Object of the Week: Burgess’s Copy of Dune

-

Graham Foster

- 6th June 2017

-

category

- Object of the Week

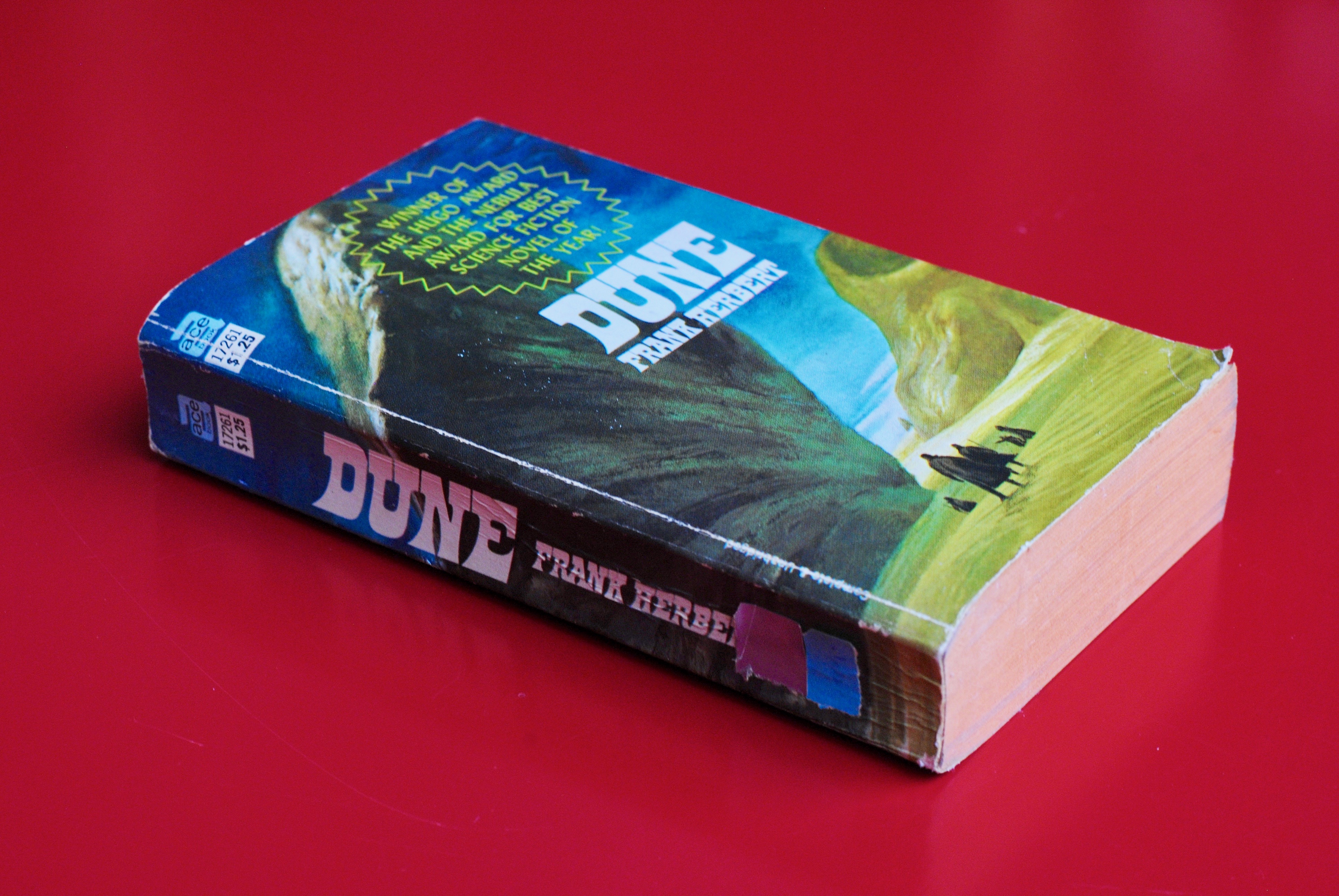

This copy of Frank Herbert’s Dune dates from 1966, when Anthony Burgess reviewed it for the Observer. He was impressed by the scope of the book and by the calibre of Herbert’s literary creation. The review displays a wide knowledge of science-fiction conventions.

Dune is set on Arrakis, a desert planet on which humans mine a mind-expanding spice called ‘melange’. Arrakis is home to giant sandworms, a native species which creates the spice as a by-product of their life-cycle. Arrakis is also troubled by a long feud between aristocratic families. It is in this setting that Herbert’s novel describes the rise of Paul Atreides, the heir to the House of Atreides, who has superhuman powers and is an expert military strategist.

In his review of Dune, Burgess writes: ‘The Duke of Atreides and Baron Harkonnen and the rest of them are genuine characters whose acts emotionally involve the reader’. Even so, the review is not completely complimentary. Burgess adds: ‘this devotion to detail and the evidence of immense literary care tend less to exalt the spirit than to depress it. What a waste, really. All this skill expended on mere fantasy’.

Elsewhere in his round-up review of new science fiction, Burgess is vocal about his dislike of the genre, claiming that ‘SF,’ as he calls it, is not written by artists, but by ‘a laboratory-man chain-smoking over a weekend typewriter.’ Of the cerebral value of science fiction, Burgess writes: ‘it resembles Jane Austen in its intellectual engagement. But Jane Austen at least created amiable characters and wrote very well’.

