The Clockwork Collection: Burgess on Kubrick’s ‘damned nuisance’ movie

-

Anna Edwards

- 27th May 2021

-

category

- Blog Posts

2021 marks the 50th anniversary of the first release of Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation of A Clockwork Orange, and 60 years since Anthony Burgess completed his most famous novel.

To celebrate the anniversary, we present an online series called The Clockwork Collection, with a focus on A Clockwork Orange.

Each month, we’ll be sharing a highlight from the Burgess Foundation’s archive. Expect literary manuscripts, vinyl, books, audio, journalism, music scores, photographs and more. For more information on the items discussed in the series, please contact our archivist.

The Clockwork Collection: Burgess talking about Kubrick’s ‘damned nuisance’ movie

The film has just been a damned nuisance. I am regarded by some people as a mere boy, a mere helper to Stanley Kubrick, the secondary creator who is feeding a primary creator, who is a great film director. This I naturally resent. I resent also the fact I am frequently blamed for the various crimes which are supposed to be instigated by the film.

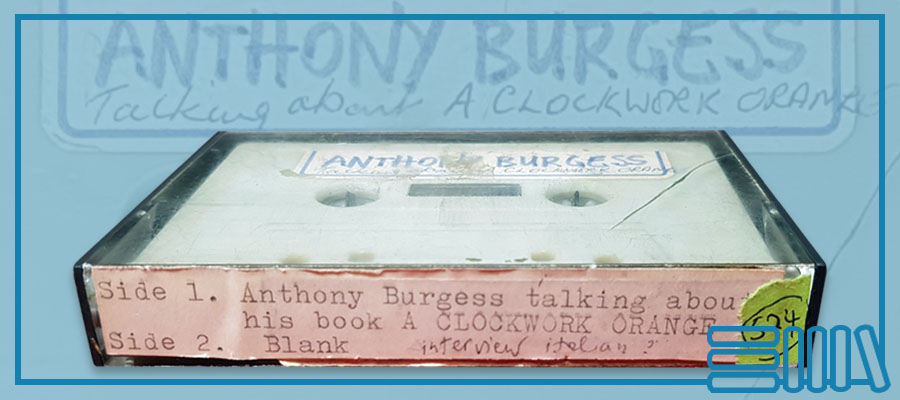

So replied Anthony Burgess when asked to describe the effect of Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation of A Clockwork Orange in a recorded interview with Italian media in 1974 or 1975 (audio clip above). Much of the context of the interview is unknown, and the date has been determined through internal evidence only — Burgess refers to himself as being 57 years old — rather than by referring to supporting documentation.

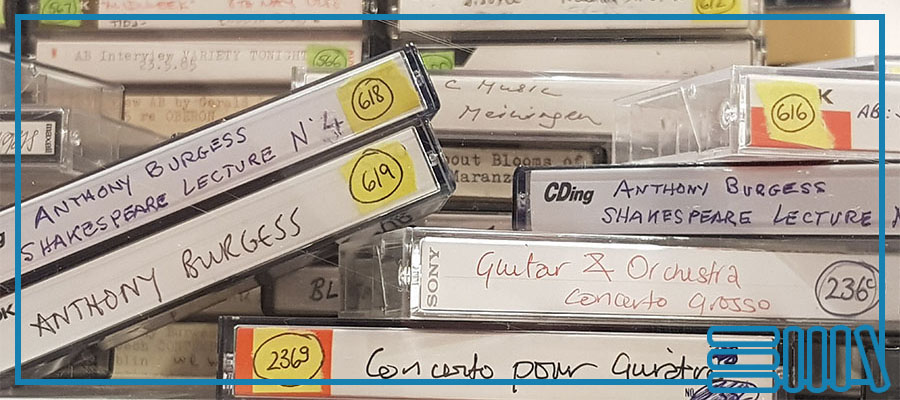

A recording of the interview survives in our audio cassette collection, and it is one of a number of sources within our archive that help to chart Burgess’s complicated relationship with A Clockwork Orange.

Early in the interview, Burgess is asked about his inspiration for A Clockwork Orange and its significance to him. His reply emphasises both the specific set of circumstances in which the book was created, and also that its central theme is common to many of his works.

He touches on the story’s autobiographical elements, its linguistic originality, his growing belief in the late 1950s that the state threatened to encroach on an individual’s right to freedom of choice, and the book’s core message ‘that man is free, that man was granted the gift of free will, and that he can choose.’ The novel’s greatest value to Burgess was, so he tells the interviewer, therapeutic. It allowed him to work through certain events in his life ‘and to purge them, to cathartise the pain, the anguish, in a work of art.’

He touches on the story’s autobiographical elements, its linguistic originality, his growing belief in the late 1950s that the state threatened to encroach on an individual’s right to freedom of choice, and the book’s core message ‘that man is free, that man was granted the gift of free will, and that he can choose.’ The novel’s greatest value to Burgess was, so he tells the interviewer, therapeutic. It allowed him to work through certain events in his life ‘and to purge them, to cathartise the pain, the anguish, in a work of art.’

