Object of the Week: Burgess Reading A Christmas Carol

-

Graham Foster

- 19th December 2017

-

category

- Object of the Week

The audio collections at the Burgess Foundation contain several recordings of Burgess reading his own work, extracts from his novels, or lectures recorded by Liana. It is unusual to find him reading the work of other writers. A recent discovery is a tape of Burgess reading A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens, in which he accompanies the story with incidental music from his own record collection. The reason for this recording is not known, though there are other tapes in the collection of Burgess reading to his son, Paolo Andrea. It is possible that this recording is associated with Burgess’s involvement in marking the centenary of Dickens’s death in 1970. He attended a lavish Dickensian banquet at Yorke University in Toronto at which he gave a talk on Dickens as playwright and actor, and Paolo Andrea ‘in the role of Tiny Tim, was raised to the table on four telephone directories’.

Burgess’s talk for this occasion was not recorded, but the typescript is in the archive at the Burgess Foundation. In the talk, Burgess draws Dickens into his own experience by attempting to prove that the city of Manchester was integral to Dickens’s development as a writer. A Christmas Carol, Burgess says, found its genesis in Manchester, and the model for Scrooge could be found in ‘the brothers Grant, who worked in Cheeryble House on Cannon Street’. In Little Wilson and Big God, Burgess claims that his great-grandfather met Dickens in Manchester after one of the author’s readings.

Burgess wrote about Dickens throughout his career, with some of the earliest writing appearing in the 1958 textbook English Literature. In this book, he begins his summary of Dickens’s work unexpectedly: with some harsh criticism. ‘Everybody is aware of the faults of Dickens – his inability to construct a convincing plot, his clumsy and sometimes ungrammatical prose, his sentimentality, his lack of real characters in the Shakespearean sense’. Burgess eventually concludes that ‘The secret of his popularity lies in an immense vitality, comparable to Shakespeare’s, which swirls round his creations and creates a special Dickensian world’.

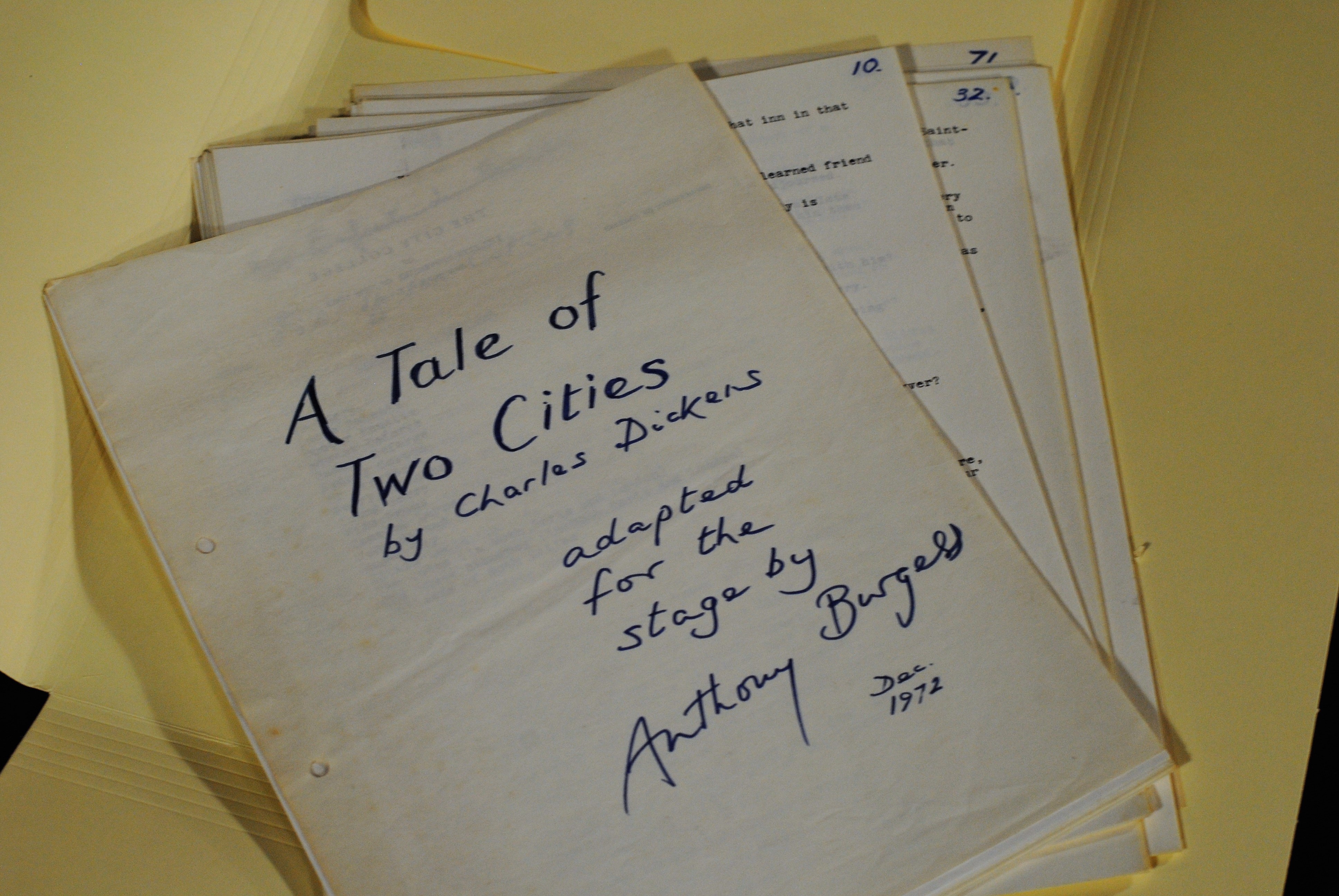

As Burgess’s career progressed, so too did his engagement with this ‘Dickensian world’. In 1972 he was commissioned by the Tyrone Guthrie Theater in Minnesota to adapt A Tale of Two Cities for the stage. This play was never performed, but a draft typescript is in the archive at the Burgess Foundation. Burgess was also approached by a Canadian television company to dramatize and complete The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Although he agreed to undertake this work, there is no existing typescript and it was never broadcast.

It is possible that Burgess saw Dickens as a kindred spirit. In his book They Wrote in English (1979), he writes: ‘The son of a government clerk who was imprisoned for debt, Dickens spent much of his life redeeming that shame and his own childhood poverty. Precocious, though lacking the formal education of most of his contemporaries […] but, with the Pickwick Papers, shot into fame and soon to wealth.’ As with his writing on Shakespeare, Burgess highlights the aspects of Dickens’s biography (such as his opposition to the educated literary establishment in London, or his childhood poverty and subsequent wealth) which reflect his own.

In comparison to James Joyce and Shakespeare, Burgess did not frequently talk about Dickens as an influence on his own work, yet these archival objects and other writings show that Burgess spent a great deal of time attempting to understand his work.