The Clockwork Collection: Burgess’s screenplay for A Clockwork Orange

-

Andrew Biswell

- 6th August 2021

-

category

- Blog Posts

-

tagged as

- A Clockwork Orange

- The Clockwork Collection

2021 marks the 50th anniversary of the first release of Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation of A Clockwork Orange, and 60 years since Anthony Burgess completed his most famous novel.

To celebrate the anniversary, we are presenting an online series called The Clockwork Collection, with a focus on A Clockwork Orange.

Each month we’ll be sharing a highlight from the Burgess Foundation’s archive. Expect literary manuscripts, vinyl, books, audio, journalism, music scores, photographs and more. For more information on the items discussed in the series, please contact our archivist.

The Clockwork Collection: Burgess’s screenplay for A Clockwork Orange

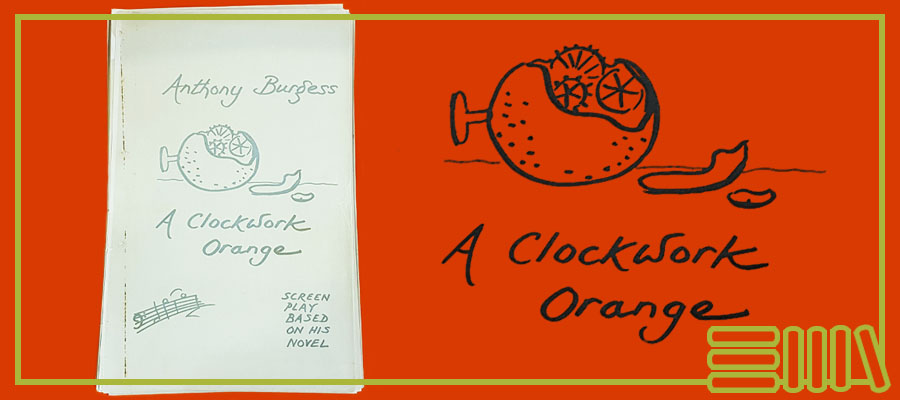

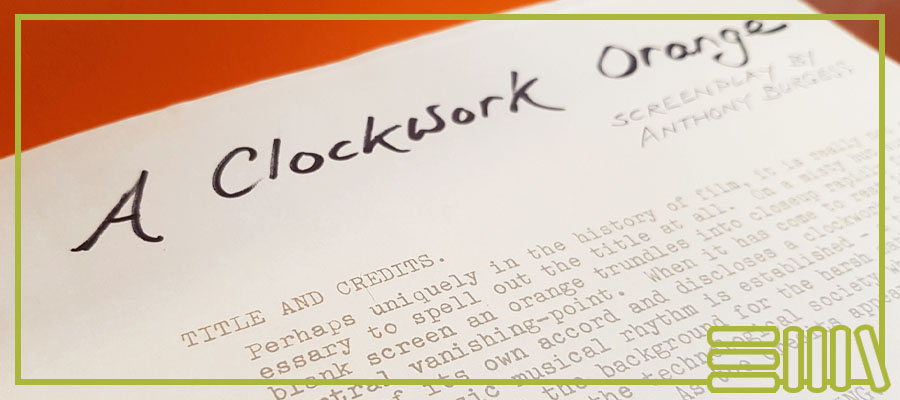

Anthony Burgess’s screenplay adaptation of A Clockwork Orange, written in 1969 and never filmed, runs to 89 typewritten pages. There is also a handwritten title page, decorated with a doodle of a clockwork orange by the author himself.

Burgess originally sold the moving-image rights in his novel to the entrepreneurs Si Litvinoff and Max Raab in 1966. Around this time, Litvinoff and Raab acquired the film rights in a number of other literary properties. The most successful of these deals was for the novel Walkabout by James Vance Marshall, translated to the big screen by the director Nicholas Roeg in 1971, with a screenplay by Edward Bond.

Burgess was neither the first nor the last screenwriter to make an adaptation of A Clockwork Orange. Ronald Tavel used some of the teenage violence and brainwashing material from the novel in his script for Andy Warhol’s low-budget pirate film Vinyl, shot in two takes at the Factory in New York in 1965. This was followed by another screenplay by Michael Cooper and Terry Southern, submitted to the British Board of Film Censors in 1967 and rejected on the grounds that the scenes of cruelty, ‘obscenity’ and violence would prevent the film from being approved for exhibition in British cinemas.

