Burgess Memories: D.J. Enright

-

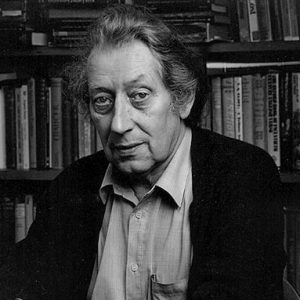

D.J. Enright

- 12th May 2017

-

category

- Burgess Memories

For me the beginning and the end of Burgess’s opus are represented by The Malayan Trilogy and Earthly Powers. Last things were one of his first and enduring concerns, though he never stinted on what went before.

His first three novels, which comprise The Malayan Trilogy, are a hot, spicy curry; the ingredients include realism, riotous fantasy, linguistic comedy often straddling languages, joyous discoveries and deceit and suffering.

Crabbe in The Malayan Trilogy is keen to teach the Malays what the West can do for them; he loses his footing and drowns in a river.

There was in Burgess not so much a sadistic urge to punish his most likeable characters, as a masochistic need to punish himself. Something of Graham Greene there, perhaps, if less relaxedly theological. His people know what is right and good, they have an idea of God, even, but they do what is wrong, and they feel a revulsion against the God who permits wrongs far more terrible than any they have committed.

We talk of word-play, but in Burgess’s case the word ‘play’ is often off the mark, in that his paronomasia is deadly serious as well as deeply searching. His gifts, dangerous ones, temperamental as well as literary, might have made him a poet, but in addition he was possessed by the novelist’s drive to tell a story, to clothe his fierce preoccupations in the flesh and blood of his characters. The Malayan Trilogy recounts a number of parallel or linked stories. Earthly Powers is, if anything, too densely plotted and uncomfortably overpopulated. I wrote at the time that the book ‘carries greater intellectual substance, more force and grim humour, more knowledge, than ten average novels.’

Possibly Burgess lacked that splinter of ice in the heart which keeps the novelist cool and relatively collected, and better able to select and know when to call a halt.

The narrator of Earthly Powers, himself a novelist asks: ‘What is the point of the dialectic of fiction of drama, unless the evil is as cogent as the good?’ But there was never any chance of the good overpowering the evil. In Burgess’s work, you sense a writer pushing himself, not merely his fictional people, towards destruction, as if to test what final damnation is really like.

D.J. Enright was an academic, novelist, poet and critic. He wrote the novel Academic Year (1955) as well as numerous collections of poetry, criticism, and autobiography. He died in 2002. This piece was originally published in The Guardian on 25 November 1993. It is used with kind permission from the Estate of D.J. Enright.