The Clockwork Collection: The origins of A Clockwork Orange

-

Anna Edwards

- 30th April 2021

-

category

- Blog Posts

2021 marks the 50th anniversary of the first release of Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation of A Clockwork Orange and 60 years since Anthony Burgess completed his most famous novel.

To celebrate the anniversary, we present an online series called The Clockwork Collection, with a focus on A Clockwork Orange.

Each month, we’ll be sharing a highlight from the Burgess Foundation’s archive. Expect literary manuscripts, vinyl, books, audio, journalism, music scores, photographs and more. For more information on the items discussed in the series, please contact our archivist.

The Clockwork Collection: The origins of A Clockwork Orange

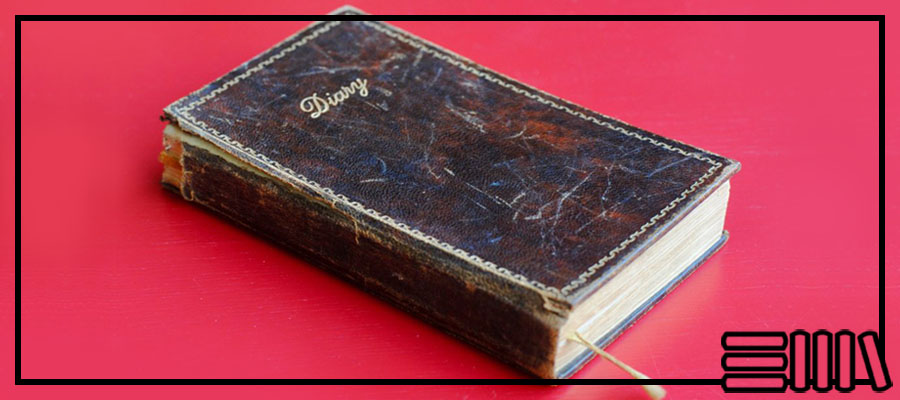

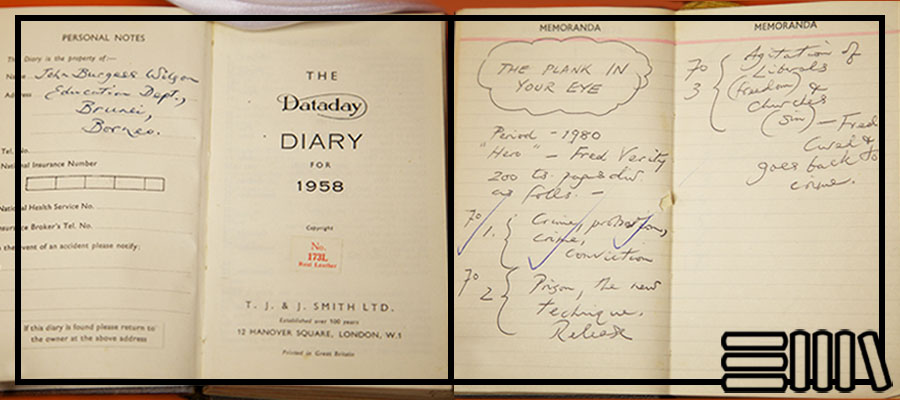

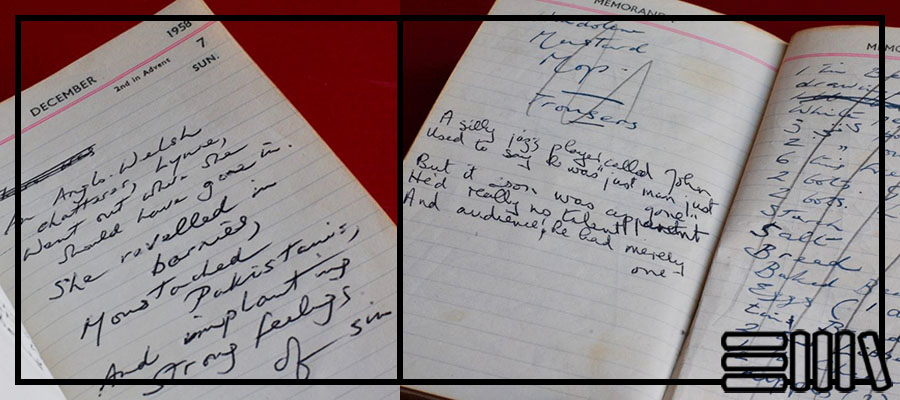

Burgess’s earliest surviving plan of A Clockwork Orange can be found in a small pocket diary within our Anthony Burgess archive, dating from 1958. The diary measures approximately five inches by three inches and is embossed with a gold design around the edge of its hardback cover. Scratches to the cover, and damage to its binding, reflect its heavy use.

