Twanging Nonsense: Burgess on Pop Music

-

Graham Foster

- 20th March 2013

-

category

- Blog Posts

Anthony Burgess’s reputation as a composer and musician has now been re-evaluated and bolstered with several recent public performances of his work. He was brought up around music, as his parents were performers in the music halls in Glasgow and Manchester. Burgess’s 1986 novel, The Pianoplayers, draws on the experiences of his father who left the music halls to play piano in pubs and to accompany silent films.

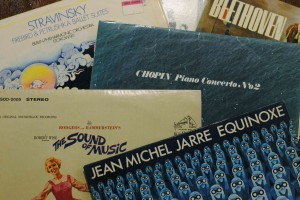

Burgess’s own musical influences were resolutely classical. Canonical composers such as Beethoven, Mozart, Chopin and Stravinsky dominate the large record collection at the International Anthony Burgess Foundation. There are a few anomalies though, with records by artist such as the Beatles, Fleetwood Mac and Booker T. & the M.G.’s. These are oddities in Burgess’s collection because, throughout his life, he was vocal about his dislike of popular music.

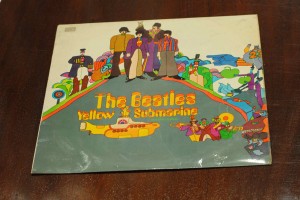

In 1968, Burgess published the second Enderby novel, Enderby Outside. In it, the eponymous poet meets the front man of a band called Yod Crewsy and the Fixers. Yod Crewsy, a literary rendering of John Lennon, is a plagiarist, egoist and all-round toerag who fakes his own assassination as a publicity stunt. Burgess’s loathing of the Beatles is well-documented, making the record collection’s anomalous LP copy of Yellow Submarine rather mysterious (could he have softened towards them by 1969? Have Paolo Andrea’s records been mixed up with his father’s? Could it have been because the actor who voiced John Lennon in the film also appeared in Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange?). ‘I despise whatever is obviously ephemeral and yet is shown as possessing some kind of ultimate value,’ he said in 1973. ‘The Beatles, for instance. Most youth culture, especially music, is based on so little knowledge of tradition, and it often elevates ignorance into a virtue’. Writing in You’ve Had Your Time, Burgess remembers the ‘madness of adulation’ that the Beatles inspired, seeing their music as ‘tied up with youth, the miniskirt, easy sex’. The Beatles would pose a threat to The Bawdy Bard, Burgess’s proposed musical about the life of Shakespeare. The Hollywood producers wanted the Beatles to write the songs, but Burgess ‘feared their idiom’, opting instead to write his own musical accompaniment. The film was never made.

By 1980, Burgess’s opinion of the Fab Four had softened slightly. Speaking to Kenyon College Radio, he says, ‘There was a specific kind of youth culture that was of some importance. We got some art out of it; we had the Beatles who were quite a large phenomenon. They were taken seriously not only by youth but also by adults, and erudite music professors would give talks about the structure of Eleanor Rigby or spend hours on radio dissecting the record called Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club’. He goes on to say, on the subject of new musical compositions, ‘We are really in a bad way, and probably rock may be a salvation because at least you know what it is. It’s a style, it’s a form. I would say thank God for rock, because at least it is a tradition which is fruitful, and goes on producing new forms that are intelligible to a large, universal group’.

One rock group Burgess had a run-in with was the Rolling Stones. In the mid-Sixties, the band was instrumental in an attempt to adapt A Clockwork Orange for film, with Mick Jagger to lend Alex his signature strut. ‘I admired the intelligence, if not the art of this young man,’ Burgess writes, ‘and considered that he looked the quintessence of delinquency’. Jagger’s involvement with the film is commemorated very briefly in Kubrick’s version: in the record store scene, Alex walks past a poster for the movie Ned Kelly, a role Jagger did actually play.

Burgess’s scorn for pop music was nothing compared to his loathing of the people who he believed foisted it on the unsuspecting public: the disc jockeys. ‘They corrupt the young,’ he wrote in 1967, ‘persuading them that the mature world, which produced Beethoven and Schweitzer, sets an even higher value on the transient anodynes of youth than does youth itself. For this, they stink to heaven’. This scorn did not wane. In You’ve Had Your Time, Burgess writes about a specific disc jockey who ‘had been noted for bipartite hair-dyes and his love of the young’ and ‘boasted of the “quids” he had earned in his promotion of musical garbage’. This man was a villain in Burgess’s eyes long before the rest of us cottoned on.

Yet, Burgess’s loathing of the pop music form shouldn’t be seen as regressive grumbling. The record collection at the Burgess Foundation, while dominated by classical music, has an eclectic mix of artists. Chopin sits next to Count Basie and Oscar Peterson, The Sound of Music soundtrack accompanies recordings of Gregorian Chanting, and Jean Michel Jarre is seen throughout. Pop, for him, was a narrow form, indicative of the naivety of youth, and incapable of the sophistication he hoped for in his own artistic work.