The Clockwork Collection: Clockwork oranges are ticking bombs

-

Andrew Biswell

- 30th March 2021

-

category

- Blog Posts

2021 marks the 50th anniversary of the first release of Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation of A Clockwork Orange and 60 years since Anthony Burgess completed his most famous novel.

To celebrate the anniversary, we present an online series called The Clockwork Collection, with a focus on A Clockwork Orange.

Each month, we’ll be sharing a highlight from the Burgess Foundation’s archive. Expect literary manuscripts, vinyl, books, audio, journalism, music scores, photographs and more. For more information on the items discussed in the series, please contact our archivist.

The Clockwork Collection: Clockwork Oranges Are Ticking Bombs

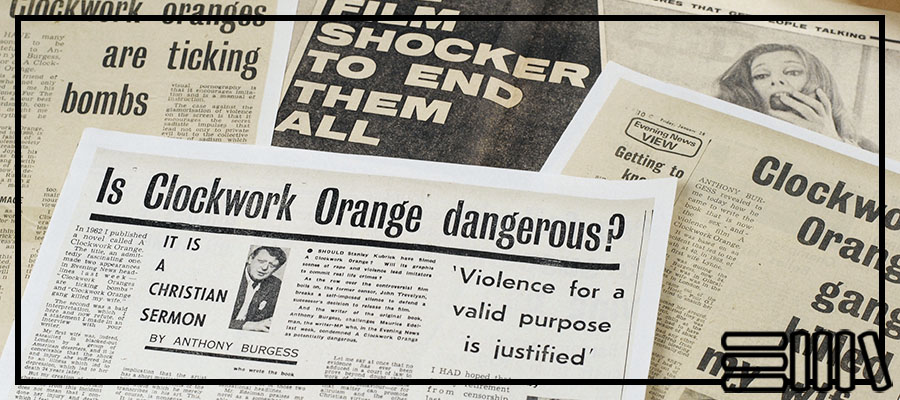

The archive of the Burgess Foundation contains a large number of press cuttings relating to the cinema release of Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation of A Clockwork Orange — from its first public screening in New York in December 1971 to the general release of the film in Europe in January 1972.

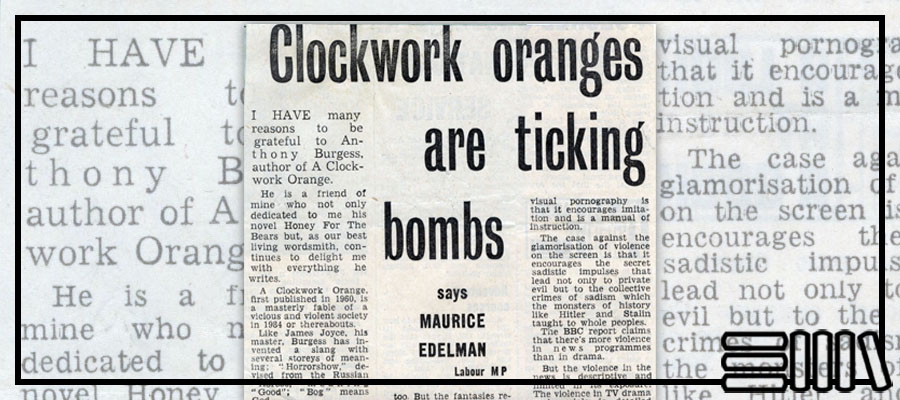

One of the responses which lodged in Burgess’s memory was an article by his friend Maurice Edelman, the Member of Parliament for Coventry North, published under the headline ‘Clockwork Oranges Are Ticking Bombs’. This was one of a number of strongly-worded opinion pieces which appeared in the British press in the wake of the film’s release.

Born in Cardiff to a Jewish family in 1911, Maurice Edelman was well known as a journalist before he entered politics. An accomplished visual artist and a gifted linguist, he learned Russian when he visited the Soviet Union in 1938, and later wrote about Russian affairs for the New Statesman and the Guardian.

