The Anthony Burgess tapes: from Larry King to Nordic myths

-

Milena Schwab-Graham

- 23rd August 2021

-

category

- Blog Posts

The Foundation supports academic study into Anthony Burgess. In this second guest blog post (read the first one here), PhD researcher Milena Schwab-Graham writes about her work on the extensive Anthony Burgess cassette tape collection.

For the past few months, my work as a researcher for the ‘Anthony Burgess on Tape’ project has been a pleasurable introduction to the intricacies of remote archival work, his voice sounding out through digitised versions of cassette tape recordings held in the Burgess Foundation in Manchester. Listening to Burgess’s lectures, interviews and conversations has been a process of attuning one’s ears, not just to the sudden shifts in the cadence of his voice, which has a tendency to increase in volume on unexpected syllables, but also to the contradictions and eccentricities of his self-made narrative.

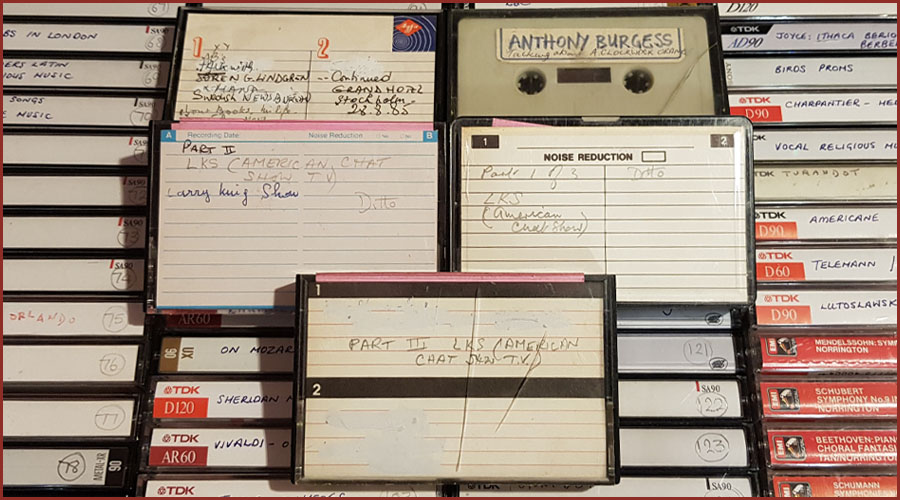

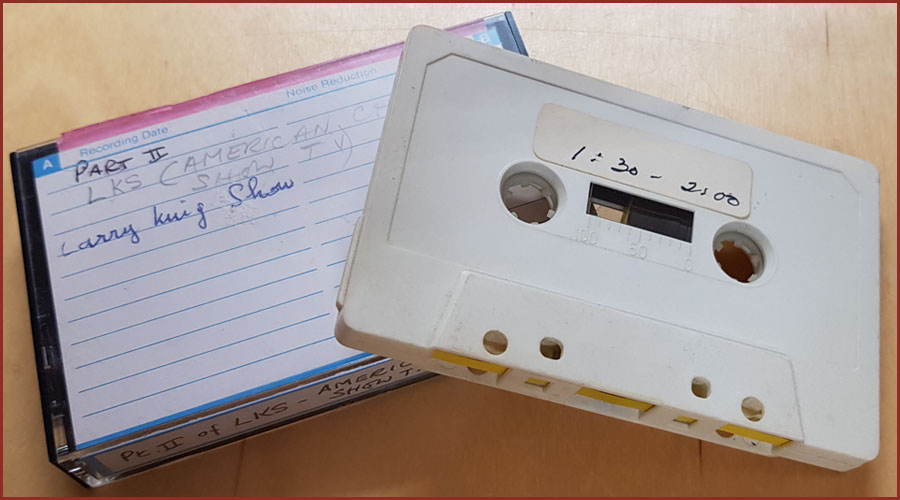

The recordings which I have been cataloguing for the project span the closing decade of Burgess’s life. They range from a commercial radio interview for the Larry King Show in June 1980 as part of the US press tour for Earthly Powers, to a recording of a lecture given in October 1991 for the Tate Gallery in London, which poses the question, ‘Can Art Be Immoral?’.

