Object of the Week: Burgess and Lynne’s Limericks

-

Graham Foster

- 2nd May 2017

-

category

- Object of the Week

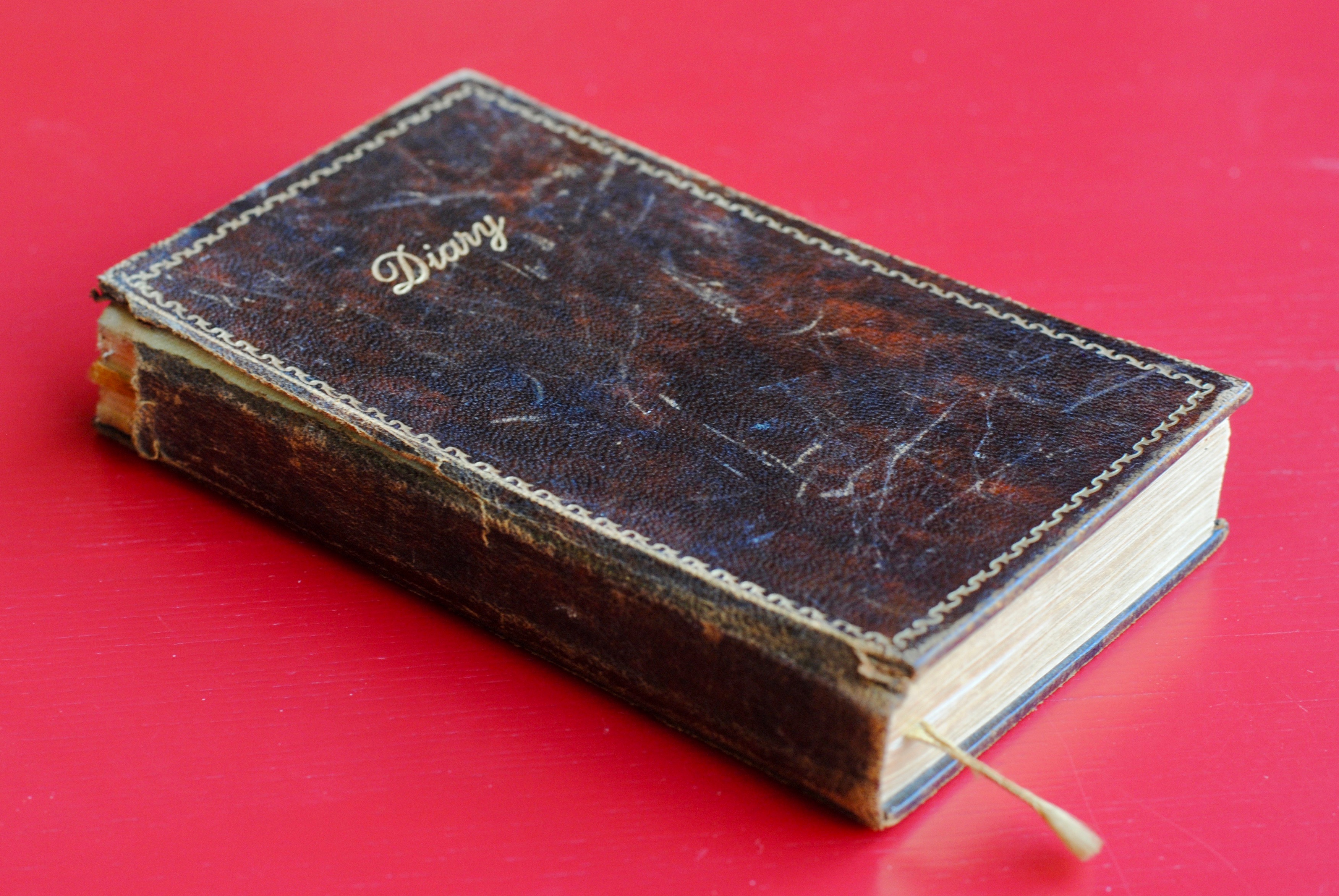

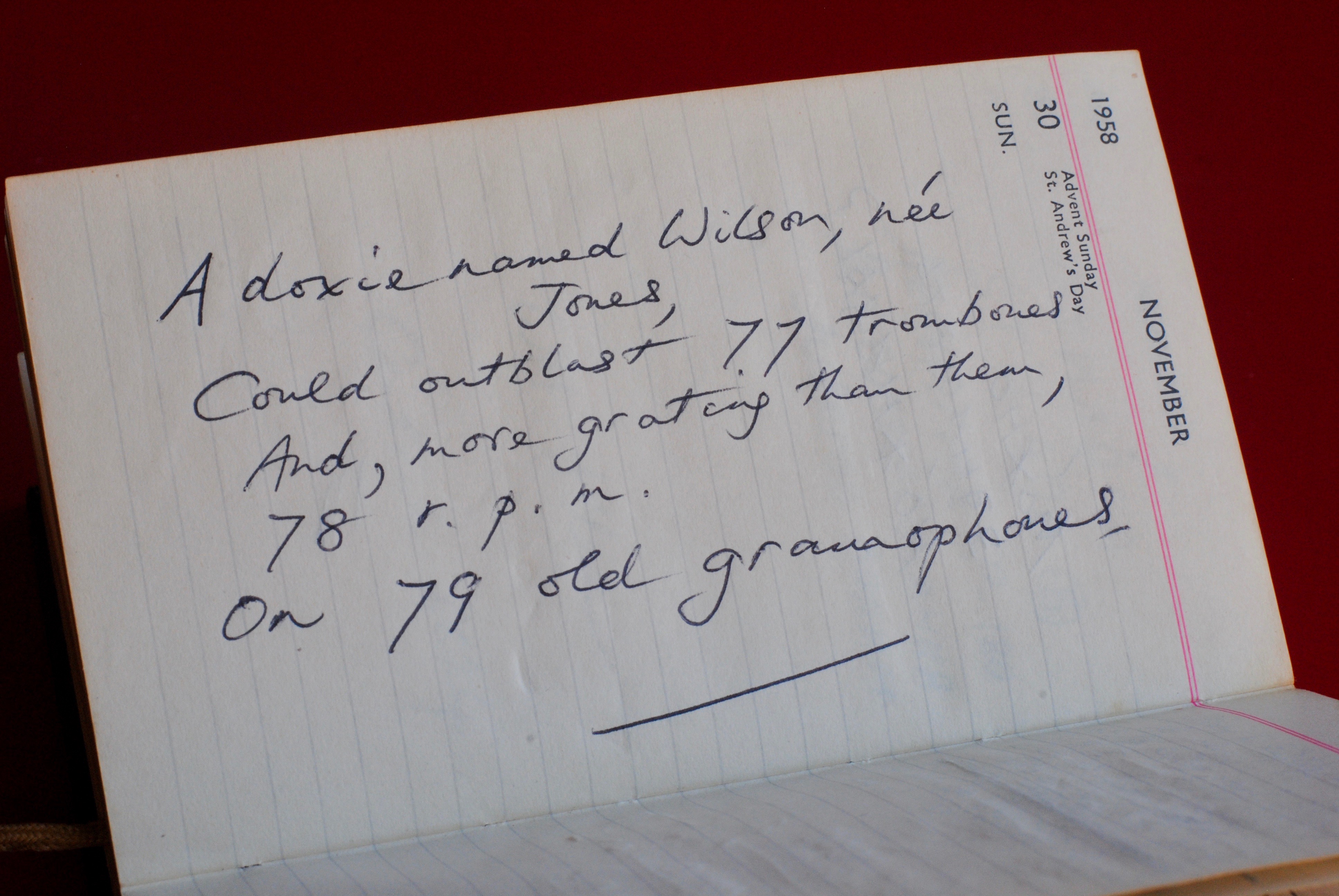

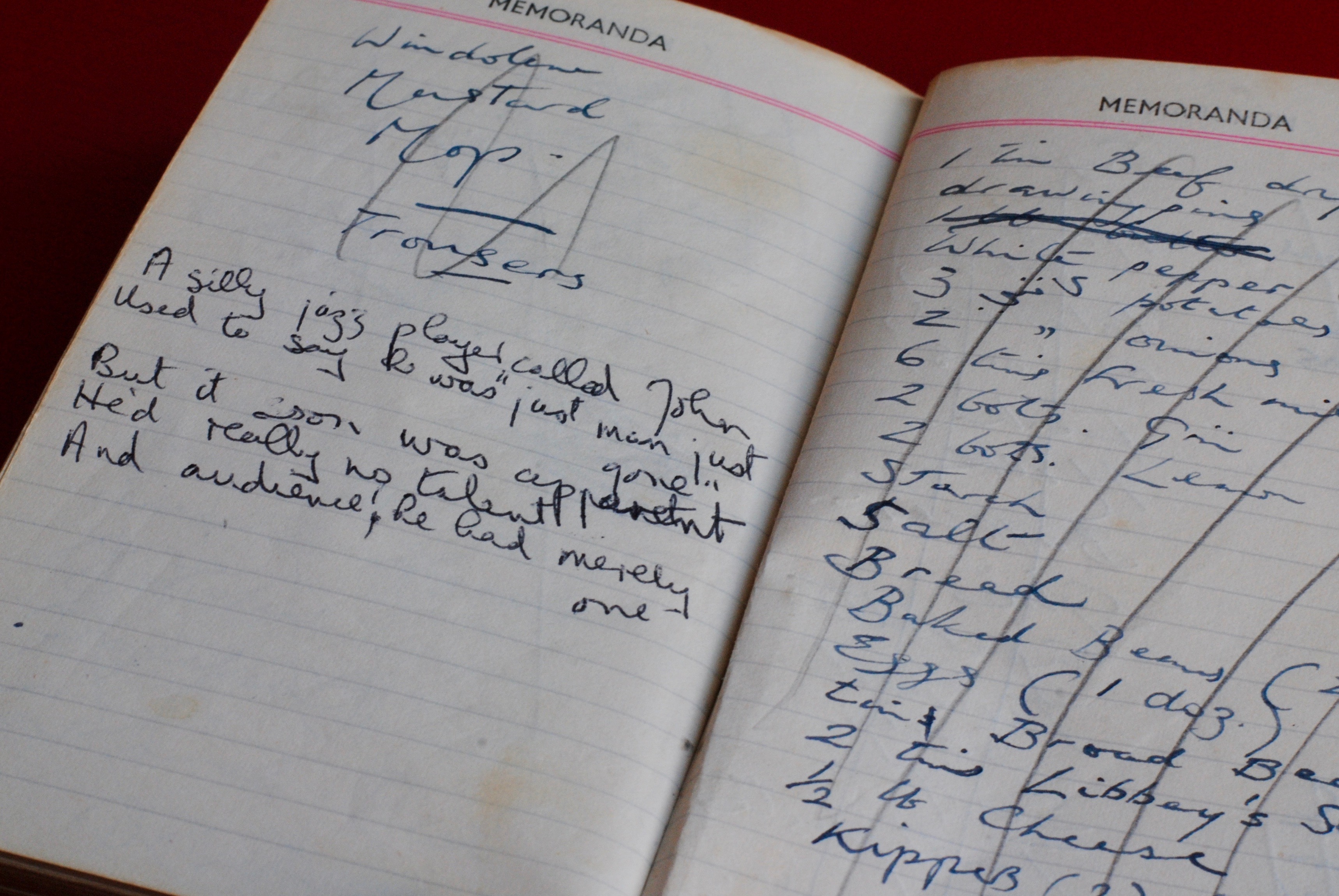

The Burgess Foundation archive contains several diaries kept by Burgess between 1952 and 1974. These have a combination of personal entries, shopping lists, notes towards the writing of novels and records of finances. At the end of the diary for 1958, there are a series of limericks written by Burgess and his wife Lynne in which they take to insulting each other in creative and playful ways. These begin on the page marked Sunday 30 November 1958 with Burgess’s limerick to Lynne:

The Burgess Foundation archive contains several diaries kept by Burgess between 1952 and 1974. These have a combination of personal entries, shopping lists, notes towards the writing of novels and records of finances. At the end of the diary for 1958, there are a series of limericks written by Burgess and his wife Lynne in which they take to insulting each other in creative and playful ways. These begin on the page marked Sunday 30 November 1958 with Burgess’s limerick to Lynne:

A doxie named Wilson, née Jones,

Could outblast 77 trombones.

And, more grating than them, 78 r.p.m.

On 79 old gramophones.

