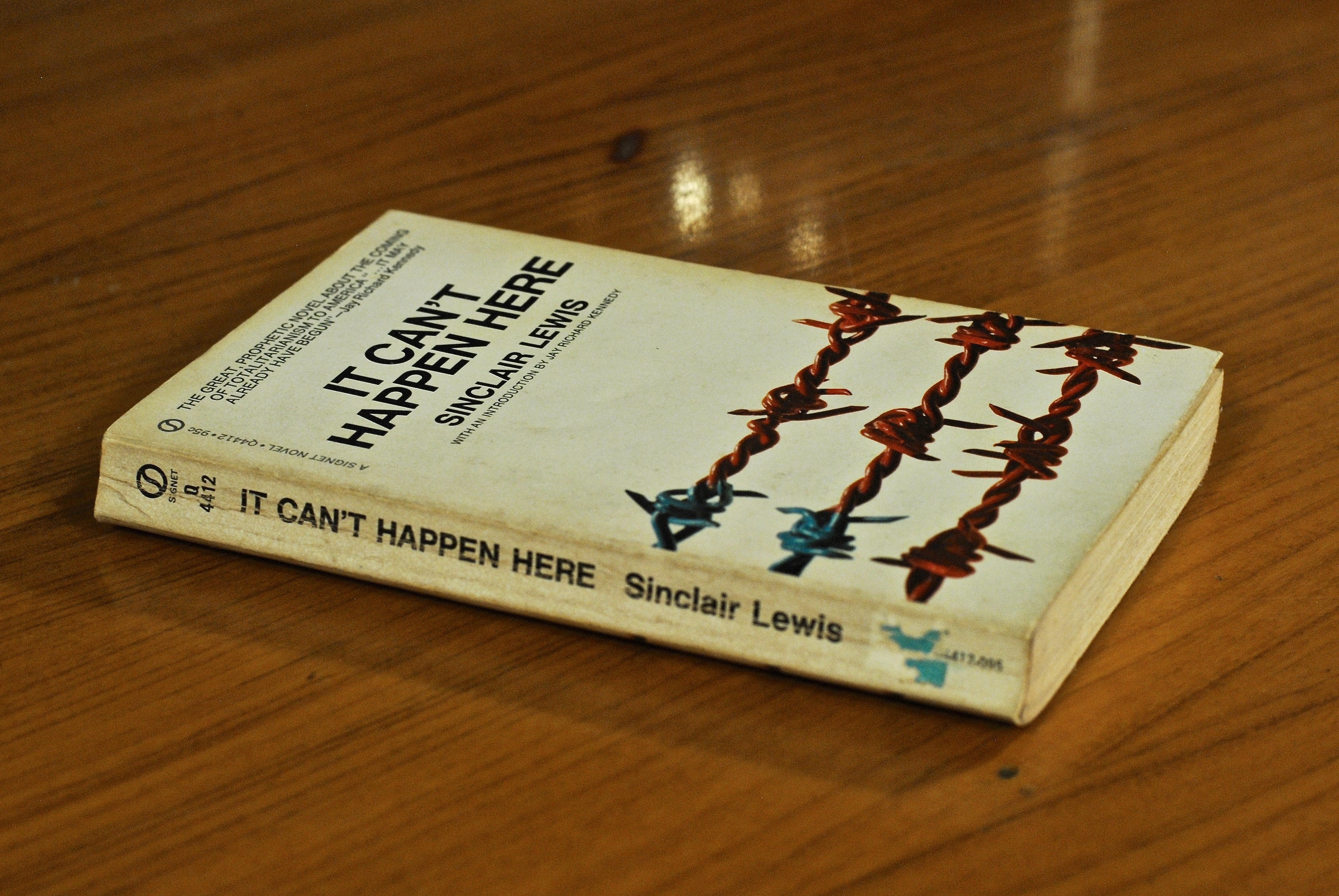

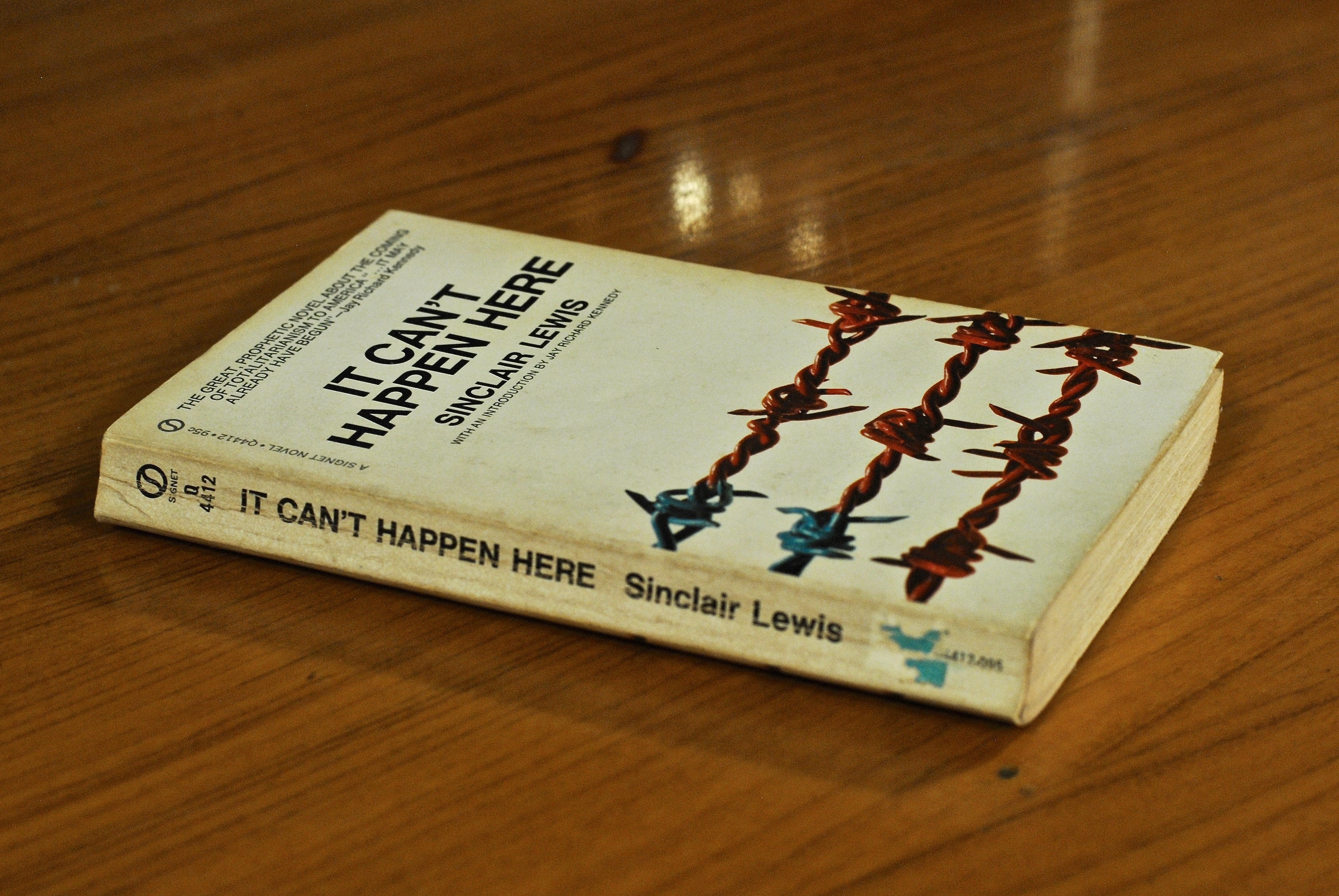

Burgess’s inscribed copy of Sinclair Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here (1935) displays the tag-line ‘The Ultimate Triumph of the Silent Majority’, something that indicates the novel’s relevance today. Burgess says in The Novel Now (1967), the book proves that ‘America can have its own bad dreams’, with antagonist Senator ‘Buzz’ Windrip securing presidential victory, dissolving Congress, banning information, and promoting of ‘Corporatism’.

Burgess originally read the novel shortly after publication, but this copy dates from 1970, showing that Burgess returned to it again later in life.

Burgess’s fascination with dystopian fiction lasted his whole life, but his writings about possible political futures stretch further than his novels A Clockwork Orange (1962), The Wanting Seed (1962), and 1985 (1978). Writing about the possibilities of the year 2020, he says: ‘The English Language, which used to unify, is now in the service of division, and I think, by 2020, we shall have gathered in the full harvest of divisive growth’. He also considered American politics in a 1992 essay in the London Evening Standard, focussing on one of the presidential candidates, a ‘citizen whose main claim to notice is his hard-earned billions’, and whose ‘popularity rests on the dissatisfaction, predominantly in the American middle class, with both the Democratic and Republican policies’. This candidate, Ross Perot, won 18.9% of the popular vote without being allied to any political party. He ultimately lost to Bill Clinton.

Burgess’s warning against populism derives not only from observation of the real world. It is also a reaction to much of the dystopian fiction he was reading throughout his life, not least Sinclair Lewis’s novel, which itself articulates a corrupt administration founded on a populist platform. Its depiction of the President’s calls for peace through defence, and his decrying of irresponsible news reporting, were intended as a hard warning for a complacent population, but Burgess saw the novel’s rhetoric come to life in the political world around him.

For more on Burgess’s engagement with dystopian fiction, click here.