Whatever the novel’s significance to Burgess, it was not an instant hit with audiences when it was published in 1962. It sold poorly despite the praise that authors such as Kingsley Amis had given it, and by the mid-1960s it had only sold 3872 copies. It was the release of Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation in 1971 that brought the work to a mass audience and increased its notoriety. The film generated a series of hostile reviews, articles and letters in the press, and a number of local councils in England refused to give permission for the film to be screened in their areas.

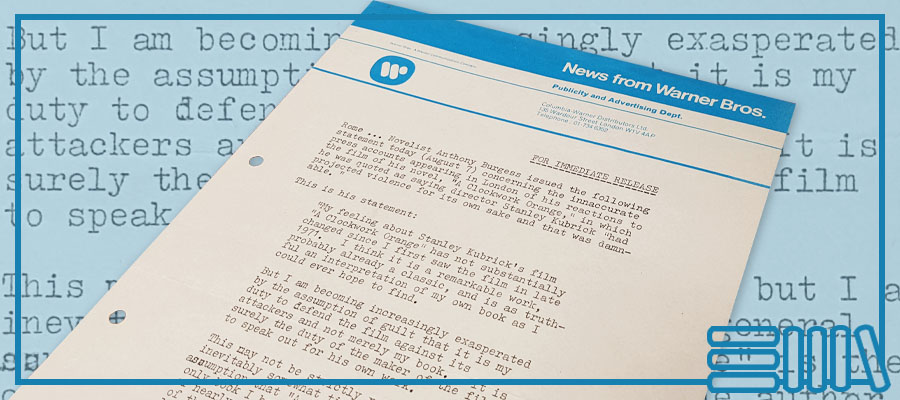

Burgess reviewed the film enthusiastically for the Listener in February 1972, describing it as ‘technically brilliant, thoughtful, relevant, poetic, mind-opening.’ This sentiment was echoed in a later press release, issued by Warner Brothers on Burgess’s behalf, in which he described the film as ‘a remarkable work, probably already a classic.’

A note of growing frustration was, however, now becoming apparent, perhaps fuelled by Kubrick’s reluctance to participate in the film’s press tour. Burgess commented: ‘I am becoming increasingly exasperated by the assumption of guilt that it is my duty to defend the film against its attackers and not merely my book’ and ‘I am inevitably somewhat tired of the general assumption that “A Clockwork Orange” is the only book I have written.’

These issues — that A Clockwork Orange came to overshadow his other works, and that he was frequently called on to defend Kubrick’s film and to talk about violence in the media — were to prove an ongoing source of annoyance for Burgess.

It was in this general climate of opinion that Burgess’s recorded interview with the Italian press took place in 1974-5 and, unsurprisingly, both of his main frustrations with the film are evident. He is irritated that ‘Out of the thirty odd books I have written this is often the only book of mine which is known,’ and he rejects the idea that A Clockwork Orange should be blamed for having caused any of society’s ills.

Referring to the Bible and several works by Shakespeare, he argues that art cannot be held culpable for violence in society. Evil, he says, is an aspect of life which art merely presents in a particular shape or form; it cannot be held responsible for it. As he puts it, ‘The work of art merely takes life as it is and shows life as it is and that’s the end of its duty.’

For all of Burgess’s resentment however, it would be overstating it to claim that he ever actively disliked his novel or, indeed, that he ever rejected Kubrick’s film. He was pragmatic enough to recognise that ‘no doubt a lot of people will want to read the story because they’ve seen the movie — far more than the other way round’ (‘Juice from a Clockwork Orange’, 1972), and he developed a friendly creative relationship with Kubrick in the years immediately following the film’s release.

Read: Clockwork Controversies – Did Anthony Burgess like Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange?

He would repeatedly return to A Clockwork Orange in subsequent years, turning it into a stage play in 1987, writing numerous articles and delivering lectures about it, and even writing a novel based on the production of the film, titled The Clockwork Testament. Much of this material can be explored in the Burgess Foundation’s archive.

At just over 35 minutes, the recorded interview is about far more than A Clockwork Orange. Burgess mentions, in passing, several of his current projects, such as Moses, Earthly Powers, a television series about the life of Shakespeare, and a film about Beethoven’s relationship with his nephew. There are also questions about his views on contemporary society, human nature, and religious belief.

The interviewer ends by asking Burgess if he has a message for mankind. His reply is that it is not the job of an artist to put one forward. He says: ‘it is merely the task of the literary creator, like the musical creator, to produce shapes, structures, which will be satisfying in themselves and which need not necessarily have any direct relationship to life as we live it at the moment’ (audio clip below).

This recorded interview is part of a collection of audio cassettes which are being catalogued as part of the ‘Anthony Burgess on Tape’ project. We thank Milena Schwab-Graham for helping to make this material accessible.