Object of the Week: Burgess Reading Gerard Manley Hopkins

-

Graham Foster

- 27th September 2017

-

category

- Object of the Week

This recording of Anthony Burgess reading Gerard Manley Hopkins’s poem ‘Pied Beauty’ is part of Burgess’s private audio collection. It was originally part of a larger recording intended to accompany Burgess’s book They Wrote In English (1979), written for Italian student of English Literature. The recording fell out of circulation shortly after it was produced.

Burgess had a long relationship with the work of Gerard Manley Hopkins. He claimed to have read Hopkins on a ferry back from a school trip to France in 1930. On this same trip, he read James Joyce’s Ulysses for the first time, and, to commemorate the centenary of Hopkins’s death in 1989, he wrote, ‘I still cannot read Hopkins without the sensation of daring proper, at that time, to reading Ulysses.’ That Hopkins is entwined in this way with one of Burgess’s biggest influences shows how important the poet was to his creative development.

The first indication of Hopkins’s influence on Burgess can be seen in his school magazine, the Electron. In 1934 he contributed a poem titled ‘Jack Hopkins’, complete with Hopkinsian invented words and the poet’s influence on Burgess’s developing love of language:

Whether windowed a greycold welkin or a dawn that mounts and breaks

In a roseflush wave each day arises this working man,

Heavy maybe but never for a thwarted life’s plan

Seen shaped to the pounding day: for the day’s round he awakes.

He shakes sleep away. Day warms. He leaves and takes

A snap of suller cheese, hunked bread, a brew for his can,

And thrives in the air, strives, spits, swears. His breastcares span

But Saturday’s care or bet. Naught deeper rankles or aches.

