The Clockwork Collection: From Russia with Nadsat

-

Anna Edwards

- 29th January 2021

-

category

- Blog Posts

2021 marks the 50th anniversary of the first release of Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation of A Clockwork Orange, and 60 years since Anthony Burgess completed his most famous novel.

To celebrate the anniversary we are launching a new online series, with a focus on A Clockwork Orange.

Each month, we’ll be sharing a highlight from our archive. Expect literary manuscripts, vinyl, books, audio, journalism, music score, photographs and more. For more information on any of the items referred to in the series, please contact our archivist.

The Clockwork Collection: From Russia with Nadat. In which we examine Burgess’s Russian-English dictionaries and ‘Teach Yourself’ books.

In the summer of 1961 Anthony Burgess and his wife Lynne felt in need of a holiday, and Leningrad was an appealing, if unusual, destination. Passenger liners sailed regularly from Tilbury Docks, near London, to Leningrad (now known as St Petersburg), calling at Copenhagen and Stockholm en route. Burgess and Lynne made plans to travel on board the Alexander Radishchev in June 1961.

As Andrew Biswell explains in his biography, The Real Life of Anthony Burgess, Burgess’s motives for visiting Leningrad appear to have been mixed: a combination of literary, linguistic and cultural curiosity, along with a wish to gather material for a novel and a possible non-fiction book. The publisher William Heinemann offered to advance his travel expenses and offset them against future royalties.

Burgess learnt basic Russian for the trip and he acquired a number of Russian dictionaries, primers, and ‘teach yourself’ guides with which to meet this challenge. Many of these survive in the Burgess Foundation’s book collection, including the following volumes:

- Teach Yourself Books: Russian (English Universities Press, 1958), inscribed with Burgess’s name: ‘Иван Вiльсон’

- A Progressive Russian Grammar (Pitman and Sons, 1951)

- Russian-English, English-Russian Pocket Dictionary (Harrap, 1942)

- Russian: The 200 Basic Words on 7-inch vinyl (undated)

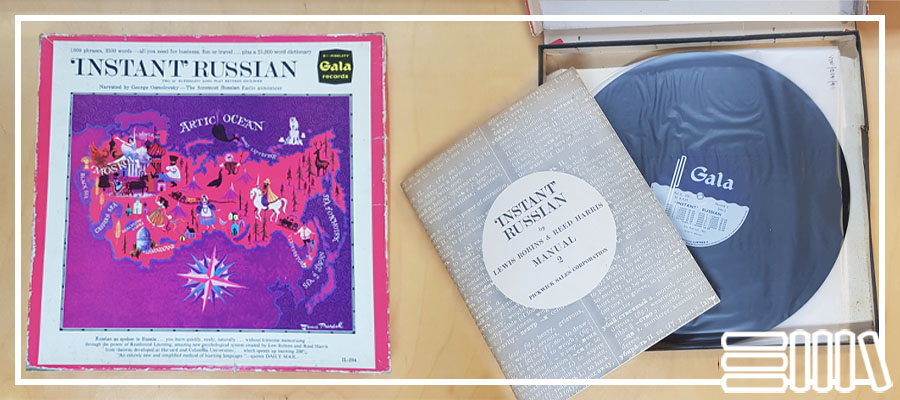

- Instant Russian, a 12-inch vinyl, dated 1959

To these can be added further books held at the Anthony Burgess Centre at the University of Angers in France. Examples include:

- Learning Russian (Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1960)

- Collins Russian Gem Dictionary (Collins, 1958), inscribed ‘Ivan Vilson’ in Cyrillic by Burgess.

- Getting along in Russian: A Holiday Magazine Language Book (Bantam Books, 1960)

- The Penguin Russian Course (Penguin, 1961)

This material is significant, not only because of the contribution it makes to our understanding of Burgess as a learner of languages, but also because it underpins much of the originality of A Clockwork Orange, providing it with one of its most innovative and memorable aspects. ‘Nadsat’, the invented slang spoken by Alex, the novel’s protagonist, emerged from Burgess’s intensive study of Russian.

Burgess began working on A Clockwork Orange in early 1961, but he grappled with what he called an ‘insoluble problem’: how to establish the voice of the book’s teenage narrator. In You’ve Had Your Time, he writes:

The story had to be told by a young thug of the future, and it had to be told in his own version of English. This would be partly the slang of his group, partly his personal idiolect. It was pointless to write the book in the slang of the early sixties: it was ephemeral like all slang and might have a lavender smell by the time the manuscript got to the printers.

As Burgess began to study Russian, it occurred to him that he had found a solution to this problem: the novel could be narrated in an invented slang which would be a hybrid of English and Russian, with strong elements of Cockney rhyming slang. The suffix used for the numbers 11 to 19 in Russian, ‘nadsat’, would give the teenage dialect its name.

According to Burgess, the language was intended ‘to turn A Clockwork Orange into a brainwashing primer. You read the book […] and at the end you should find yourself in possession of a minimal Russian vocabulary — without effort, with surprise.’

Nine of the ten most frequently used words in the novel (listed below) are of Russian origin. However, Nadsat also incorporates other elements and influences, including Lancashire dialect, Elizabethan English, military slang, and biblical and literary references.

- veck

- viddy

- horrorshow

- malenky

- viddy

- goloss

- glazzy

- gulliver

- litso

In the end, Nadsat was not fixed in the language of the early 1960s. And it continued to develop long after the novel had been published, as is demonstrated by ‘new’ Nadsat words which appear in Burgess’s 1987 stage adaptation, A Clockwork Orange: A Play with Music.

In her 2018 article titled Subliterary Modes of Earning the Odd Pound, Anna Aslanyan asks how good Burgess’s Russian was, noting that sometimes he described himself as fluent and at other times as being armed with only a rudimentary vocabulary.

Whatever the truth, it is clear that Burgess’s visit to Leningrad was as inspiring as he hoped it would be, providing material for another novel in addition to A Clockwork Orange — Honey for the Bears — and a number of magazine articles in which he described his impressions of the Soviet Union.