The Earthly Powers Bookshelf: Ulysses by James Joyce

-

Graham Foster

- 23rd October 2020

-

category

- Blog Posts

Anthony Burgess’s Earthly Powers is a book made up of other books. The Earthly Powers Bookshelf charts that literary map, using as its base Burgess’s library at the International Anthony Burgess Foundation.

The novel which exerted the strongest influence on Anthony Burgess’s literary work is undoubtedly Ulysses by James Joyce, which he first read as a schoolboy in the 1930s.

The first novel Burgess completed, A Vision of Battlements (written in 1952), was inspired by Joyce’s use of the structure of a classical myth to illuminate contemporary concerns. Where Joyce used the story of Homer’s Odyssey as the basis for his novel, Burgess drew on Virgil’s Aeneid. Ulysses continued to preoccupy Burgess’s imagination, and in 1965 he published his first critical commentary on Joyce, Here Comes Everybody.

While Ulysses inspired the inventive approach to language in novels such as Nothing Like the Sun and A Clockwork Orange, its influence on Earthly Powers is more straightforward.

While Ulysses inspired the inventive approach to language in novels such as Nothing Like the Sun and A Clockwork Orange, its influence on Earthly Powers is more straightforward.

The fictional world that Kenneth Toomey inhabits contains James Joyce as a fictional character. His novel Ulysses provides the background to a formative episode in Toomey’s life. The young Toomey describes a sexual encounter with the poet George Russell (known as ‘A.E.’) in Dublin on 16 June 1904, the day on which Joyce’s novel is set. Russell also appears as a character in the ‘Scylla and Charybdis’ chapter of Ulysses, in which he discusses Shakespeare with Stephen Dedalus in the National Library. Toomey describes Russell’s appearance in Ulysses an ‘eternal and unbreakable alibi’ for the sexual act he is said to have committed with Toomey in the Dolphin Hotel.

In using Ulysses as the basis for this episode, Burgess may be revealing his own view of Joyce’s novel as a formative work which was instrumental to him in becoming a writer.

Joyce is Burgess’s literary forebear, but Toomey’s relationship with him is more complicated: Joyce’s literature finds its way into his life, but he does not value it much. Toomey’s encounter with George Russell is a character-building moment, and it triggers a lifelong distrust of men who would exploit the young for sexual gratification. Speaking of Joyce’s book, Toomey writes:

I have never been able to take the book seriously, as I told [Joyce] myself in Paris. All the inner broodings and exterior acts of the work seem so innocent.

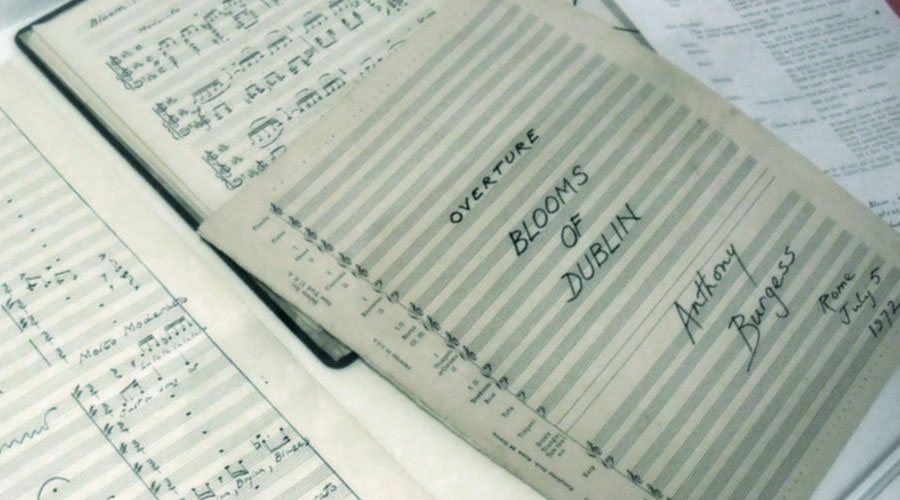

Ulysses reappears towards the end of Earthly Powers, in the guise of a musical written collaboratively by Toomey and Domenico Campanati. The Blooms of Dublin, performed on stage in the novel at some time before 1963, recasts the novel as a music-hall work, in which, we are told, ‘Haines, the Englishman, went round with a gun and the intention of killing Stephen Dedalus, whom he identified with the black panther of his dreams.’