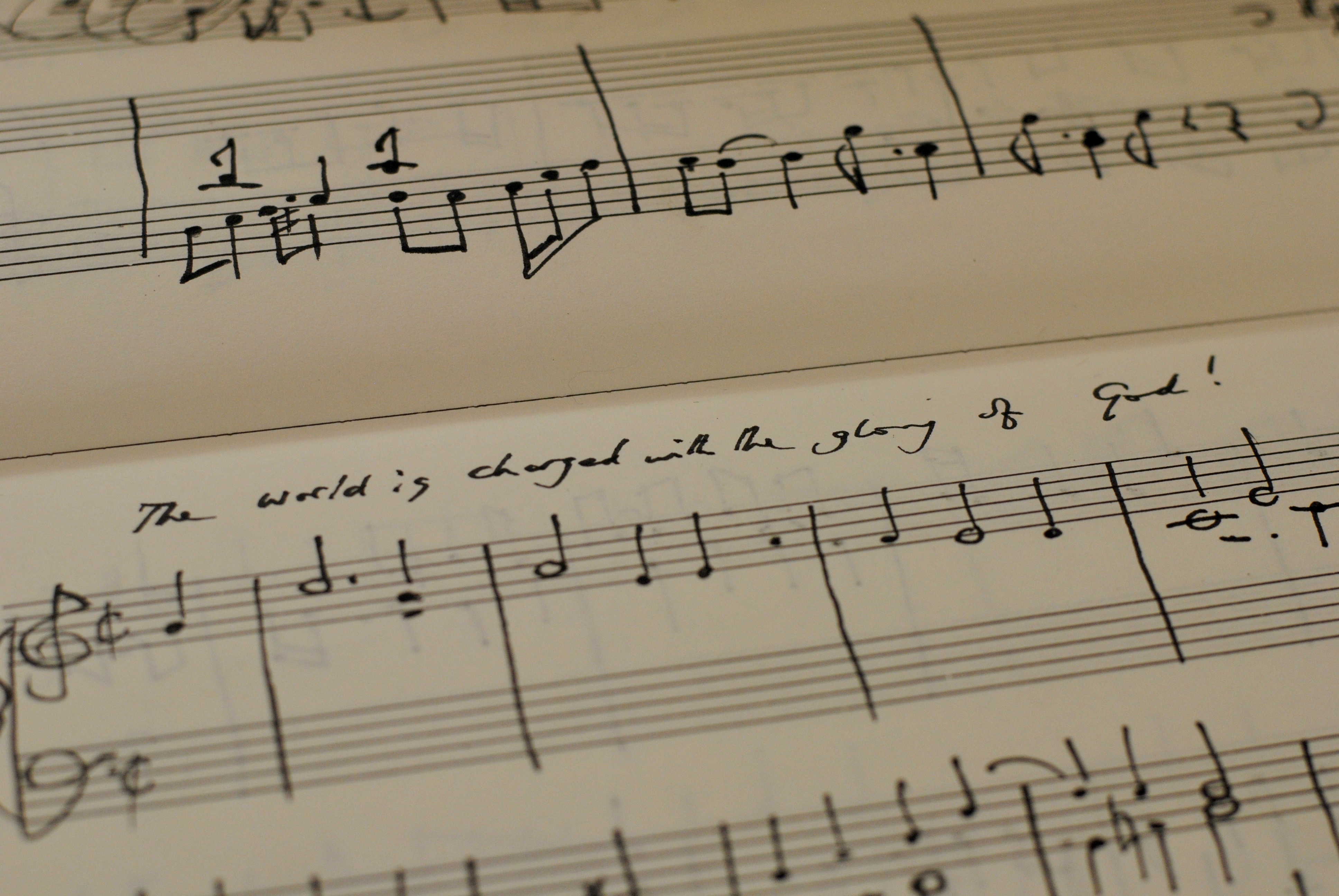

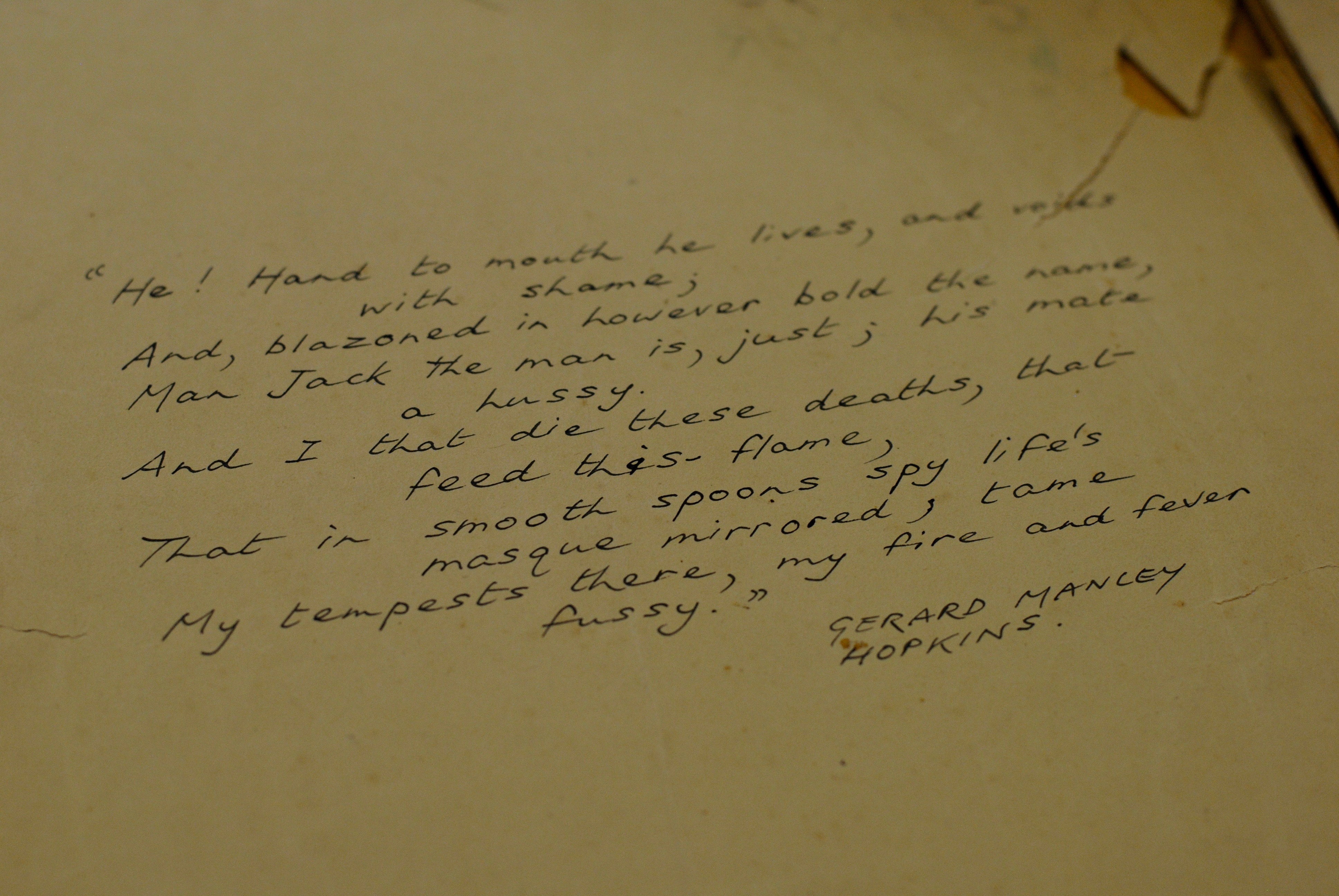

It is clear through other archival objects that Hopkins’s influence remained with Burgess through his experiences during the Second World War. On the manuscript of his earliest surviving piece of musical composition, Sonata for Violoncello and Piano in G Major, there is a stanza of Hopkins’s verse. The musical score, dated August 1945 and written when Burgess was serving in Gibraltar, begins with a fragment of ‘The shepherd’s brow, fronting forked lightning, owns’ which reads:

He! Hand to mouth he lives, and voids with shame;

And, blazoned in however bold the name,

Man Jack the man is, just; his mate a hussy.

And I that die these deaths, that feed this flame,

That in smooth spoons spy life’s masque mirrored, tame

My tempests there, my fire and fever fussy.

Hopkins’s influence can also be seen in Burgess’s fiction. Nadsat, Burgess’s invented teen-speak from A Clockwork Orange, is made from many sources, including Russian loanwords, Elizabethan English, and Cockney rhyming slang, but more covert are the literary influences. For example, when Alex laments his fatigue, he states he is ‘shagged and fagged and fashed’ which is derived from Hopkins’s dramatic poem ‘The Leaden Echo and the Golden Echo’: ‘Oh why are we so haggard at the heart, so care-coiled, care-killed, so fagged, so fashed, so cogged, so cumbered.’

Hopkins’s long poem The Wreck of the Deutschland appears in the third Enderby novel, The Clockwork Testament (1974), as the eponymous poet adapts it into a film script. The resulting film is brutal and controversial, laced with sex and violence, bearing little resemblance to Hopkins’s poem or Enderby’s script. This mirrors the strife that the film version of A Clockwork Orange caused, and from which Burgess had to defend both his novel and the film.

