‘The true literary experience’: Anthony Burgess and Martin Bell

-

Matthew Whittle

- 27th May 2014

-

category

- Blog Posts

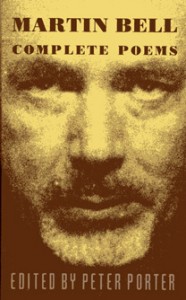

In You’ve Had Your Time (1990), Anthony Burgess describes his move to Chiswick in 1964 and his desire ‘to meet writers to whom, as for me, writing was an agony mitigated by drink’. Chief among his new ‘literary confreres’ was the poet and translator Martin Bell, who is described as ‘shabby, bad-toothed’ and ‘doomed to die of drink and be posthumouslessly neglected’.

In the late-1950s, Bell was a prominent member of The Group, a London-based collective formed by Philip Hobsbaum that had disbanded by the mid-1960s. During Burgess’s time in Chiswick he and Bell became close friends, sharing a love of reciting poetry over double gins. ‘The digging out from memory of lines from Volpone or The Vanity of Human Wishes with the twelfth glass,’ writes Burgess, ‘is the true literary experience’.

Burgess and Bell’s friendship developed at a time when the figure of the poet was becoming increasingly central to Burgess’s writing. Following Everett in The Right to an Answer (1960) and Redvers Glass in One Hand Clapping (1961), Burgess invented Francis Xavier Enderby, the poor and unanthologised protagonist of the Enderby quartet (1963-1984). Enderby embodies Burgess’s view of the quintessential poet figure: solitary, serving his Muse above all else, and resisting external forces pressing him to become a ‘useful citizen’.

Bell was clearly an admirer of Burgess’s creation. In a 1973 letter to The Listener addressing Phillip Larkin’s omissions from The Oxford Book of Twentieth-Century English Verse, Bell asks provocatively, ‘Where is F.X. Enderby?’ Arguably, Bell’s poem ‘A Vocation Possibly’ is influenced by the character of Enderby, depicting as it does the poet in his ‘monk’s cell / Pantaloon decrepit scholar’s den’, surrounded by books that ‘refuse decorum’ and typing while listening to ‘Ludwig Van’.

As well as meeting to drink and recite poetry, Burgess composed a musical score for Bell’s poem ‘Sinilio’s Broadcast Script’, which accompanies an apocalyptic announcement, and in his Collected Poems Bell dedicates ‘Pets’ to Burgess and his first wife Lynne. Aiding him professionally, Burgess also had Bell take over from him as opera critic for Queen magazine in 1965. Bell’s fellow Group poet Peter Porter maintains that ‘his hand lay behind some of Burgess’s own judgements, especially of Stravinsky and Britten’. Their regular meetings came to an end, however, when Bell was appointed as a Gregory Fellow at the University of Leeds in 1967. It was a move that Bell came to resent, writing in his sequence The City of Dreadful Something of the ‘perpetual winter here in Leeds’ where people ‘talk about football all year round’. ‘Leeds is hell’, the sequence concludes, dominated by ‘the new brute building called Polytechnic’ and the ‘Merrion Centre with its special subways for mugging’.

Despite Bell’s move, he and Burgess remained in contact, as is documented by a number of letters held in the Burgess Foundation collections. In one exchange in 1976, the poet requests Burgess’s help in making a ‘literary comeback’. He confides in a rather confessional ten-page letter that ‘the Muse has taken to deserting me for longer periods, but not entirely’. Burgess replied with the playful riposte, ‘You poets are lazy buggers but more honoured than us novelists,’ and offers to make an introduction between Bell and an American literary agent.

Despite looking ahead to what he calls his ‘Late Great Period’, Bell passed away in 1978. When Burgess is informed of Bell’s death by his girlfriend Christine McCausland, he writes from Monaco lamenting that ‘local papers don’t concern themselves with the deaths of British poets – even important ones’ and offers to compose a short ‘in memoriam piece for piano’ as ‘my tribute to his genius… and also to his and my common loves’. As well as opera, double gins and the performance of great verse, their common loves included the increasingly neglected figure of the poet, who was responsible – in the Eliotic sense – for purifying the language of the tribe.

This research forms part of an ongoing project funded by the Leeds Humanities Research Institute (LHRI) at the University of Leeds.