After working as a war correspondent and reporting on D-Day for the Picture Post, he won a seat for the Labour Party in the General Election of 1945. He remained an MP until the end of his life, and he was much concerned with resisting the corrupt allocation of government jobs. Edelman combined the careers of novelist, playwright and politician in ways which drew comparisons with his hero, Benjamin Disraeli. He was a francophile and a member of the French Legion of Honour.

Burgess was introduced to Edelman by Sir Charles Snow, and he reviewed one of Edelman’s novels, The Minister, for the Yorkshire Post on 21 July 1961. Later on, they corresponded about two other novels, The Fratricides and The Prime Minister’s Daughter.

Edelman was the vice-chairman of the British Council, and his archive at Warwick University includes a copy of Burgess’s pamphlet, The Novel To-Day, published by the British Council in 1963. In the same year, Burgess dedicated his novel Honey for the Bears, set in Leningrad, to Edelman, and he described his friend as the ‘onlie begetter’ of the novel — an echo of Shakespeare’s dedication to the first edition of his Sonnets.

January 1972 was a time of tension and unrest on the streets of Britain. The coal miners’ strike had resulted in widespread power cuts and the government imposition of a three-day week in British factories. Meanwhile there was violence on the streets of Northern Ireland, which culminated in the shooting of 26 unarmed civilians by British soldiers on 30 January 1972. These events became known as Bloody Sunday or the Bogside Massacre.

Concerns about the possible effects of violent films were magnified in this atmosphere of political crisis. The Home Secretary of the day, Reginald Maudling, demanded a private screening of A Clockwork Orange after comment from the press that the film should not have been given a certificate by the British Board of Film Censors (BBFC).

Maurice Edelman’s article appeared on 27 January 1972 in the Evening News, a broadsheet London newspaper which later merged with the Evening Standard. Edelman began by declaring his admiration for Burgess as a highly original writer. Turning his attention to Kubrick’s film, he wrote:

Why do I feel that this film, brilliantly directed, beautifully photographed and superbly acted, will damage rather than improve society? The answer is that, despite Kubrick’s intentions, the film stimulates for two and a half hours an appetite for sadistic violence with that instantaneous communication which visual art uniquely offers. The flailing bicycle chain, the flick-knife, the boot in the groin are the bass to the sexual treble of multiple rape.

He went on to say that graphic films and television programmes had become ‘a night school of violence with a huge number of young pupils.’ Burgess was displeased to see his friend describing Kubrick’s film as being about ‘the joys of bashing to Beethoven.’ This article was part of the wider media response to the film, which Burgess went on to satirise in his next novel, intended as an answer to critics of the book and film versions of A Clockwork Orange.

In The Clockwork Testament, published in 1974, Burgess responds directly to the charge that violent films might cause copycat violence among their audiences. His counter-argument, voiced by the poet F.X. Enderby to the studio audience of a New York television chat show, is that evil exists in the bigger world, and that it is not called into being by books and films which depict it within the frame of art. Burgess’s arguments were unlikely to influence Maurice Edelman, who was regarded as an expert on (among other subjects) the film industry, the treatment of alcoholism, and the rehabilitation of ‘habitual drunken offenders’.

Edelman died suddenly in December 1975, aged just 64. He was remembered in a Times obituary for his ‘debonair appearance, a ready smile and an equally ready wit’. The Minister was reprinted in 1994 with a new introduction by Roy Jenkins, but none of his other books are in print today.

In many respects Maurice Edelman was a Burgessian figure — both were passionate Europeans with a broad knowledge of culture in general — and there are many points of intersection in their range of interests. Their friendship was based on a love of languages and a shared interest in Russia.

Unfortunately, the Evening News article seems to have ended their friendship. It is clear from Burgess’s account of Edelman’s article — which he described as an ‘attack’ — that he was still licking his wounds when he came to write his autobiography eighteen years later.