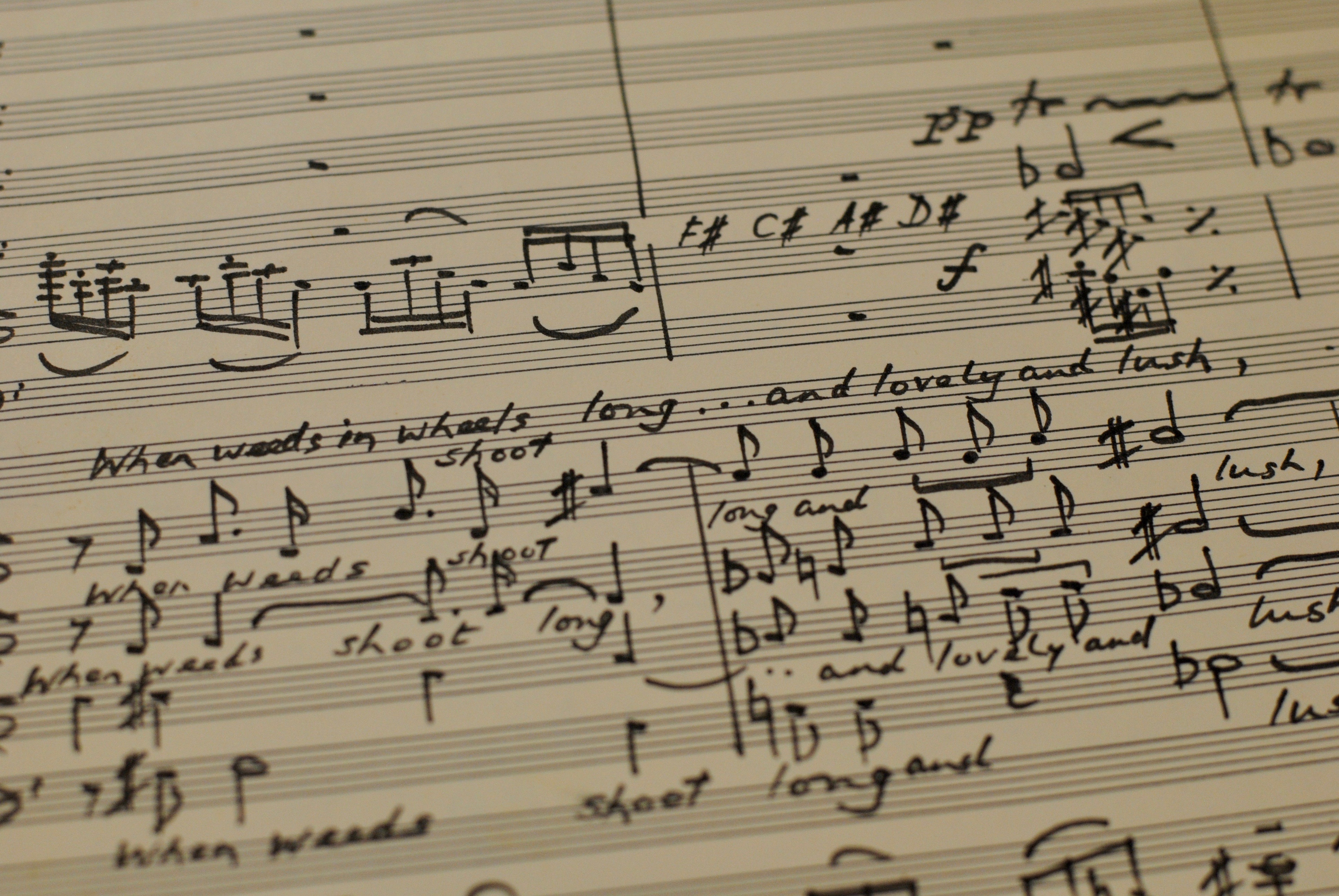

The Wreck of the Deutschland, in particular, caught Burgess’s creative attention. In 1982, he set the entire poem to music. Remembering this task in his autobiography, he writes:

‘I put together my thoughts on music and literature in a brief book, then fixed myself up at an outdoor café table with ballpoints and scoring paper and set Hopkins’s “The Wreck of the Deutschland” for baritone soloist, chorus, and large orchestra. It could not, of course, be done, but I had to prove it to myself. I could not compose my own rhythms; I had to follow Hopkins’s, and his sprungness got lost in the choral counterpoint.’

Despite his doubts about the project’s success, the manuscript was completed and runs to 138 pages. This complete setting of the poem has never been performed. Even though Burgess seems to have been unhappy with his attempt, he states that ‘Music is multiguous, since it is capable of many interpretations. Music, one might say, is Hopkinsian.’

Though much has been written about Burgess’s engagement with other literary influences, such as Shakespeare, Joyce and Eliot, Hopkins remains comparatively unexplored. Hopkins’s work is part of the foundation of Burgess’s preoccupation with language, and it has a large influence of the development of Burgess’s idiosyncratic fictional voice. When Burgess was asked by the Sunday Times to select his seven wonders of the world, one of his choices was the sonnet form, and he used Hopkins’s ‘Spelt from Sybil’s Leaves’ as a perfect example.

Speaking of his love of Hopkins, Burgess wrote in 1989: ‘He was ready to teach the world the idiom of ecstasy, but we reserve ecstasy for the latest state-of-the-art acquisition. We live in an age of dilution. Hopkins brews the powerful liquor of faith – in God, also in language.’