Object of the Week: Burgess’s Copy of Collected Poems by T.S. Eliot

-

Graham Foster

- 27th March 2017

-

category

- Object of the Week

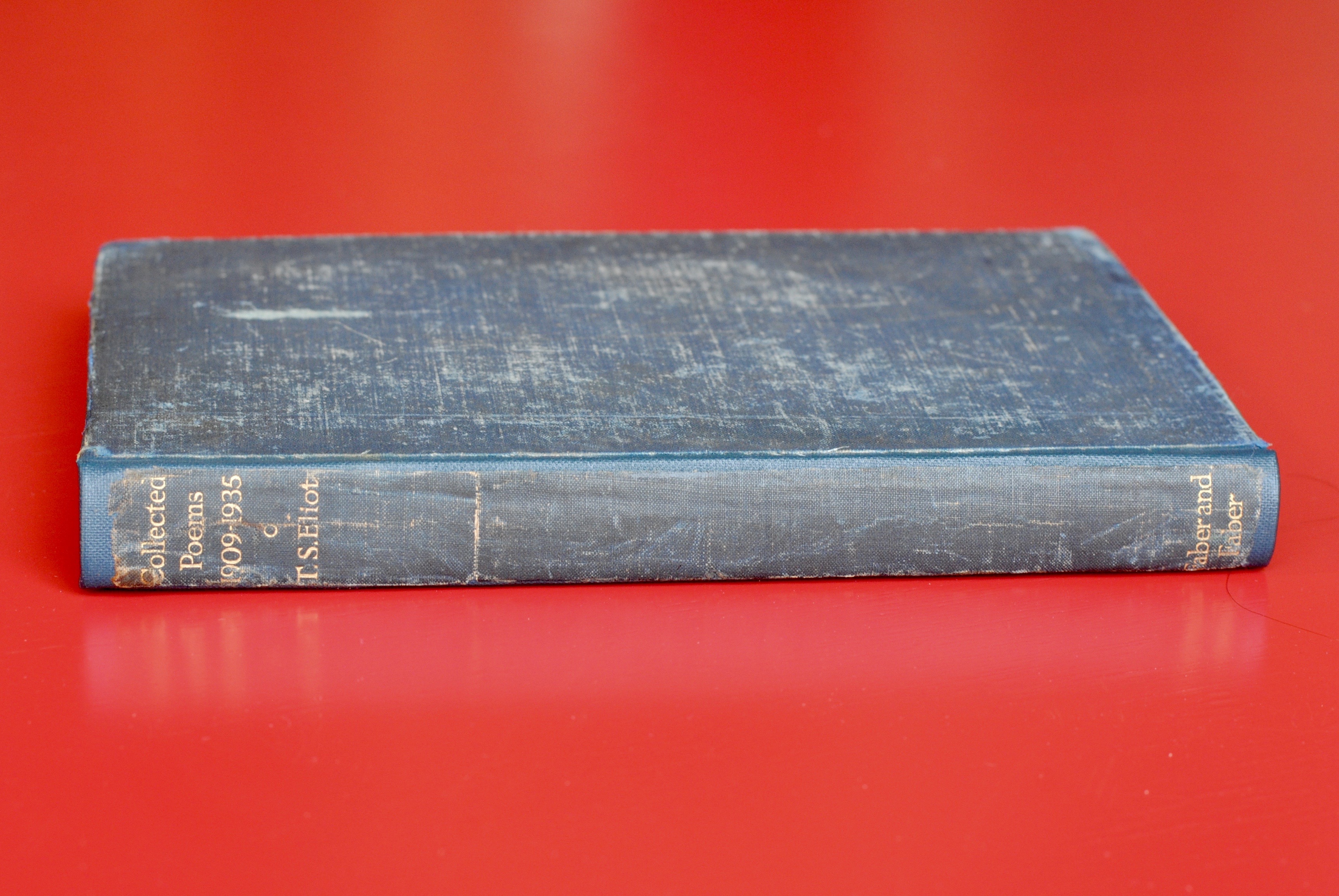

Anthony Burgess bought this copy of Collected Poems 1909-35 by T.S. Eliot in 1936 on a trip to London with his father. He recalls the occasion in Little Wilson and Big God (1987): ‘I took the train from Euston and read through T.S. Eliot’s Collected Poems 1909-35, which I had bought in Charing Cross Road. The entire volume failed to last the journey. Eliot had not written much from 1909 on.’

