Burgess Memories: Bruce Parks

-

Bruce Parks

- 17th October 2017

-

category

- Burgess Memories

He wasn’t exactly what we expected. No, my brothers. He was not like Alex, nor even like one of his three droogs.

‘Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a mirror and a razor lay crossed,’ he began reading to us.

Flashbulbs popped. The New York Times. Newsweek. Reporters, photographers in the classroom, filling the first row, between us and him. Say something and you might be quoted. I was. (‘I don’t know how he could write like that and be like that,’ or something equally vague.) In any case, it was clear this wasn’t going to be your typical English class.

Burgess had accepted the position of Distinguished Professor of English at the City College of the City University of New York (CCNY). This was 1972, just a year or so after the film version of A Clockwork Orange had been released and propelled to the top of our counter cultural icons, right up there, in our minds, with the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. I was then an aspiring filmmaker, but after I read A Clockwork Orange, I wasn’t so sure. The book, I told the examining board of the new CCNY school of film studies, to which I was applying for admission, was better than the film. What? They hadn’t heard me right. Book better than film? The book could do things more than the film, I think I said. Like the violence, which seemed to me more artfully described in the book than it was depicted in the film. I was doomed, of course, rejected by the examining board. I decided to try writing and signed up for the Burgess class. So here I was amongst a small group of students in Professor Burgess’s class on James Joyce in the fall of 1972.

His plan for the class was to read out loud to us Ulysses in its entirety, chapter by chapter, with his commentary interspersed. Our job was to read a chapter ahead and get us much out of each chapter as we could. Then just listen. He brought it all alive. A one-man show, with a variety of voices, voices we also would get to know if we were lucky enough to catch his occasional afternoon readings from Enderby or Nothing Like the Sun in the City College library.

Had we really expected Alex? Perhaps not. The papers wrote much about Burgess that preceding summer. The ‘rip-off,’ they quoted him as saying, was the central motif of the times. We had read about the mugging of his wife, his near miss with death, his late start at writing, his first love of composing. So we knew a little about him, but very little. Not many had read anything by him, except perhaps A Clockwork Orange.

The reporters and photographers had left and now it was just us. A small class of perhaps fifteen New York City kids, all fairly typical looking, one with a yarmulke. City kids who took the subway to school and hiked through the streets of Harlem to get to class.

He stood before us holding the text of Ulysses, the thick black book precariously balanced on the lectern of his left hand, while with the fingers of his other hand he repeatedly stroked his hair back into position, so that the long length was swept across and over his bald spot. He read rapidly, his jaw undulating, propelling out mouthful after mouthful of sound, musical text, modulated vowels, diphthongs, and consonants, read with the agility of an impresario performing a recital or a piano player in a saloon.

My copy of that ‘chaffering allincluding most farraginous chronicle’ is marked with notes taken during that class, as he guided us through, marking the route like signposts.

By the end of the semester, most of us had not only read Ulysses with Burgess, but also Dubliners and A Portrait of an Artist. We had come into his world philistines perhaps, and left at least somewhat enriched. The one young man with the yarmulke, the Talmudist, had taken off his yarmulke, now prepared to venture beyond the realms of his strict upbringing to explore new horizons.

There was a second class, in the spring semester, on Shakespeare which was held in a large lecture hall usually reserved for film classes. It started at eight, which was too early for college students, especially those making an hour or more commute into the city to get to class. The result was unfortunate. Burgess mainly lectured to sleepy students. At one point, frustrated with the lack of response, he asked: ‘Any questions? Any questions at all on anything?’ No one said a word.

At this time Burgess was having trouble with U.S. Immigration, and I remember mentioning to him that John Lennon was also finding it difficult to stay in the country. Burgess was empathetic. John Lennon, not a bad man, he said. A consolation the former Beatle may have found comforting, considering the harsh treatment Burgess gave the band in Enderby.

We knew he would sometimes get off the IRT train a stop or two early and walk through the streets of Harlem to the college. He carried with him a walking stick which actually was a sword stick, having concealed within it two lethal large knives. When he showed it to me, pulling it apart in one violent movement, I glimpsed Alex in him then. However, one day he didn’t arrive at class. Had he been mugged? No, it turned out he had a bout of his recurring malaria, which he had picked up many years earlier (in Malaya perhaps?). By the next class he was fine.

