James Joyce in Earthly Powers

Anthony Burgess Earthly Powers is full of literary figures, with perhaps the most notable cameo being James Joyce. On Bloomsday, we examine this most famous novelist inside a novel.

Earthly Powers is full of fictional representations of writers.

The protagonist Kenneth Toomey takes up with invented poets (Val Wrigley, Roger Pembroke), discovers the novels of invented titans of European literature (Jakob Strehler, to whom Burgess awards the Nobel Prize for 1935 — a year in which no prize was awarded), and is himself a highly successful but artistically undistinguished novelist, playwright and lyricist, modelled in part on the real writer W. Somerset Maugham.

And many other real writers also populate the novel, with walk-on parts for Ford Madox Ford, who critiques Toomey’s own writing; Ezra Pound, seen dancing with Sylvia Beach and Adrienne Monnier at a party; and Ernest Hemingway, who shadowboxes in lieu of conversation and drinks heavily.

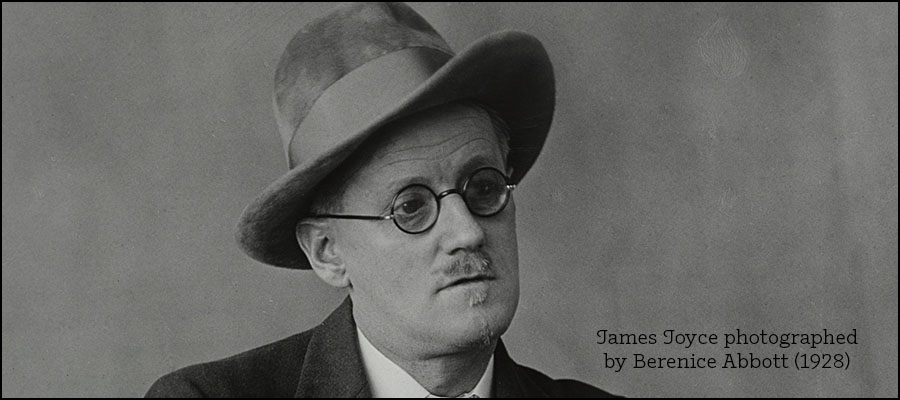

James Joyce also appears as a character, the only time he does so in any of Burgess’s novels. Joyce is a figure who looms behind much of Burgess’s writing. Early experiences of reading books by Joyce as a schoolboy were so profound that they shaped Burgess’s later creative work in fundamental ways, and his engagement with Joyce and his works became the main artistic challenge of his life.

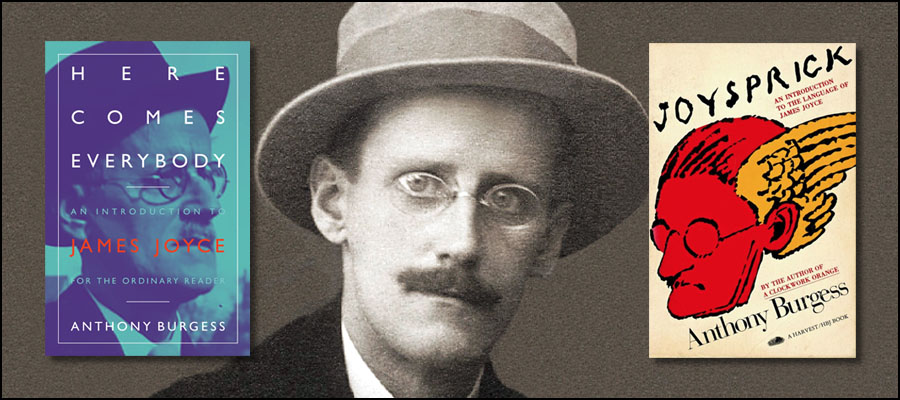

Burgess wrote two full-length critical books on Joyce, Here Comes Everybody and Joysprick; edited A Shorter Finnegans Wake; made at least three television programmes about Joyce; wrote a stage musical adaptation of Ulysses, Blooms of Dublin; and wrote dozens of newspaper articles on his life and work.