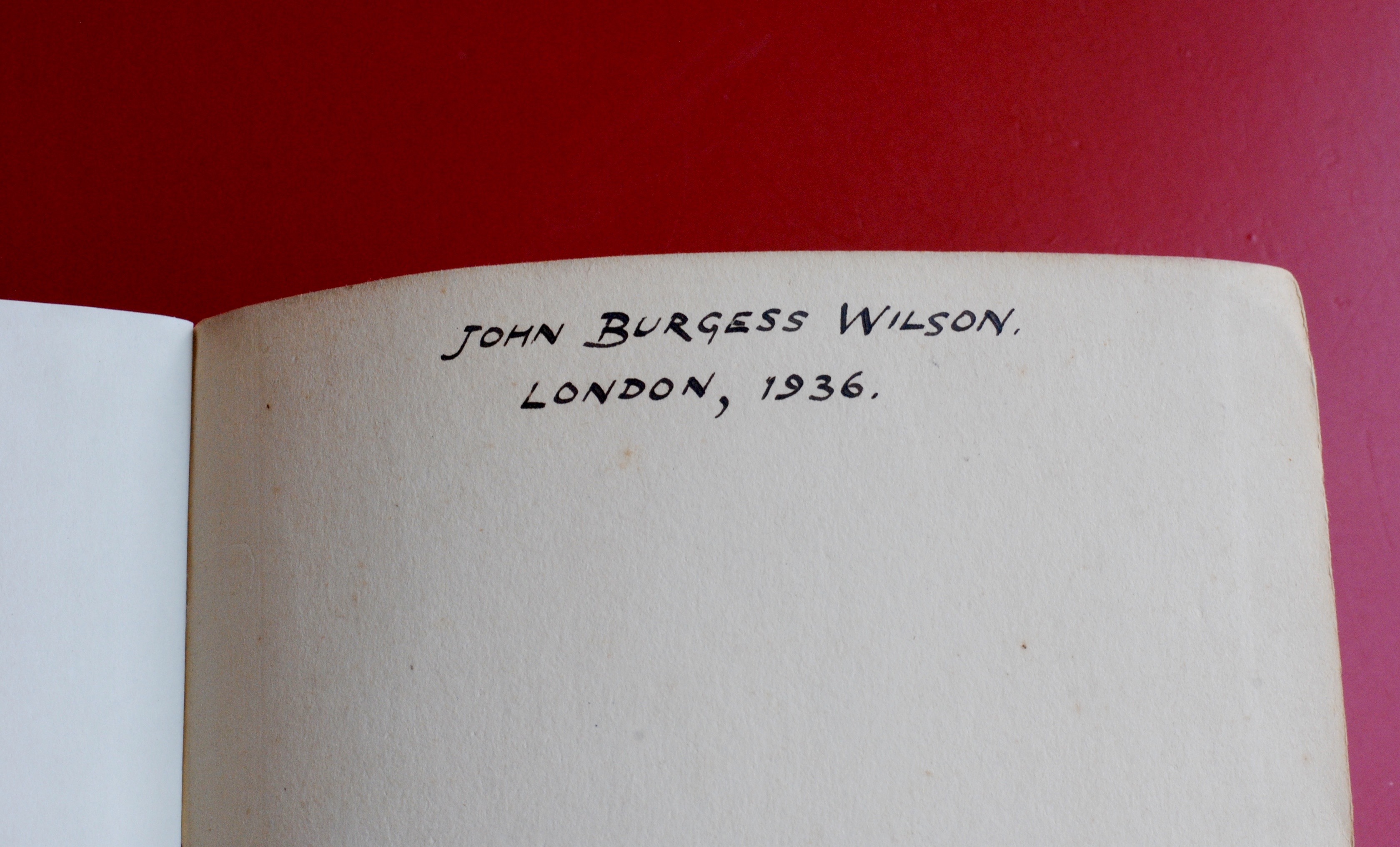

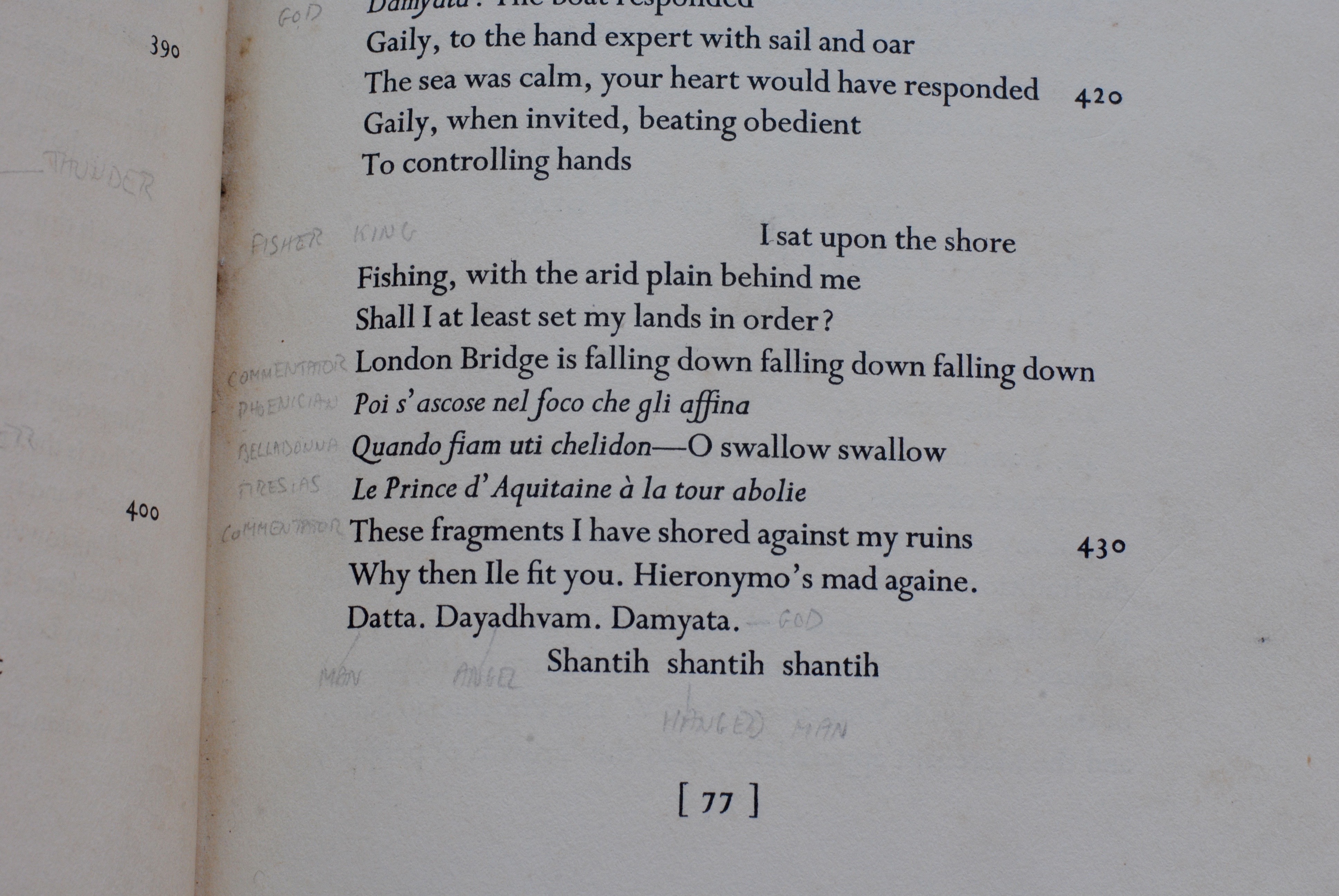

Inside, on the fly-leaf, Burgess has written his name, John Burgess Wilson, and the date when he purchased the book, but perhaps more interestingly there are pencil annotations throughout The Waste Land. These are not in Burgess’s hand. The annotations seem to indicate the division of the poem into parts, for a dramatic reading. Burgess reports that he was involved in a dramatization of The Waste Land at Manchester University, and he was also involved in amateur dramatics during his time in Bamber Bridge and Banbury in the 1940s and 1950s.

This dramatic reading was one of many creative responses to Eliot’s work. Burgess’s first attempt to set Eliot’s poetry to music took place on that train journey from London to Manchester in 1936: ‘I took music manuscript paper from my suitcase and sketched settings of the songs in Sweeney Agonistes.’ Three years later, when he was a student, Burgess set ‘Lines for an Old Man’, and in 1976 he set The Waste Land in its entirety as a ‘melodrama’ for narrator, soprano, flute, oboe, cello and piano.

Burgess’s interest in Eliot started at an early age. In Little Wilson and Big God he claims: ‘By the time I got to Manchester University, I understood The Waste Land pretty well. Without boasting, I can say that I knew the poem better than any of my English lecturers: they did not have it by heart, and I did.’

Burgess was quick to acknowledge the influence of Eliot on his early novels: ‘It was, I discovered myself when I first began to write seriously, hard to get the Eliotian voices out of my ears and my prose. It was so delightful to conjoin mock-pomposity with deliberate vulgarity, to throw in recondite literary allusions for ironic effects, to make statements conveying an authority somehow both professorial and parsonic, and yet, at the same time, tinged with self-mockery.’