Certain life events become touchstones for Burgess’s conversations with journalists and talk show hosts in the US, UK, Canada and Sweden; these also resurface in his lectures, such as the three-part series which Burgess gave on ‘Modern Literature’ in March 1982. Throughout these recordings, Burgess makes repeated reference to his ‘terminal year’, 1959, in which he recalls receiving the diagnosis of an inoperable brain tumour. This, as he tells Larry King, was catalytic to his creativity, resulting in five novels being written in one year:

In the interview, Burgess is able to wryly comment that there was always “something fishy” about his terminal diagnosis, suggesting that its verisimilitude has been eclipsed by his substantial body of work. By 1980 this included close to two dozen published novels and numerous volumes of literary criticism.

The collection of recordings affords insight into the mind of a late-career polymath with a well-established reputation as a prolific writer of ambitious fiction, saturated with literary allusion, Joycean wordplay and Christian allegory. They show a writer at the height of his powers, marking a decade which begins with two of Burgess’ most allegorically layered novels, Earthly Powers (1980) and The Kingdom of The Wicked (1985), after which he embarked on a succession of works which gave suggestively and explicitly autobiographical accounts of his upbringing. These included The Pianoplayers (1986), a work of fiction with a female protagonist at its centre, but whose tone and setting are deeply rooted in the working-class musical culture of Burgess’ Manchester childhood, and the two volumes of his autobiography, Little Wilson and Big God (1987) and You’ve Had Your Time (1990).

Such works of Burgess’s inevitably look back to the past, and a pensive, retrospective outlook on his life and career resurfaces throughout the collection of recordings preserved from this period. When asked about the motivations for his pursuit of a working, creative life, by turns a writer, critic and composer, Burgess often dryly observes that he writes out of financial necessity foremost. Novel writing, and literary reviewing, as Burgess infamously did for the Yorkshire Post in the early 1960s, are disingenuously referred to as a ‘trade’ – a means of paying the bills.

However, the recordings in the collection present an altogether different perspective, as they reveal Burgess’ deeply held conviction in the necessity and difficulty of writing. As he attests in an earlier interview with Italian media some five years before his conversation with Larry King, Burgess regards autobiography as a form of catharsis:

Burgess’s creative endeavours thus enabled more than putting food on the table; crucially, his fiction writing and literary criticism, which I am especially interested in as a doctoral researcher in English literature, enabled Burgess to process difficulties in his own life, including his first wife Lynne’s miscarriage, as well as his apparent brain tumour diagnosis.

The recordings in the collection highlight Burgess’s abiding preoccupation with the processes of literary and musical composition. Burgess is quick to draw parallels between his experiences of adapting literature for the screen, and his work as a composer. This is particularly evident in the wide-ranging interviews which he undertook with the journalists Per Svensson and Soren G. Lindgren for Swedish media in August 1985, to coincide with the Swedish publication of his Biblical narrative, The Kingdom of the Wicked:

In typical fashion, Burgess’s conversation with Lindgren for the Swedish News Bureau about Christianity in The Kingdom of the Wicked soon becomes a freewheeling discussion about myth-making and Nordic mythology, with frequent interjections from Burgess’s second wife, Liana, on the etymology of European languages.

Recorded in the Grand Hotel, Stockholm, the conversation is interspersed with the background hubbub of the hotel restaurant, and the clink of spoons against coffee cups. Here, Burgess is in an especially playful mode, citing his love of the Asterix comic books and their use of Celtic mythology. Burgess punctuates the ongoing debate about the name of the Norse goddess Brunhilde’s horse by letting out an unexpected whinny:

Such moments of whimsy compound the enjoyment to be found in exploring the collection of recordings. Working as a researcher on this project has highlighted how Burgess moves between serious intellectual argumentation and mordant wit with apparent ease. However, his underlying preoccupation with the process of writing continues to shine through, whether Burgess is doing press for a recent work, or giving a public lecture.

It was this artfully obscured dedication to his craft which I became especially keen to pursue during my in-person visit to the Burgess archive in Manchester in July 2021, as I will discuss in my next blog post.

Milena Schwab-Graham is a PhD Student at the University of Leeds. Her research is funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council through the White Rose College of the Arts and Humanities. Read her previous blog post here.