaster wanted to play Schreber, who suffered from delusions and believed that he had been given a divine mission to repopulate the world with a new race of angelic beings. Burgess completed two drafts of the script, but sadly the Schreber film never went into production. This was not the end of Lancaster’s association with Burgess: he went on to play Pope Gregory X in the television series Marco Polo, written by Burgess and broadcast in 1982.

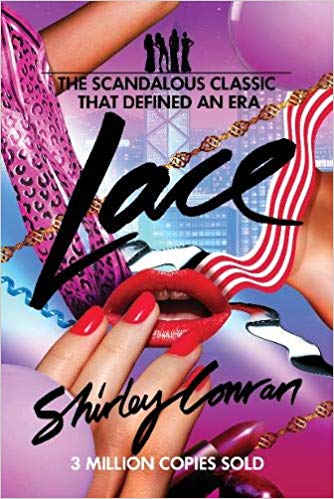

EIGHT: He was rumoured to be the ghost-writer for Shirley Conran’s best-selling novel, Lace.

Burgess got to know Shirley Conran, a former Sunday Times journalist (already famous for Superwoman [1975], a book about household management), when she moved to Monaco to write her first novel. Burgess was never able to scotch the rumour that he’d had a hand in Conran’s Lace, which was published in 1982 and later adapted as a TV mini-series. He wrote in the second volume of his memoirs that Conran ‘came regularly in the evenings to No. 44 rue Grimaldi [his address in Monaco] and I could not take seriously the instalments she brought me to read and, of my goodness, correct, improve, respell, reparagraph.’ When the book was about to be published, Burgess wrote in a letter to Conran: ‘I think it might even be considered indiscreet to mention help. So please don’t bring [my name] into it.’

NINE: He was banned from the Whitworth Art Gallery.

When he was a schoolboy, Burgess paid a visit to the Whitworth Art Gallery on Oxford Road in Manchester with some friends. He wrote later: ‘In the company of other kids I had sucked at the marble breast of a Greek goddess and [was] ejected by one of the curators.’ He claimed to have been banned from the gallery ‘for some time.’ Walking to school at Xaverian College from his home at 261 Moss Lane East, he passed the Whitworth Gallery every day. Eventually he summoned the courage to return, and he remembered the joy he felt when looking at the gallery’s collection of prints and drawings by William Blake. Many years after the unfortunate episode of the Greek goddess, it seems that all has now been forgiven. To mark the Burgess centenary in 2017, the Whitworth commissioned two artists’ films, based on the first and last volumes of the Enderby Quartet, and both films have been added to their permanent collection. The photograph shows Genesis by Jacob Epstein (1929-31) at the Whitworth.

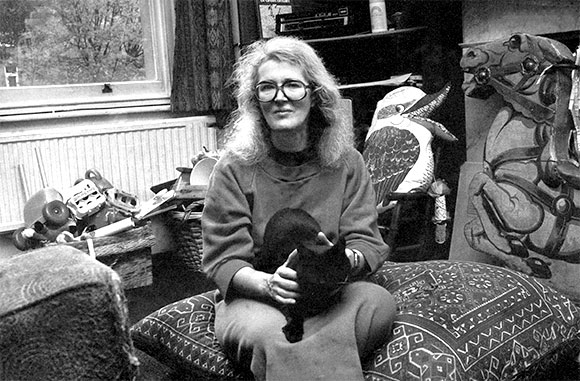

TEN: Angela Carter and Burgess were good friends.

Burgess was introduced to Angela Carter by his agent, Deborah Rogers. Impressed by her boldly original writing, he provided an endorsement for her first novel, Shadow Dance, which appeared on the front cover when the book was published in 1966: ‘I’ve read this book with admiration, horror, and other relevant emotions, including gratitude that we seem to have here a distinctive talent that’s going to be a major one.’ Carter wrote to thank Burgess and they arranged to meet shortly afterwards at his house in Chiswick. Although Carter moved to Japan and Burgess went to live in Malta, Italy and America, they maintained their literary friendship throughout the 1970s by exchanging letters, which are now in the Burgess and Carter archives. In later years they saw each other infrequently, but they were both present at the Bloomsday celebration in Dublin in 1982, an event which is mentioned in Carter’s book of essays and in Burgess’s memoir, You’ve Had Your Time. According to Carter’s biographer, Edmund Gordon, the friendship with Burgess ‘was Angela’s first literary alliance and she was “enormously pleased and flattered” by it.’

BONUS FACT: The cast of Quest for Fire were fluent in Ulam.

Burgess was asked to create an invented language called ‘Ulam’, based on Indo-European, for the film Quest for Fire, released in 1981. The film’s international cast, which included Ron Perlman, Nameer El Kadi and Rae Dawn Chong, did not share a common language. Nevertheless, they all became fluent in Ulam. Behind-the-scenes footage is available on the Quest for Fire DVD, showing the cast and crew communicating in Burgess’s invented language. A copy of the Ulam dictionary has survived in the archive of the Burgess Foundation, and there are plans to publish it in the near future.