The Clockwork Collection: ‘The Clockwork Condition’ manuscript

-

Andrew Biswell

- 3rd November 2021

-

category

- Blog Posts

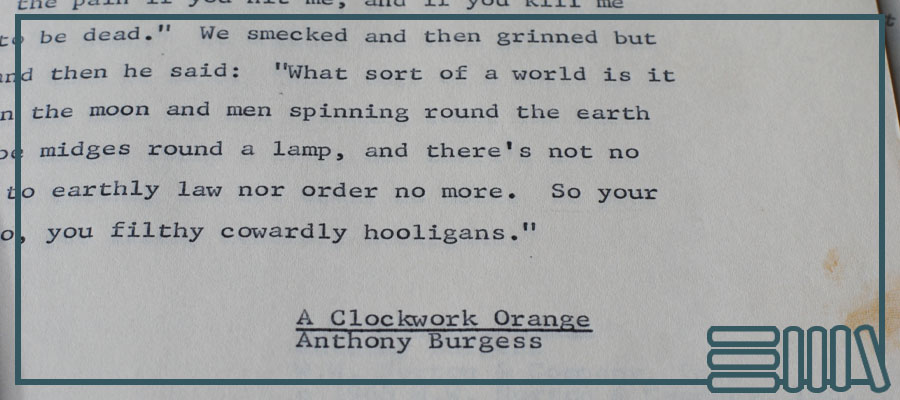

2021 marks the 50th anniversary of the first release of Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation of A Clockwork Orange, and 60 years since Anthony Burgess completed his most famous novel.

To celebrate the anniversary, we are presenting an online series called The Clockwork Collection, with a focus on A Clockwork Orange.

Each month we’ll be sharing a highlight from the Burgess Foundation’s archive. Expect literary manuscripts, vinyl, books, audio, journalism, music scores, photographs and more. For more information on the items discussed in the series, please contact our archivist.

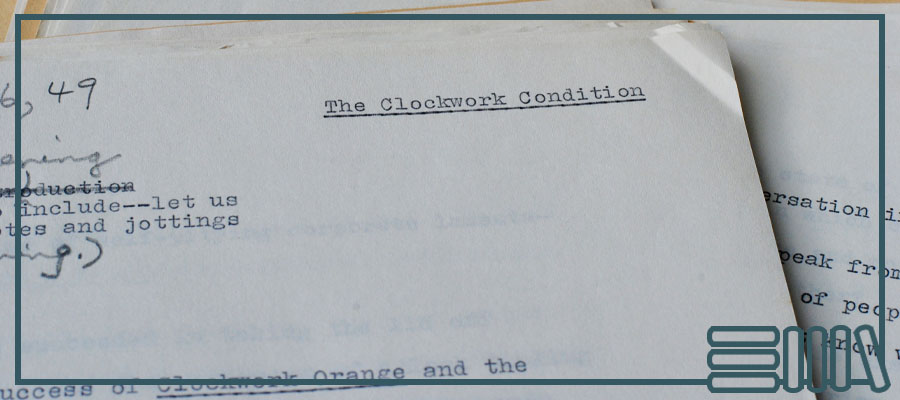

The Clockwork Collection: ‘The Clockwork Condition’ manuscript

One of the most tantalizing items in the Burgess Foundation’s collection of literary manuscripts is ‘The Clockwork Condition’, a series of notes, drafts and fragments which extends to 325 typewritten pages. The material, dating from 1972 and 1973, was written by Burgess, in collaboration with others, as an immediate response to Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation of A Clockwork Orange.

In January 1972 Warner Brothers flew Burgess to New York, where he spent several weeks publicizing the film on television, radio and in newspaper interviews. In mid-January he had his first meeting with Thomas P. Collins, a former Jesuit seminarian who had become a writer and book-packager. With his wife, Patricia Collins, he ran a company named Collins Associates, producing books, films and film-strips, normally with a religious theme, for the educational market.