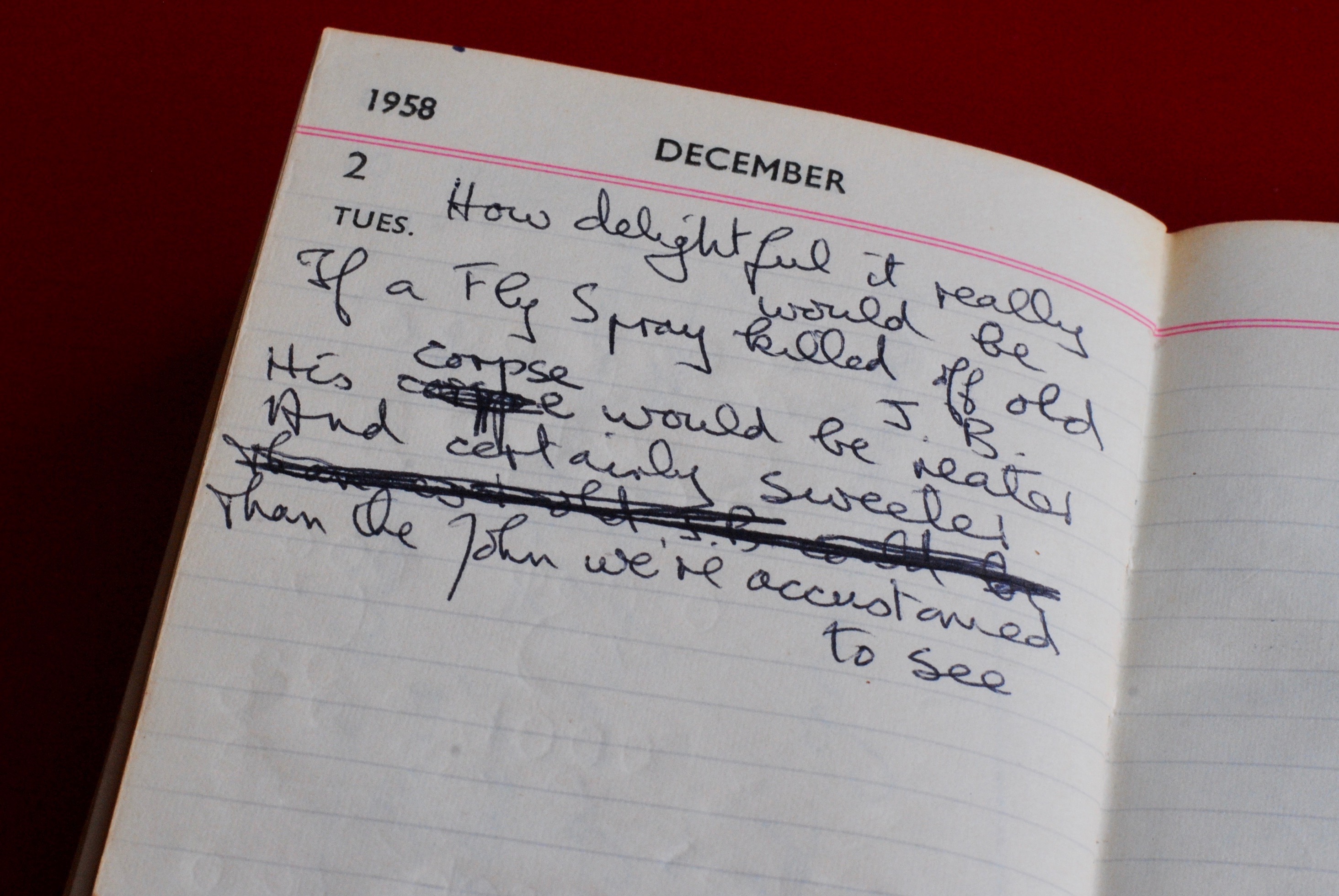

Lynne responds on 2 December:

How delightful it really would be

If a fly spray killed off old J.B.

His corpse would be neater

And certainly sweeter

Than the John we’re accustomed to see.

Burgess’s love of the limerick form is apparent through much of his work. In The End of the World News, he quotes a verse by the composer Peter Warlock:

The young things who frequent movie palaces

Know nothing of psychoanalysis.

But Herr Doktor Freud

Is not really annoyed.

Let them cling to their long-standing fallacies.

He also reviewed anthologies of limericks, writing about The Penguin Book of Limericks: ‘This book is a fine tribute to all those of us who like brevity as the soul of obscenity, find rhyme witty in itself and would love to join the great limerickizing anonymous. I, naturally, blush at finding myself here.’