The Waste Land appears in the first novel Burgess completed, A Vision of Battlements (published 1965, but written in 1952). Inspired by his wartime experiences, the novel tells the story of an instructor in the Army Educational Corps, stationed in Gibraltar. The Waste Land is quoted directly at various points in the text: roosters are seen ‘cocoricoing’ (recalling line 392 of the poem), the thunder speaks (line 399), and there is an allusion to Madame Sosostris reading Tarot cards (‘The wisest woman in Europe with a wicked pack of cards’, lines 45-6).

There are further allusions to The Waste Land in Time for a Tiger (1956). In one scene, Fenella Crabbe reads the entire poem to Nabby Adams, a drunk Colonial police sergeant, and Alladad Khan, his loyal colleague. Nabby Adams has some difficulties with the poem: ‘He’s got that wrong about the pack of cards, Mrs Crabbe. There isn’t no card called The Man With Three Staves. That card what he means is just an ordinary three, like as it may be the three of clubs.’ The same idea resurfaces in Earthly Powers (1980), in which Kenneth Toomey notes Eliot’s misuse of Tarot cards. In his autobiography, Burgess claims that he attempted to translate The Waste Land into Malay as he was living in Malaya, but the Foundation’s archive contains no evidence of this translation.

In an unpublished letter to an American academic friend, Burgess suggested that The Waste Land, for his generation, is ‘part of the furniture of the mind and comes up at all times — often irrelevantly. But I don’t think I’d ever structure a book or sequence of books on the poem — it’s the texture, the rhythm, that counts.’