Elsewhere in his journalism, Burgess expanded on his reasons for disliking science fiction, claiming that it was often dull and poorly written. ‘You practice the genre if you have fancy but no imagination. Bizarre things matter more than such fictional staples as character, psychological probability and credible dialogue. There is usually an atmosphere of evasion of real-life issues, occasionally qualified by dutiful lip-service shibboleths about human freedom and embattled ecology. Content counts more than form.’

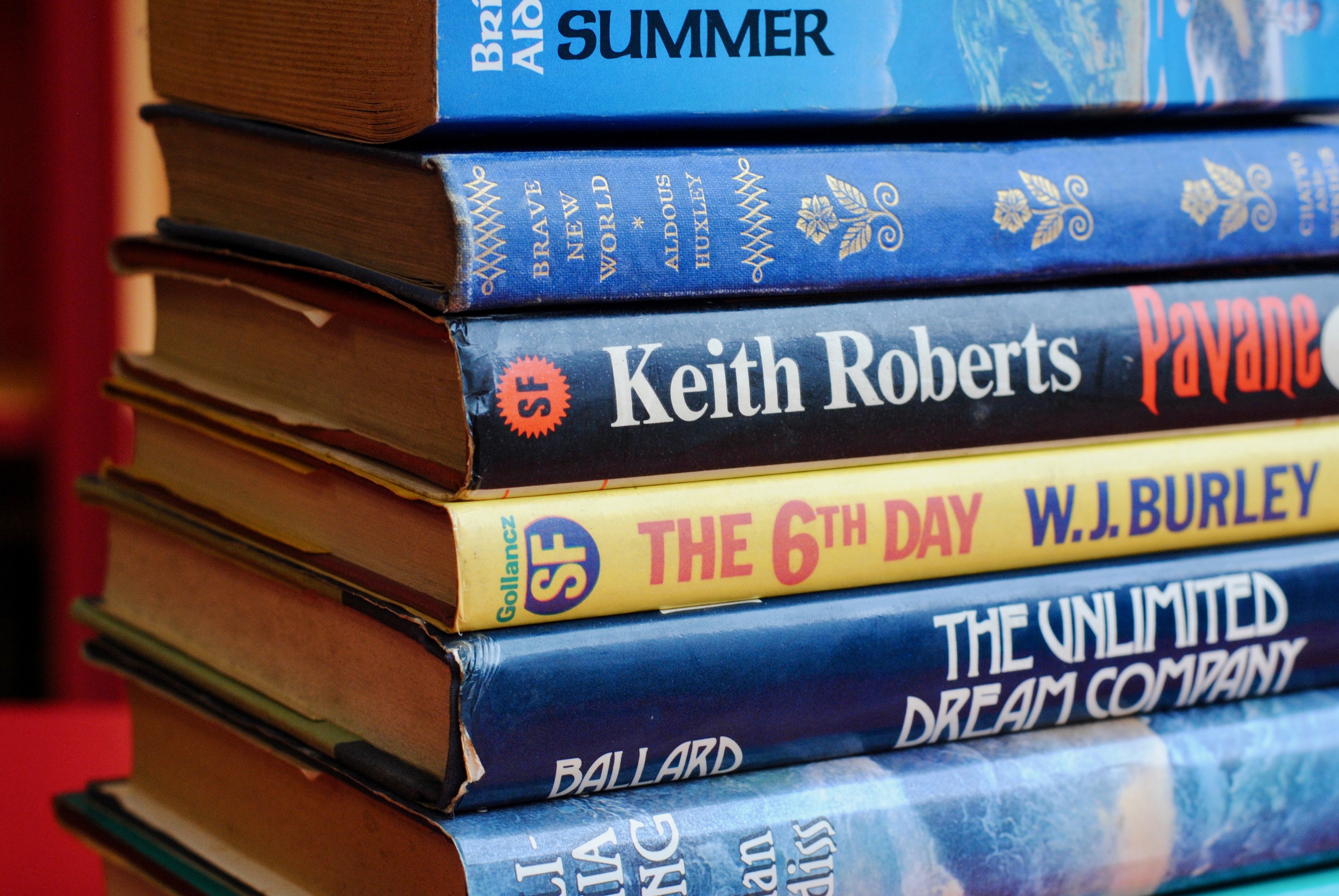

Despite these complaints, there is much evidence that Burgess read widely in the genre, and was, on occasion, willing to be impressed. In Ninety-Nine Novels: The Best in English Since 1939, Burgess selects novels by Brian Aldiss (a friend from the 1960s), J.G. Ballard, Russell Hoban, and L.P. Hartley (for his little-known novel, Facial Justice). He also identifies lesser-known works of speculative fiction, including Pavane by Keith Roberts, an counter-factual historical novel which portrays Catholic Britain in rebellion against the dominance of the Church. The book collection at the Burgess Foundation contains many other works of science fiction, including novels by H.G. Wells, Aldous Huxley, W.J. Burley and Margaret Atwood.

Although Burgess occasionally said disobliging things about genre fiction in his journalism, it is clear from his own novels that he thought writing science fiction was worthwhile. A Clockwork Orange, presents a dystopian world in which violent droogs rampage through urban streets, and The Wanting Seed shows a future Britain turned into a megalopolis by over-population. In The End of the World News Burgess tries his hand at apocalyptic fiction, and 1985 is a work of speculative fiction, written in response to George Orwell.

Burgess’s love of literature transcended generic boundaries, and his occasional denigration of science fiction does not tell the whole story about his lifelong engagement with the genre. His work as a critic often reveals surprises, and it shows that he was able to judge books on their merits, and not according to preconceptions about genre. Dune is a useful example. While it appears, on the surface, to be a novel at variance with Burgess’s interests, he is impressed, perhaps reluctantly, by Herbert’s sheer ability as a writer.