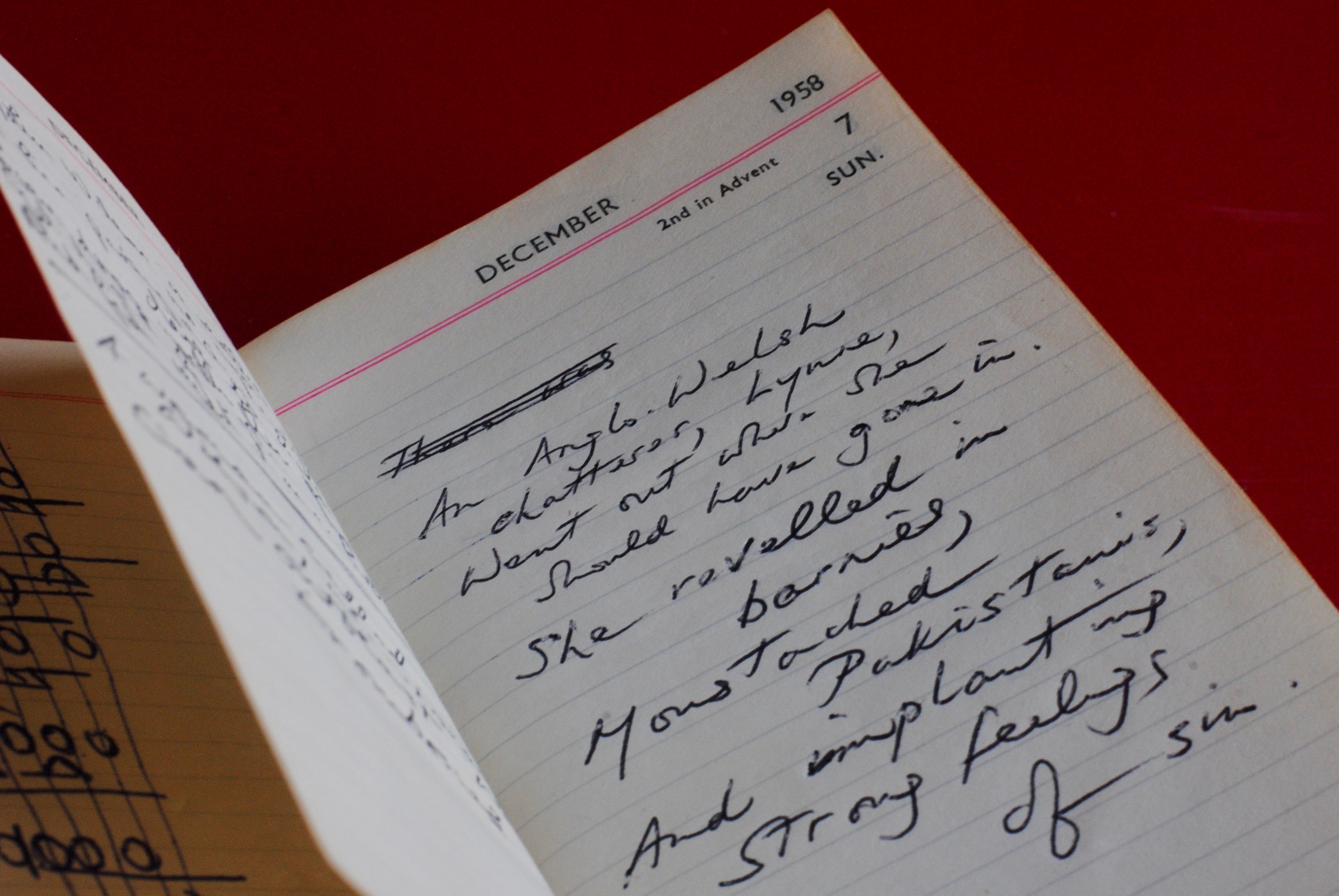

Much of Burgess’s work reveals his bawdy sense of humour, from the Shakespearean romp Nothing Like the Sun to his verse novel Byrne, which is written with a Byronic spirit. Yet it would be a mistake to view this aspect of Burgess’s work as frivolous. He was part of a generation who lived through the censorship of authors such as James Joyce, and experienced the Lady Chatterley Trial in 1960. Burgess was a fierce champion of the need for literature to represent all forms of human experience, not just the genteel or polite. He defended Hubert Selby Jr’s Last Exit to Brooklyn (1964) against charges of obscenity, writing, ‘How this honest and terrible book could ever be regarded obscene (that is, designed for depravity and corruption) is one of the small mysteries of the decade’.

The diaries in the Burgess Foundation archive also show that Burgess was impressed by the poetry of John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester. He has copied out several of Wilmot’s scandalous verses in the diary for 1952. At the time Burgess was living in Adderbury, Oxfordshire, where Rochester lived in the seventeenth century. Later in his life, Burgess began translating the bawdy and blasphemous Roman poetry of Giuseppe Gioachino Belli into the Lancashire dialect of his youth. As a young man, Burgess grew up in a very male world. He was raised by his father, through whom he was introduced to the public houses of Manchester, and he experienced a segregated education before joining the army in 1940. Throughout this time, Burgess would have heard all sorts of expressions and different sorts of language. Indeed, he credits his experiences in the army as vital to his education in obscenity when he heard an engineer curse the vehicle he was working on: ‘Fuck it, the fucking fucker’s fucking fucked.’

In many ways, Burgess’s first marriage was a troubled period, but these limericks show that Burgess’s relationship with Lynne had a different side to it, one that shows great affection and a delight in shared jokes. This affection is indicated in Little Wilson and Big God, when Burgess writes, ‘Marriage is built on a common past, a closed culture, a community of myths. A shared line of poetry can evoke a whole swathe of experience. The conversation of a married couple is built out of codes.’