The Earthly Powers manuscript

-

Burgess Foundation

- 1st July 2012

-

category

- Blog Posts

The Burgess Foundation has a complete electronic copy of the typescript of Earthly Powers. The typescript itself was found in 2012 in the files of Gabriele Pantucci, one of the literary agents who represented Burgess in his lifetime. It is unclear why the typescript was not returned to the author after publication, which would have been the normal practice for an agent, but we are grateful to Mr Pantucci for allowing the Foundation to inspect it. Before restoring the typescript into his hands, we made a high-resolution scan, which is available for consultation by researchers.

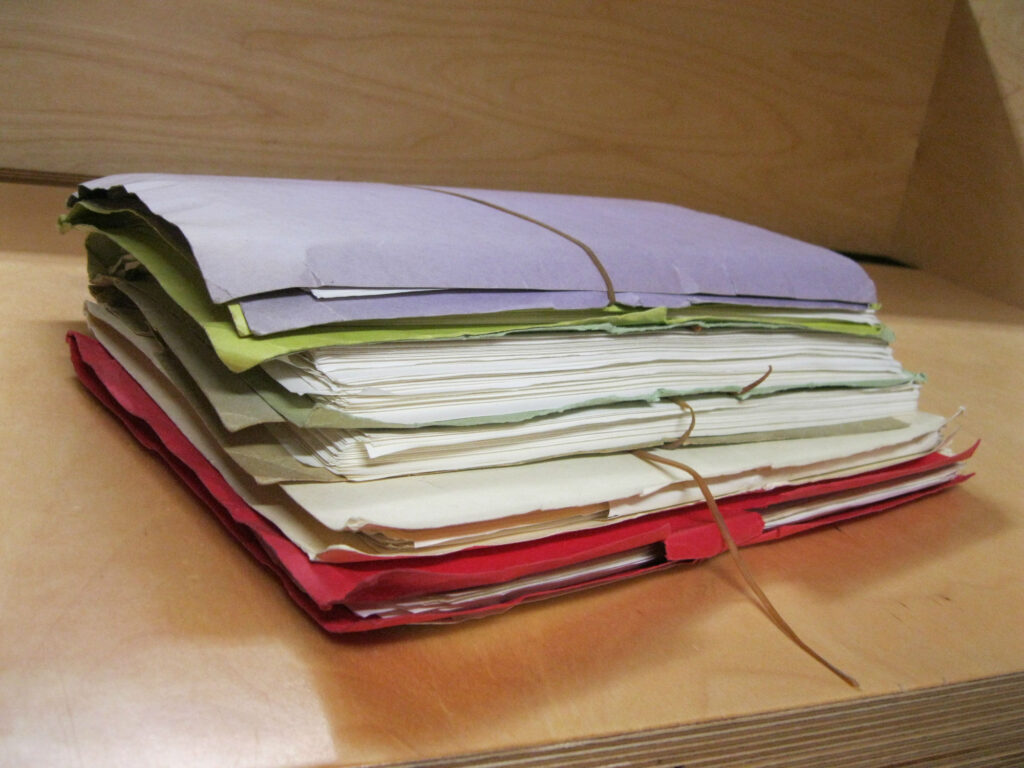

When we opened the large envelope which had held the typescript for more than 30 years, we discovered six coloured folders, each of which contained approximately 100 pages of typescript.