The plan extends over three pages at the front of the diary and takes the form of brief lists and summary notes. The first two pages provide the most detail and reveal that Burgess envisaged a book of around 200 pages, to be divided into three sections of about seventy pages. The novel is to be set in 1980 and its anti-hero is a criminal named Fred Verity. ‘The Plank in Your Eye’ serves as Burgess’s working title, an allusion to Matthew 7:3-5 which forms part of the Sermon on the Mount:

Why do you look at the speck of sawdust in your brother’s eye and pay no attention to the plank in your eye? How can you say to your brother, ‘Let me take the speck out of your eye,’ when all the time there is a plank in your own eye? You hypocrite, first take the plank out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to remove the speck from your brother’s eye.

Burgess summarises each section of the novel as follows: part one will deal with Fred Verity’s crimes and eventual conviction; part two, his imprisonment, brainwashing, and eventual release; and part three will consider the agitation of liberal politicians who were concerned about freedom and churches concerned about sin.

Burgess’s opinion about the appropriate ending of A Clockwork Orange is much debated and it’s interesting to note that, in this early sketch, Burgess writes: ‘Fred cured & goes back to crime.’ In later years, Burgess would describe the novel as having been planned and written as a twenty-one-chapter entity which ends with its protagonist growing up and renouncing violence of his own accord. This early sketch reveals that Burgess initially intended the novel to conclude with Fred Verity remaining unredeemed.

As Burgess worked on the novel however, he appears to have become more uncertain about its ending to the extent that, as Andrew Biswell explains in The Real Life of Anthony Burgess, when Burgess completed his typescript in summer 1961, he was genuinely unsure about how it should conclude. The typescript (now held at McMaster University, Ontario) includes Burgess’s handwritten query at the end of chapter twenty: ‘Should we end here? An optional “epilogue” follows.’

The final page of Burgess’s early plan relates to section 2 of the novel and takes the form of a brief list. The title is now given as ‘A Clockwork Orange’:

A Clockwork Orange

Part II

(60/70 pages)1. Sermon, chaplain

2. Governor

3.

4.

5.

6.

(7.)

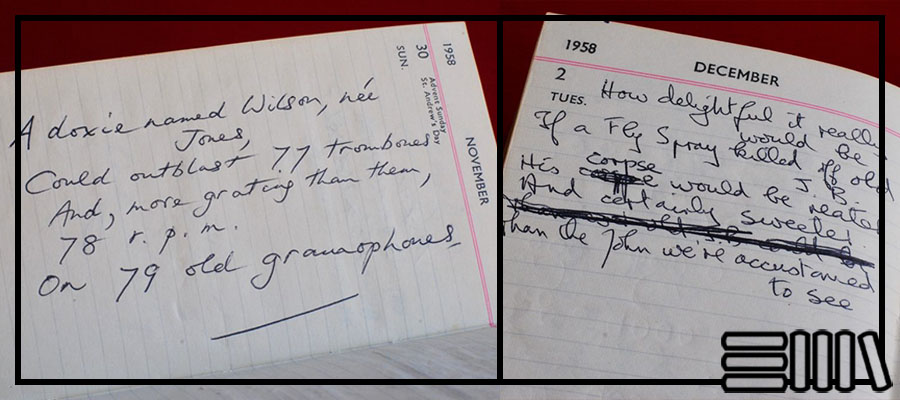

The 1958 diary is one of fourteen that survive in our collection and, like others within the series, contains a rich variety of content, including music scores, limericks, personal accounts, doodles / cartoons by Burgess, shopping lists, and notes towards a number of novels and other literary projects alongside A Clockwork Orange. Burgess appears to have used the diary as a notebook over a number of years after acquiring it in 1958; thus the date of the diary only indicates the earliest possible point at which Burgess could have created its content. (A handwritten inscription on the ‘Personal Notes’ page at the front of the diary confirms that Burgess acquired it while teaching in Brunei: ‘This diary is the property of John Burgess Wilson. Education Dept, Brunei, Borneo.’)

Despite Burgess’s claim that he wrote A Clockwork Orange in three weeks, he in fact composed the novel over a period of eighteen months and it’s likely that the plan in this diary/notebook dates from 1960, the year in which Burgess signed a publishing contract for the novel. A second notebook, held at the University of Angers in France, contains further notes by Burgess on the development of nadsat.

For conservation reasons, access to Burgess’s original diary is restricted: please contact our archivist for more information.