Burgess was however sometimes ambivalent about the monitory presence of Joyce’s great novels in the canon, as their shadow lowered over his own attempts. Writing in 1990 (‘Joyce as Novelist’, published in The Ink Trade), he is almost despondent: ‘when I start a new novel to earn my bread, the horrible example of Ulysses glooms from the shelf’. Ulysses is such an awful presence for Burgess because for him it is a work that transcends the novel itself. The scale and ambition of the experimentation with language and form in Joyce is such that it renders subsequent attempts to write novels simply pathetic.

James Joyce’s cameo appearance in Earthly Powers is similarly ambivalent. Very drunk already, he is drinking outside the Bal Guizot bar in Paris when Toomey encounters him. His poor vision, thick speech and almost catatonic state is contrasted with that of his acerbic drinking companion Wyndham Lewis, ‘sober and got up to look like an anarchist, though he resembled rather an undertaker.’ Wyndham Lewis’s writing is described by Toomey as ‘all solid bodies that could only be moved with a crane’, whereas Joyce is ‘all wordflow’.

‘I felt a certain contempt for them both’, reflects Toomey, whose own attempts at writing novels are placed between them. Toomey’s novel A Way Back to Eden is presented as groundbreaking in its portrayal of homosexuality but full of absurd and overblown metaphors, and dismissed by Lewis out of hand.

Joyce is only interested in a single word that Toomey says: “What, asked Joyce, do you call an earwig in your part of the world? ‘An eeriwiggle,’ I said. ‘Eire wiggle,’ Joyce said in blind smoking joy. ‘Write it down on this cigarette packet. You err and then you wiggle out of it. Och,’ he said, ‘I was never much good at continuing stories.’”

The earwig reference is to the Earwicker family at the heart of Finnegans Wake: the outrageous suggestion is that Toomey has inadvertently provided the inspiration for Joyce’s masterpiece. Yet in the world Burgess has created for us in Earthly Powers the possibility is entirely plausible.

Much later in the novel there is some discussion of what it means to incorporate real writers into fiction. This discussion is presented as taking place inside a novel that Toomey himself is writing:

I went to my study and, sighing, numbered a new sheet of foolscap (140), recalled some of my characters from their brief sleep and set them talking. They started talking, to my surprise, about the novel which contained them, rather like one of those cartoon films in which anthropomorphic animals get out of the frame and start abusing their creator.

‘A novelist friend of mine: Diana Cartwright said, ‘affirmed that a satisfactory novel should be a self-evident sham to which the reader could regulate at will their degree of incredulity.’

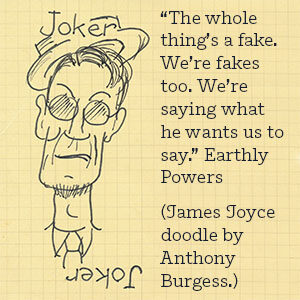

‘A sham, eh?’ Walter Dunnett said. ‘Even when there are verifiable historical personages in it? Like Havelock Ellis and Percy Wyndham Lewis and Jimmy Joyce?’

‘They’re not the same as what they would be in real life. The whole thing’s a fake. We’re fakes too. We’re saying what he wants us to say. You see that Dégas over there – he could turn it into a Monet at the stroke of a pen. He could make me die now of a heart attack.’

I nearly wrote: She died at once of cardiac arrest.

This sudden folding of fictions into other fictions is deeply troubling to Toomey, who stumbles shakily around his office before crumpling the sheet he had started and ‘[forcing] the characters back into total servitude to my will. Slaves, sort of, with only the illusion of freedom. Like all of us. The novel form was no sham.’ Burgess himself perhaps has no such anxieties. Earthly Powers is a sham, of course, but it is also a bravura performance: a fiction that draws attention to its fictional nature and that values its own inauthenticity, a series of illusions that it exults in undermining.

James Joyce himself does not reappear in the novel — although there is a climactic performance of Burgess’s musical version of Ulysses, Blooms of Dublin, with quotations from the libretto and descriptions of the extravagant, impossible staging. One of the characters goes so far as to baldly state that ‘it can’t be done’; but in Earthly Powers it can, and ‘there is applause. Much applause.’