Thomas Collins proposed that Burgess should write proposals for a series of American-themed novels which would be offered to publishers under a three-book contract. The idea of the scheme was to generate very large advances which would be divided between Collins and Burgess. As a prelude to the trilogy of novels, Collins wanted Burgess to write a short, illustrated non-fiction book under the title ‘The Clockwork Condition’, to capitalize on the worldwide publicity generated by Kubrick’s adaptation. The film had provoked widespread debates about the ethics of representing of sex and violence on screen, and it was banned in countries such as Ireland, Spain, South Africa and Brazil.

An outline of the unfinished book shows us exactly what Burgess and Collins had in mind. Borrowing its structure from Dante’s Divine Comedy, the work would be divided into three sections: ‘Infernal Man’, ‘Purgatorial Man’ and ‘Paradisal Man’. Taking the character of Alex from A Clockwork Orange as a starting point, Burgess proposed that his book would develop the themes of his earlier novel in the form of a 10,000-word philosophical essay about freedom, accompanied by 75 pages of black-and-white photographs. The resulting publication would be, as Collins put it (demonstrating his characteristic flair for hyperbole), ‘a major statement on the contemporary human condition.’ Collins pitched this book out to commercial publishers, and he received warm responses from publishing houses in London, Paris and New York.

The manuscript in the archive deviates quite substantially from the proposed three-part structure, and it is clear that the Dante concept was discarded at a fairly early stage in the development of the project. The next idea was to structure the book around a series of provocative quotations taken from interviews with Burgess. It is clear from Collins’s letters that he intended to tape-record additional conversations with Burgess in Rome, to supplement the existing interview material.

Burgess raised the stakes when he told Collins that the right length for the book would be 50,000 words, adding that unfortunately he was too busy to give it the attention it required. According to another revised outline of ‘The Clockwork Condition’, the third concept was to present a series of short pensées, similar in style and content to The Unquiet Grave by Cyril Connolly. Burgess had read Connolly’s book — a fragmentary journal in three parts, with quotations in English, French and Latin — while he was a soldier in Gibraltar during the Second World War, and he counted it among his favourite non-fiction books.

As Burgess went on trying out different ideas but failing to deliver his promised manuscript, Collins proposed another change of direction. Would Burgess be willing to write a kind of journal, to be published under the title ‘The Year of the Orange’? Collins enlisted William Weatherby, the New York correspondent of the Guardian newspaper, to assist with researching and compiling the new manuscript. Weatherby was a true original: he wrote about everything from boxing to ballet, and published a biography of James Baldwin and a book of his conversations with Marilyn Monroe. Weatherby prepared a list of interview questions, based on a careful reading of Burgess’s novels and his articles for the New York Times, with the aim of giving the book a more discursive and autobiographical flavour.

Eventually, in the summer of 1973, Burgess solved the conundrum by writing, in the space of about three weeks, a comic novel set in New York, in which he explores some of the thematic material he had intended to discuss in the ‘Clockwork Condition’ manuscript. This book is The Clockwork Testament, the third instalment in the adventures of the poet F.X. Enderby, published in 1974 with illustrations by the Quay Brothers. Within the novel, Enderby has written the script of a ultra-violent film, and he is invited onto TV talk shows, as Burgess himself had also been, to defend the film against accusations that it has caused copy-cat crimes.

The completion and delivery of this novel released Burgess from his contractual obligations to the publishers who had signed up for his non-fiction book. The abandoned manuscript of ‘The Clockwork Condition’ remained, disregarded, in his house in Bracciano until it was transferred into the Burgess Foundation’s archive in 2004.

Why did Burgess abandon ‘The Clockwork Condition’? One answer is that he was too busy with other, more lucrative, writing commissions in 1972 and 1973. His New York agent, Robert Lantz, had negotiated deals for him to write a variety of other projects for Hollywood and Broadway, including a novel about Napoleon Bonaparte, intended as raw material for a Kubrick film, and a stage musical about Houdini for Orson Welles.

The surviving ‘Clockwork Condition’ manuscript is a haphazard and rather skeletal collection of notes and fragments. Like all unfinished books, it is an invitation to a feast which turns out to be a menu but not the meal itself. Nevertheless, there is enough material in the files for readers to see what the bigger non-fiction book might have been, if only Burgess had had the time and inclination to complete it.