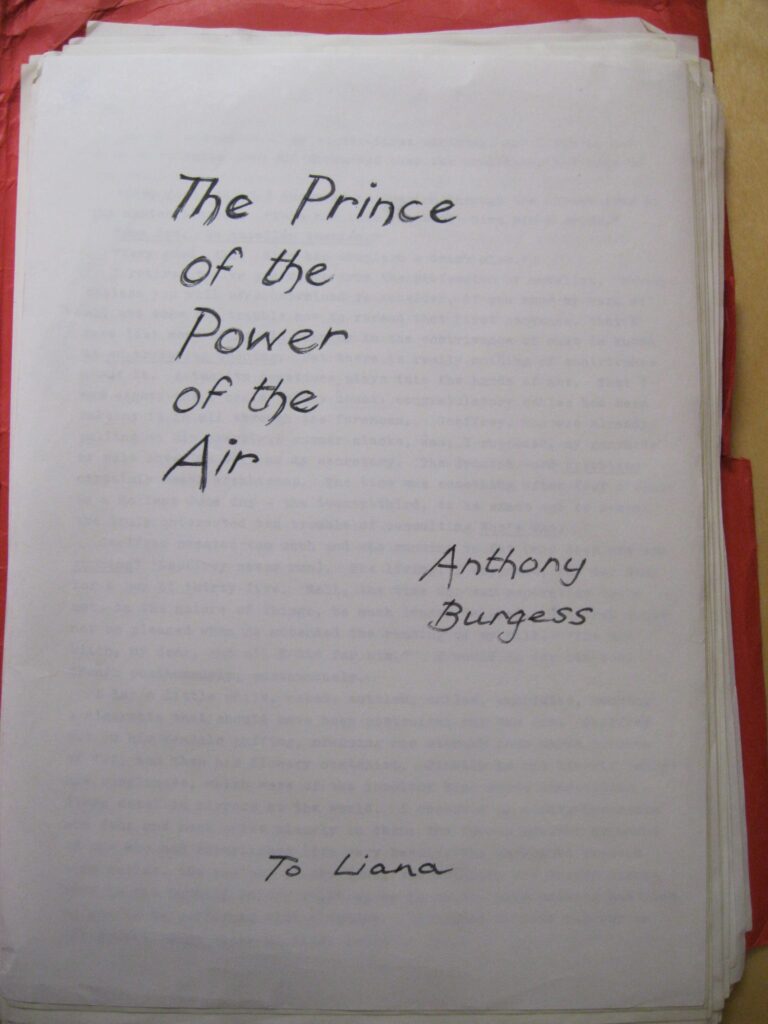

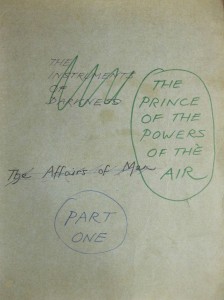

A preliminary survey of this material has revealed a good deal of new information about the book, particularly relating to the genesis of its title. Burgess’s original title for his novel — about a fictional pope and a novelist resembling Somerset Maugham — seems to have been ‘The Affairs of Men’. This was then changed to ‘The Instruments of Darkness’, a quotation from Shakespeare’s Macbeth. After that, he decided to call it ‘The Prince of the Powers of the Air’ — a misremembered line from the Bible (actually a reference to the devil in the Epistle to the Ephesians, 2:2) — which, presumably after he’d checked it, was later corrected to ‘The Prince of the Power of the Air’.

It is clear from this finished typescript that, at the point when Burgess completed the novel and delivered it to his editors, it was still known as ‘The Prince of the Power of the Air’. By the time the publishing contracts were drawn up, the book was being referred to as ‘Infinite Power’ and ‘Ultimate Power’.

The decision to publish under the title Earthly Powers was reached only a few weeks before publication in October 1980, on the advice of Michael Korda, Burgess’s New York editor at Simon and Schuster. In French, the book is known as Les Puissances des Ténèbres (The Powers of Shadows); in German, Der Fürst der Phantome (The Prince of Phantoms); in Italian, Gli Strumenti delle Tenebre (The Instruments of Darkness); and in Swedish, Jordiska Makter (Underground Powers).

One other discovery from the typescript is that the name of the main character has been altered (in Burgess’s handwriting) to Kenneth Marchal Toomey at a very late stage of composition. In earlier drafts he was known as Kenneth Markham Toomey, a name which is much closer to Maugham — with whose life Toomey shares a number of characteristics, including his high reputation as a playwright and his interest in colonial Malaya.

It is possible that Burgess changed this name because he did not want readers to make the too-easy identification between Toomey and Maugham. Perhaps he was also worried about offending his friend and fellow novelist Robin Maugham, the less famous nephew of Somerset Maugham, who Burgess had met and befriended when he visited Tangier in November 1963. Robin Maugham was still alive when Earthly Powers was published in 1980. He died the following year, aged 64.

We do know that Burgess was fascinated by Somerset Maugham and his prolific writing career. Burgess wrote Maugham’s obituary for the Listener in 1965, and he prepared an edition of Maugham’s Malaysian Stories for publication by Heinemann Asia in 1969. His private library contains numerous copies of novels, plays and short stories by Maugham, as well as the biographies and memoirs by Robin Maugham, Frederic Raphael, Ted Morgan and Robert Calder.

When Burgess was asked about the mother he never knew by Anthony Clare, in a BBC radio interview in 1988, he replied that he remembered nothing about her, but he imagined that she probably resembled the barmaid Rosie Driffield in Somerset Maugham’s novel, Cakes and Ale. There is no doubt that some of this affection for Maugham spills over onto the pages of Earthly Powers.