Toomey voices some reservations about this action being ‘coldly injected’ — but, in a self-referential flourish, he praises the songs of the musical. The songs which appear in Earthly Powers were part of a musical project that Burgess himself had completed in 1971, though it did not appear in its finished form until 1982, the centenary year of Joyce’s birth.

In a review of the radio production of Blooms of Dublin for the James Joyce Broadsheet, ‘Stephen Green’ (surely a pseudonym, punning on St Stephen’s Green in Dublin) writes about the unlikely endeavour of adapting Ulysses as a stage musical:

Somewhere around the seventieth or eightieth chapter [actually chapter 73] of Anthony Burgess’s meganovel Earthly Powers, the precarious hold on the Aristotelian notion of probability, that has brought us through the astonishing, high-brow, Kilroy-was-here epic up to this point, breaks down completely and we hear that a character is to sing a part in a musical version of Joyce’s Ulysses called Blooms of Dublin.

No-one could possibly have the knowledge, the boundless ambition, or the questionable taste to produce such a work in real life, we protest. Even in a novel it would have to be done with the novelist’s tongue stuck firmly in his cheek.

For Joyce scholars and fans of his work, adapting Ulysses seemed to be an impossible feat. Burgess hints at this attitude in Earthly Powers. Yet, Burgess believed (in an echo of the central thesis of Here Comes Everybody) that Ulysses was not a novel for academics to pore over, but a novel for everyman and everywoman: ‘I attempted to celebrate Joyce’s centenary by suggesting — through a musical adaptation in a popular mode — that Joyce had something to say to ordinary people, not just the professor.’

The fictional James Joyce in Earthly Powers seems to be quite envious of Toomey’s popular success:

He had not read me but he had heard doubtless that I was a mere popular novelist and not to be feared as a literary rival. I think he rather admired me for having made money out of a trade which he himself could pursue only with lavish subventions.

Although a radio version of Burgess’s Joyce musical was performed in 1982, he had always intended it for the stage. Burgess wrote about the reception of this radio performance in 1986, highlighting the conflict between Joyce as a novelist for ordinary readers and his status among scholars: ‘Literary critics trounced me for daring to tamper with one of the great novels of the century, making mere entertainment out of a complex verbal artefact whose appeal is highly rarefied.’

Although a radio version of Burgess’s Joyce musical was performed in 1982, he had always intended it for the stage. Burgess wrote about the reception of this radio performance in 1986, highlighting the conflict between Joyce as a novelist for ordinary readers and his status among scholars: ‘Literary critics trounced me for daring to tamper with one of the great novels of the century, making mere entertainment out of a complex verbal artefact whose appeal is highly rarefied.’

Domenico’s musical in Earthly Powers provokes a similar reaction when it is performed. A Joycean academic in the audience claims that he never thought ‘they’d make a public entertainment out of it […] They’ll be doing The Magic Mountain next.’ Toomey defends his right to adapt literature, claiming that the musical recalls ‘the good Paris days of the avant garde, youth and hope.’

The role of Ulysses in Earthly Powers is complicated by Toomey’s lack of respect for the novel. Towards the end of his life, Burgess also revealed reservations about Ulysses. In a lecture he gave at the Princess Grace Irish Library in Monaco in 1990, he claimed that the experiments of Ulysses had led to a creative cul-de-sac:

Ulysses raised and solved new fictional problems which had no general application: what Joyce discovered he discovered for himself only. To write novels after Ulysses meant ignoring everything in that work except a new attention to dialogue and récit.

But Burgess could not completely ignore Ulysses. The two scenes in Earthly Powers influenced by Joyce book-end the novel, and both attempt to place Joyce’s novel at the centre of lived experience and entertainment.

Despite Toomey’s seeming indifference towards Joyce’s work, Burgess could escape its pull, and in using Ulysses as part of the scaffolding of Earthly Powers, he underlined its importance to his own development as a writer.

Pictured above: Blooms of Dublin score held at the Burgess Foundation.

Throughout 2020, the Burgess Foundation is celebrating the fortieth anniversary of Earthly Powers, of which this series is a part. Find out more about the Earthly Powers 40 project.