I had also signed up for his creative writing class, which was held in the evenings in his apartment on 93rd Street. We sat in the living room around the coffee table, freshly provisioned for each class with large bottles of red and white wine. Often his wife Liana was occupied with the phone in the kitchen, speaking in Italian, dealing with the competing forces of the literary and film worlds, the publicists, the agents, the producers, the artists, the friends, while we sat in the calm of it all, in the eye of the hurricane, reading out loud our fledging work, whilst Burgess smoked his small black cigars.

The students in the writing class were an eclectic mix. There was a young poet, Lydia, and another woman working, I believe, on a novel. There was an Irishman who was writing a thousand page tome (‘Put everything into it,’ Burgess advised). Two of the students may not actually have been students at the college. One was an exquisite, beautiful young woman, some kind of heiress, with lots of money, old money, and full of manners, grace being alien to us New York kids. She was driven to the class by limousine and picked up afterwards. She was writing a romance novel, for adolescents. She dressed alluringly, and moved around the room like Salome dancing for King Herod. She always sat near Burgess, who said to her once, after a particularly close encounter, ‘I love my wife very much.’ Then he said it again. ‘I love my wife very much.’ I wasn’t sure whether he repeated it to make certain she had heard him, or whether he was reciting it to convince himself.

In general, I often wondered whether Burgess was right to encourage us in our endeavours to be writers. Somerset Maugham in ‘Summing Up’ warned young writers not to devote themselves to an art for which they only had a youthful exuberance. Burgess seemed to have no cautions in this regard and always encouraged us, always found something good in our work to point out. Sometimes he would read a student’s work out loud himself, adding to it a new dimension brought by his dramatic voicing and diction, and it made everyone’s writing sound pretty good. Were we at risk of throwing our lives away for a dream we never would have the talent to achieve? I think Burgess considered this, and he concluded that we would be better people for the pursuit, even if we didn’t succeed, than we would be if he were to discourage us.

Burgess extolled the benefits of studying other languages, especially of reading authors in their original tongues. Starting in the spring semester of 1973 I took courses in Latin, which led me to reading Catullus, Ovid, Seneca, Virgil, and Horace, among many others, in Latin. I followed this a few years later with courses in classical Greek, and read a good deal of Homer’s Odyssey in the original Greek. A new world had opened up for me. When, at the end of the spring semester it was time for AB to go, I handed him a note of thanks:

Tibi gratias ago.

Tibi gratias ago.

Tibi gratias ago.

Burgess actually mentioned this note in an article he wrote shortly upon leaving New York, saying that it was a sort of gift to him, and adding: ‘Et tu Brutus.’

In You’ve Had Your Time, he also mentioned it, shortening my note to ‘Gratias ago. J. Breslow.’

Bruce Parks studied English at City College New York between 1968 and 1972. He is currently based in Boston, where he is responsible for managing engineering activities in the commercial aviation industry.

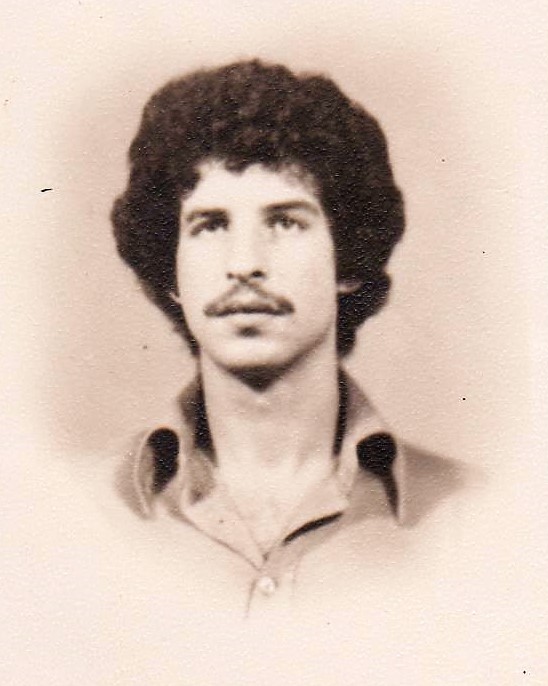

Top picture is courtesy of Bruce Parks and shows him in 1973.