Volunteering at the Burgess Foundation, Evelyn Ashmore

For about half a year I have been working with my fellow volunteer Kayleigh to explore the collection of artworks at the Burgess Foundation. If you are familiar with the Foundation’s archive, you will know that many areas within it remain uncatalogued. This remote project has helped the archive to chip away at cataloguing, and as a result there is now much better documentation of the art collection, which will be of value to future researchers.

I graduated with an undergraduate degree in History in 2021 and was certain that I wanted to venture into the archives and heritage workforce, but I needed experience. Due to the pandemic, I was unable to obtain this during my degree. I sent out some rather desperate emails to museums, repositories and even business-based archives. After so many failed attempts to gain the knowledge I needed to progress, Anna Edwards, the Burgess Foundation’s archivist, contacted me last summer with information about this new remote role. It was perfect.

However, I didn’t know anything more than the words ‘A Clockwork Orange’ when it came to Anthony Burgess. This didn’t prove to be a problem, and I’ve learnt so much as I’ve progressed through the project without needing to read any Burgess. This understanding has come solely from engaging with such a rich and personal collection.

My favourite aspect of the project has been working with a variety of material culture and therefore getting an insight into how different mediums of artwork are cared for in an archive. My past experience had been with books, so coming across things like pressed flowers when filling out the catalogue was something completely unexpected.

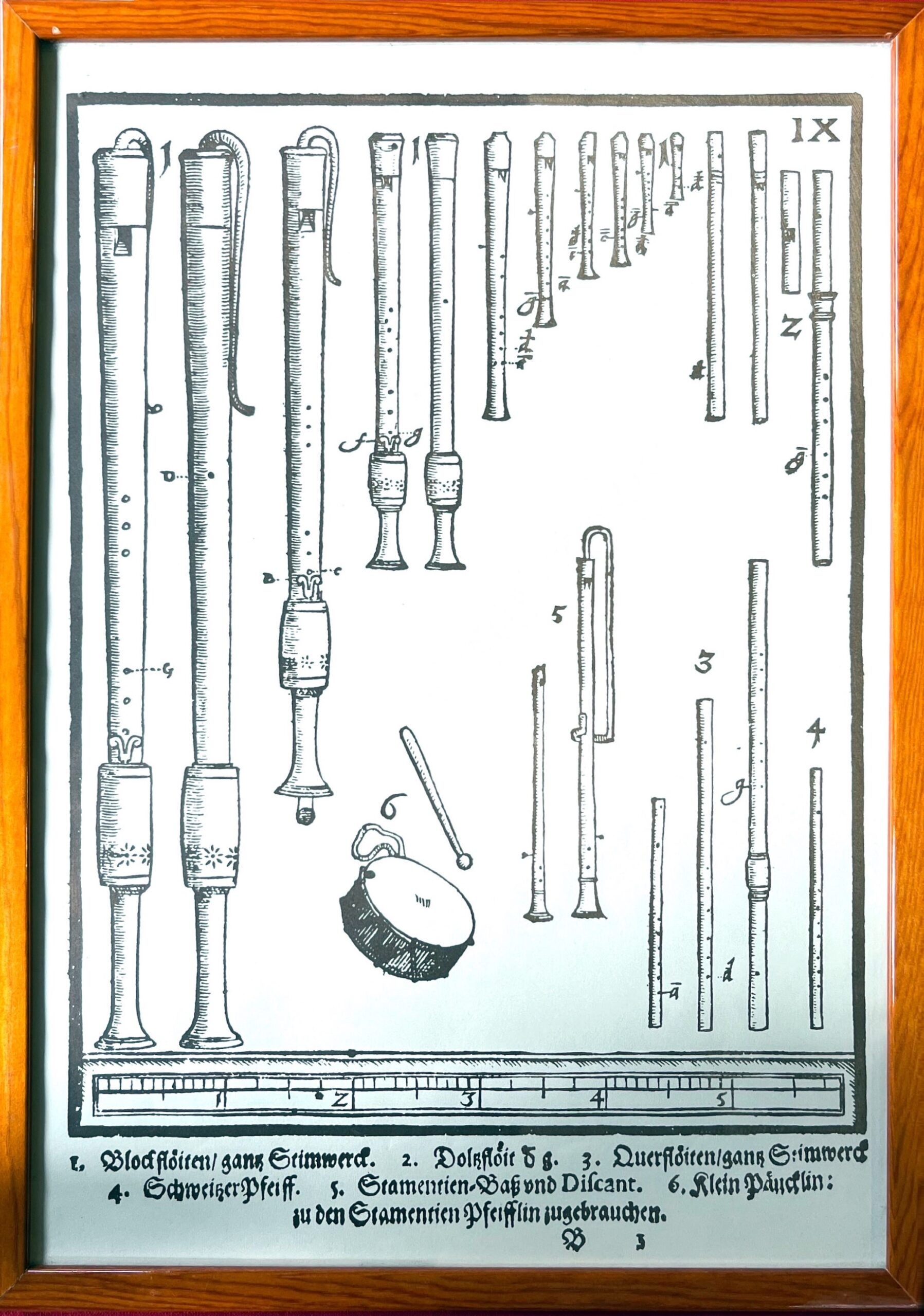

Recently I got to visit the archive in person to view the collection and see some of the pieces I’ve been cataloguing. It put into perspective once again how unique the collection is. Viewing other items in the archive, I was able to make links to the artwork I’d been working with and create a more comprehensive picture of Burgess’s life. For example, I got to see Burgess’s musical instruments, which I linked to copies of seventeenth-century prints he owned of the medieval Sourden woodwind family (below).

