The Earthly Powers Bookshelf: Somerset and All the Maughams by Robin Maugham

-

Graham Foster

- 16th October 2020

-

category

- Blog Posts

Anthony Burgess’s Earthly Powers is a book made up of other books. The Earthly Powers Bookshelf charts that literary map, using as its base Burgess’s library at the International Anthony Burgess Foundation.

Anthony Burgess described the protagonist of Earthly Powers as ‘an aging homosexual writer based on William Somerset Maugham’.

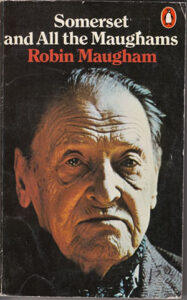

The source of this inspiration is not solely Maugham’s own writing, but the strange biography written by his nephew, Robin, which Burgess read on publication in 1966. Throughout this post, I will refer to ‘Somerset’ and ‘Robin’, to avoid a confusion of Maughams.

Somerset and All the Maughams aims to chart the Maugham family history back to the late 1700s, but it inevitably focusses on ‘Uncle Willie’, the relation with whom Robin spent the most time, who was also the most famous member of the family.

Somerset and All the Maughams aims to chart the Maugham family history back to the late 1700s, but it inevitably focusses on ‘Uncle Willie’, the relation with whom Robin spent the most time, who was also the most famous member of the family.

There are details of Somerset’s biography which Burgess turned into the facts of Toomey’s life: a French mother and an English father; an early career writing for the stage; time spent in Malaya; and his success as a writer of novels and short stories. These details were well known, but what Somerset and All the Maughams brings is a personal view of Somerset, his private attitudes, and his personality. These aspects influenced Burgess in the creation of Toomey more than the mere facts of biography.

Somerset was fiercely private and few details of his life were made public when he was alive. Robin’s book, originally published the year after Somerset died in 1966, revealed that he was gay, and detailed his relationships, particularly with his secretaries, Gerald Haxton and Alan Searle.

Somerset’s later years are of particular interest to the reader of Earthly Powers. Robin describes the scene of his uncle’s final years:

At ninety Willie led a quiet but comfortable life at the Villa Mauresque. He had six servants and four gardeners. He was looked after by Alan Searle, who had been with him constantly since the end of the [1939-1945] war.

When we are first introduced to Toomey, he is in his palatial Mediterranean villa, accompanied by his secretary (or ‘catamite’, as he refers to him in the novel’s famous opening line), Geoffrey. This relationship, and Geoffrey’s character, seems to have been influenced by Somerset’s relationship with Haxton (and, to a lesser extent, Searle).

Geoffrey is described as enthusiastic and bright when Toomey first meets him in California, but he turns out to be volatile and drunken, bad tempered and, it is suggested, a sexual predator whose behaviour has forced Toomey’s relocation from Tangier to Malta. Robin describes Haxton in similar terms:

He was an energetic, pleasing young man when they first met. From the days when he had been a schoolboy he had grown used to being admired. He was already a bit spoilt. He had begun to drink heavily and he became wild and violent in his cups. His reputation was notorious and his behaviour was reckless. In the winter of 1915 when Gerald was in London he was arrested on a charge of gross indecency.

The conversations Somerset had with Robin about his sexuality are reported in the book, and these add something to our understanding of Toomey’s character. Toomey believes that his sexuality is part of his nature, given by God, and there is little he can do to reconcile his desire with the teachings of the Church. Somerset told Robin: ‘There’s no point in trying to change your essential nature […] One hasn’t a hope.’

Despite both Somerset and Toomey voicing similar concerns, they can both be seen to hide their true nature to the outside world. Somerset kept up the pretence of heterosexuality in his writing and in interviews. Toomey also feels that he cannot be open about his sexuality in public.

When he is called upon to defend The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall at its obscenity trial, he declines, stating that he could not admit to being gay ‘in the present state of public opinion.’

When he is called upon to defend The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall at its obscenity trial, he declines, stating that he could not admit to being gay ‘in the present state of public opinion.’

Despite these similarities, Somerset and Toomey diverge in important ways.

Toomey is charming, gregarious and, for the most part, interested in other people. Robin describes Somerset as bitter, tormented by remorse, and deeply misogynistic. He enjoyed accusing both friends and strangers of being poor, feeding visiting writers with hot onion soup, steak and kidney pudding, and chocolate soufflé under the scorching Mediterranean sun, accusing them of not having had ‘a square meal for weeks’. At the same time, he was mean with money, preferring to walk several blocks in a New York snow storm, rather than pay for a taxi.

Toomey cannot share these traits. He has to be an engaging narrator, and he has to be fun. The flashes of sarcasm or bitchiness he displays are not bitter, but conspiratorial and funny. Burgess seems to be aware that Somerset was not well liked by his peers: he was called ‘the lizard of Oz’ by Noel Coward; and Virginia Woolf said ‘he has the look of a dead man’. Burgess was reluctant to give Toomey the same characteristics.

Even so, the insights Burgess drew from Robin Maugham’s unsparing and revelatory biography of his uncle were vital in making Toomey such a richly textured character.

Pictured above: Cover detail from the Europa edition of Earthly Powers.

Throughout 2020, the Burgess Foundation has been celebrating the fortieth anniversary of Earthly Powers, of which this series is a part. Find out more about the Earthly Powers 40 project.