Two years later, Litvinoff and Raab invited Burgess to write his own script. By 1969 it seemed that the climate of censorship was beginning to change, and Burgess felt confident enough to include references to intravenous drug-use and implied violence against children in his adaptation, which deviates from the novel in many important respects.

The screenplay opens with an animated title sequence, in which a cartoon orange splits in half and reveals its clockwork interior. Animated titles were a common feature of British films in the 1960s — such as The Pink Panther (see below), directed by Blake Edwards, and the James Bond series.

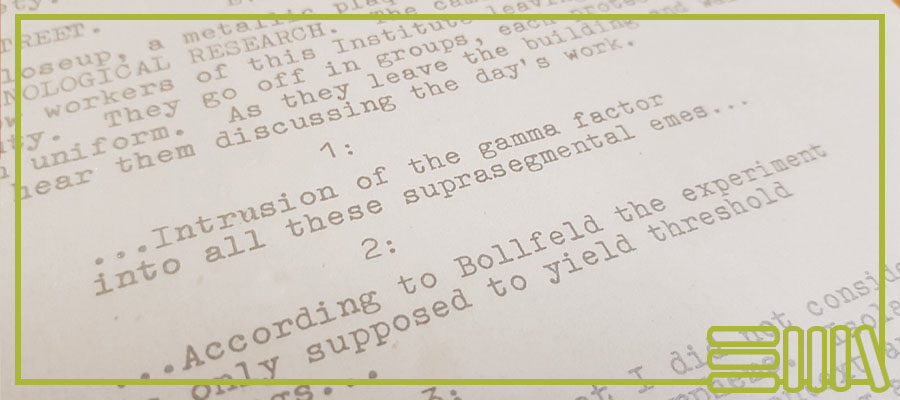

The action begins in the futuristic State Institute of Socio-Technological Research, where scientists with Germanic names are working on the chemical conditioning process that Alex will undergo later in the story. Music plays a central role in this version of the film: Burgess gives us images of a metallic, highly mechanised future, which are accompanied by ‘arid but complex’ music.

When we meet the teenage gang-members, they are listening to pop songs with Nadsat lyrics on a ‘transistor radio’. They are dressed like the droogs in the book, with white cravats and exaggerated codpieces. Alex himself is first seen in his bedroom, listening to vinyl records of music by Mozart and other fictional composers, such as Jeremiah Pertslob. There is a poster of Beethoven on his wall.

Burgess indicates that Alex should be sympathetic to the audience, appealing ‘to something in the darker reaches of our minds, our own frustrated ids.’ In this version, Alex puts on a Beethoven mask when he goes out for an evening of crime.

When the droogs visit the house of a writer and his wife, the name of the writer is changed from ‘F. Alexander’ in the novel to ‘Anthony Burgess’ in the screenplay. This underlines the metafictional element, also present in the novel, whereby the fictional author is writing a book titled ‘A Clockwork Orange’ — not a novel, but an absurdly long-winded political tract. In the screenplay, Burgess takes care to spell out the meaning of his title, which is never explained in Kubrick’s film.

The most significant deviation from the novel comes at the end of Burgess’s script. Alex has escaped from the clutches of Mr Burgess and his political friends by attempting suicide. Patched up in hospital, he receives a visit from the Minister of the Interior, who tells him that the conspirators have been locked up. Alex and the Minister agree to be friends. He listens to Beethoven and fantasizes about committing acts of ultra-violence.

In other words, Burgess and Kubrick both choose to end the film at exactly the same point (the end of chapter 20 in the novel), with the words ‘I’m cured, all right.’ The decision to conclude the film here undermines Burgess’s later claim that Kubrick spoiled his story by omitting the final chapter.

Kubrick said that he had not been influenced by any other versions of the screenplay when he scripted his film: he claimed to have worked directly from Burgess’s novel. But he had certainly read the Burgess script, and it may have informed his ideas about the structure of the story.

The 1969 screenplay, written while Burgess was living in Malta, is a key document for any researcher who wants to understand the history of A Clockwork Orange and its multiple adaptations for stage and screen. We expect that it will be made more widely available soon. In the meantime, researchers can read it on-site in the Burgess Foundation’s reading room.

Only two other copies of the 1969 screenplay are known to exist. One of these, lightly annotated by Kubrick himself, is in the Stanley Kubrick Archive at the University of Arts, London. A third copy, formerly the property of Si Litvinoff, has now disappeared after being offered for sale by a manuscript dealer in Budapest in 2018. The asking price was $15,000 US dollars.