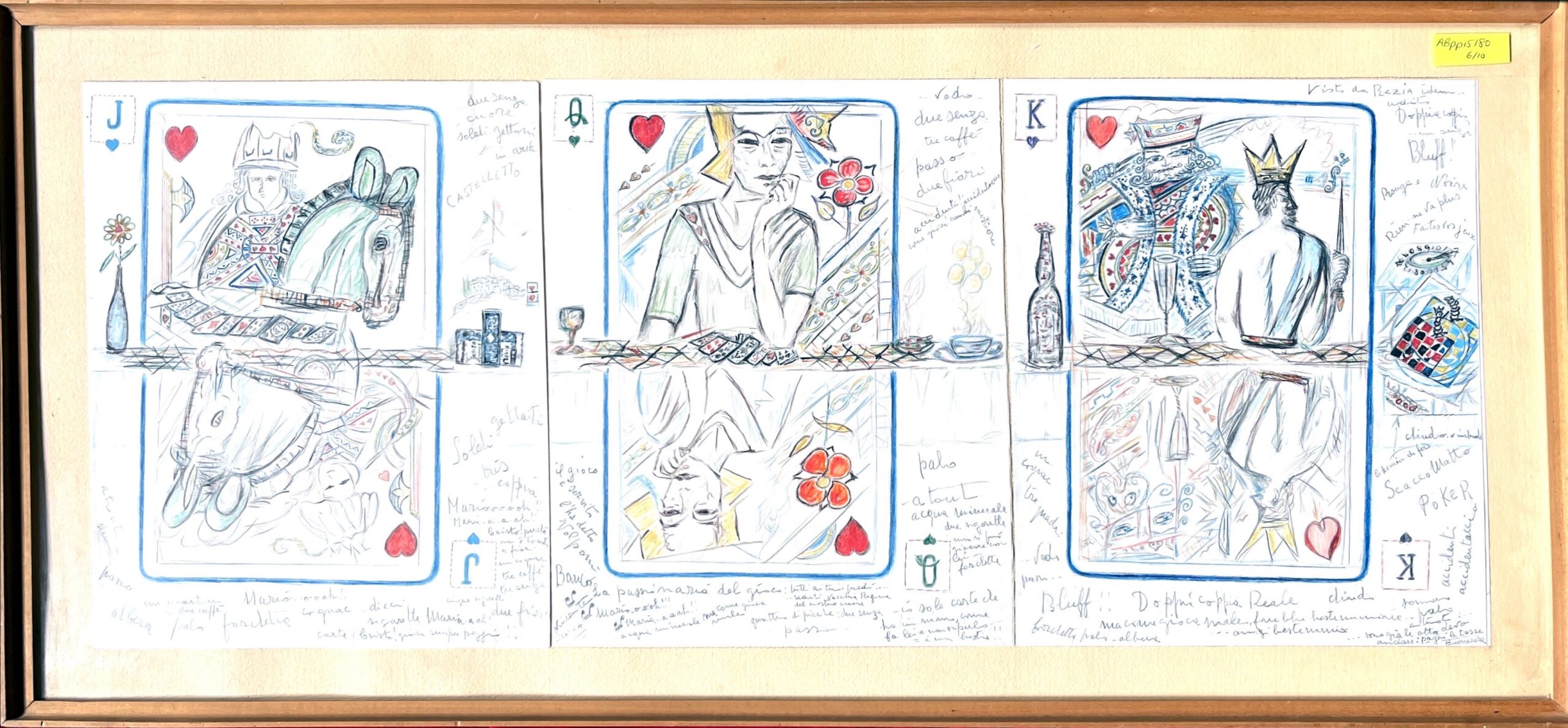

The works I’ve loved most, though, have to be the extensive collection of vibrant and bizarre watercolour images drawn by Burgess’s mother-in-law, Maria Lucrezia Macellari. They are abstract and amateur in nature, but captivating as the interpretations of her drawings are endless. Some common features of her work include eyes and religious symbolism. The fact that there is no written explanation of her drawings is fascinating, and an entire project could be created from this cluster of pictures. Surprisingly, while learning about Burgess, I’ve simultaneously been studying his relatives. Again, this highlights the personal and intimate nature of the archive and I think that gives the Foundation a special feeling, because of the connections you can form with the collection in many different ways.

I’ve loved working with the Foundation and I hope this project is just the beginning. The sheer amount of work that needs to be done to better categorise the archive is humongous. Based on the artwork project, this work will be rewarding due to the abundance of information it holds on Burgess and his works, family and life, but also because the collection is so diverse materially. I can only begin to imagine the opportunities that will crop up as more work is done in the archive and it becomes accessible to a wider range of users.